On the strange, semi-fictional quality of everything that happens in 2020.

For months now, the 2020 presidential election hasn’t felt entirely real to me.

The obvious reason is that the global outbreak of Covid-19 scrambled everything about the campaign to such a degree that it felt ever so slightly like an event happening in some other country entirely. “While this pandemic is going on, we’re going to also have an election?” I would catch myself thinking. “Really??”

But if I’m being honest, I was feeling this way back before the coronavirus came to dominate headlines. Remember the disastrous Iowa caucuses in early February, when there were huge problems with vote reporting, to the degree that essentially none of the candidates could claim momentum from them? Those, too, felt like an event happening in some other reality. Covid-19 contributed greatly to the distance I felt from this election, but it wasn’t the sole reason for it.

So it sort of made sense that the 2020 Democratic National Convention would be the first virtual convention, staged not in one central location but all over the country, a party spread across the nation in a fine smear, like jam on toast. Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were together, and a few important Democratic officials were in Milwaukee (where the convention was originally slated to be held). Barack Obama traveled to Philadelphia to deliver his speech.

But most of the events were broadcast from party members’ hometowns and living rooms, to the degree that I found myself a little fascinated with trying to examine the pattern on the Clintons’ couch. (I maintain that only grandparents would own a couch with that pattern, so it’s good that the Clintons are grandparents.) The whole endeavor had the intimacy of television, which even at its worst brings people right into your living room and invites them to plop down there, blended with the strangely distancing quality of videoconferencing software, which so often lags slightly behind reality.

For me, that weird blend of intimacy and lag contributed to a sense, all throughout the convention, that it wasn’t quite real. The virtual DNC felt either fictional or like a dry run for the real event. By the time Biden delivered his concluding speech officially accepting the party’s nomination for president, the whole hootenanny seemed, in rather surreal fashion, as if it were taking place inside a video game cutscene. Biden’s speech was the best I’ve ever seen him give, but the eerie vacuum he delivered it in made it seem like something selected from a menu of dialogue options.

Yet this fictional quality was also one of the primary strengths of the 2020 convention, which honestly might be my favorite political convention I’ve ever seen. It didn’t change my feelings about Biden, or Harris, or even Obama. But it did leave me feeling like I had watched some entertaining television.

The 2020 DNC featured bland politics, but it was frequently fun to watch

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21806673/kamalawide.png) PBS NewsHour/YouTube

PBS NewsHour/YouTubePerhaps the most surprising shot of the entire convention came late in Harris’s vice presidential nomination acceptance speech Wednesday night. Harris presented her remarks to a nearly empty convention center, and she kept pausing during moments where, normally, applause would drown her out. But without any devoted Democrats in attendance, her whole speech filtered out into an unforgiving room.

And then the camera pulled into a wide shot, looking at the stage from an angle. Seated throughout the empty space, observing proper social distancing, were a handful of reporters scattered about the echoing room. It was as striking a visual reminder of the highly strange circumstances of this convention as I could think of, and it spoke to just how awkward Harris’s speech could seem, because it reminded you there was no way her speech could avoid awkwardness.

Biden’s speech, delivered under similar circumstances, in a nearly empty convention center, played much better on television, and it speaks to a strength of this DNC: Its organizers and participants were willing to think on their feet. Biden didn’t pause for applause that wouldn’t come, and yet he parceled out his address in such a way that you could have emotional reactions at home should you want to. The camerawork kept a tight focus on Biden, compared to occasionally taking a wider view of Harris, as if trying to reestablish the former’s intimacy with the audience, while centering Harris as a relative newcomer on the global stage, stepping out into an unprecedented crisis.

Their speeches were also shorter than the typical convention speech. It was in keeping with the entirety of the event. Only Harris, Biden, and the two Obamas spoke for longer than 15 minutes, and even Bill Clinton, who has frequently delivered convention stemwinders, got only five minutes of screen time. (Rising party star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez got even less, in her speech seconding the nomination of Bernie Sanders.) It was an acknowledgment of a key difference of a virtual convention — without audience reactions to surf, a speaker like Clinton needed to stay sharp and to the point.

But I’m not sure that was a problem, either. Did we really need hour-long speeches? Barack and Michelle Obama are among the most effective political communicators of the TV era, and even they made efficient use of 20 minutes. Without a crowd present, their remarks were boiled down to their most effective and emotional points. They were tailored for TV, in other words.

