Ghibli’s full catalog is coming to HBO Max. Here’s what to know — and what to watch first.

The arrival of Studio Ghibli films to HBO Max marks the first time the beloved Japanese animation studio’s legendary catalog will be available for easy streaming without having to buy or rent films individually. When the service launches on May 27, all but one of the studio’s 21 movies — animated masterpieces like My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, and many more — will be available to subscribers.

This landmark might not mean much if you don’t pay attention to animation or Japanese films. But Ghibli — pronounced “Gib-lee”; that’s a soft “g,” as in Gigi or gerbil — looms large over not only the landscape of animation but also the landscape of cinema itself. Co-founded in 1985 by a well-established but by no means well-known animator, Hayao Miyazaki, Ghibli’s painstaking animation process, distinctive visual style, and artistic storytelling techniques are revered in film schools the world over.

Because the studio’s decades’ worth of work took time to gain recognition outside of Japan, many people have yet to discover Ghibli films. And because only a few of those films have been available online — and even then, only on digital rental marketplaces — many of its devoted fans have yet to discover the full Ghibli catalog. (The only film in the Ghibli pantheon not arriving in May, The Wind Also Rises, will join the others on HBO Max later this year.)

So if you haven’t been able to catch them, either in a theater or on video/DVD while you were growing up, you might not be familiar with the enchanting Ghibli film library.

Just in time for the catalog’s momentous streaming launch next week, we’re bringing you a guide to the studio, as well as our list of must-see films by Hayao Miyazaki and other iconic Ghibli directors.

Studio Ghibli established itself as the home of Miyazaki, but all of its founders are animation giants

Born in 1941, Hayao Miyazaki was a child of war: His father manufactured parts for war planes, and to avoid bombing, his family had to relocate to a new city not once, but twice. Miyazaki started out as a manga artist, learning from innovators like Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy, Black Jack, Kimba the White Lion), but his focus on animation drew him to the industry straight out of college. Hired to do laborious grunt work at the well-established studio Toei Animation, Miyazaki threw himself into his art and gradually moved up the ranks to become a chief animator and storyboard artist.

At Toei, Miyazaki met Isao Takahata, an assistant director who had the chance to direct his first film just as Miyazaki was advancing as an animator. Takahata was five years older than