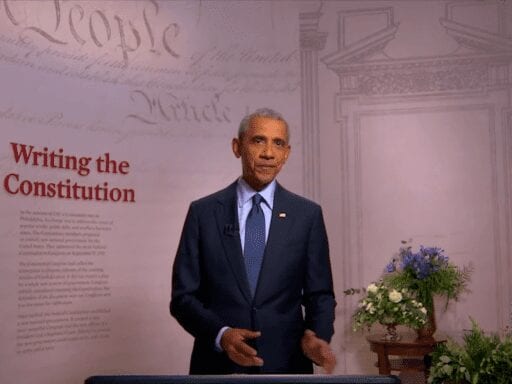

The convention also took chances in the way it staged speeches. Jill Biden’s speech opened as a walk-and-talk shot by what appeared to be a TV news camera. Barack Obama delivered his speech from the American Revolution Museum in Philadelphia, which lent the speech a gravitas a convention stage couldn’t hope to approach. Former Ohio Gov. John Kasich beamed in from a literal crossroads, and still other speechmakers (notably Long Beach, California, Mayor Robert Garcia) appeared from business places sitting quiet amid nationwide shutdowns.

And when in doubt, the convention aimed for the intimacy of reminding viewers that all of these party faithful had places to go home to. Getting to see Hillary Clinton or Michelle Obama appear from their homes created a vague sense that everybody “attending” the convention and everybody watching at home were in the same boat. Even the convention-goers gathered in Wilmington, Delaware, to “greet” Biden after his big speech were in their cars, a major political event reimagined as a drive-through graduation ceremony.

All of these choices combined to give the whole event a brisker pace. Each night’s programming ran for a little over two hours, and I never felt like any person or topic got short shrift or overstayed their welcome. It was just more entertaining to watch, while also accomplishing the core task of getting the Democratic Party faithful at least vaguely excited about Biden’s chances at winning the presidency.

But what made the DNC most successful was the meta-narrative baked into it.

The 2020 DNC wasn’t about averting catastrophe. It was about alleviating it.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21806691/1228133260.jpg.jpg) David Cliff/NurPhoto via Getty Images

David Cliff/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesThe biggest plan Biden outlined in his acceptance speech on Thursday had nothing to do with income inequality or systemic racism or climate change. He touched on all of those problems, but the one topic where he outlined a concrete approach was when he discussed what could be done about the coronavirus’s unchecked spread in the US.

Biden’s plan — lots of testing, lots of masks, lots of social distancing — isn’t any different from those of any of the countries that have controlled the spread of the disease. And yet just hearing it explained so clearly by an authority figure felt weirdly revolutionary, because, well, that authority has been in short supply of late. (I don’t know if you’ve noticed.)

“We’re going to do more testing to stop the spread of Covid-19” probably shouldn’t feel like the breath of fresh policy air that it does, but the very existence of the virtual convention underlined how necessary it is. All media is produced under certain constrictions and circumstances, and sometimes, it can make something artful of those constrictions and circumstances. This convention wasn’t art, but its value as television lay in how it was careful to rarely let the subtext (170,000 people have died) overwhelm the text (and let’s elect Joe Biden!).

That careful balance of subtext and text could have defeated the convention, but its light touch ensured that nothing got too bogged down, even in the endless strings of montages that took up the first hour of most evenings’ programming. At all times, the event relied on the power of images to convey a country that feels as if it’s careening downhill with nobody to stomp on the brakes — and to suggest, implicitly, that Joe Biden knows exactly how to stomp on the brakes.

I may not have left the 2020 DNC feeling any more excited about Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, but I did leave it feeling like there’s no reason any other political convention should go back to how they used to be. The DNC maybe wasn’t the rousing celebration of the party it would have been in other years, but it was pretty darn good television, which understood the horrors of the time required not something inspiring but something quiet, thoughtful, cautionary, and hopeful. We might be careening downhill, the message went, but the brakes are still functional. We just have to elect someone who knows how they’re supposed to work.

New goal: 25,000

In the spring, we launched a program asking readers for financial contributions to help keep Vox free for everyone, and last week, we set a goal of reaching 20,000 contributors. Well, you helped us blow past that. Today, we are extending that goal to 25,000. Millions turn to Vox each month to understand an increasingly chaotic world — from what is happening with the USPS to the coronavirus crisis to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work — and helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Emily VanDerWerff

Read More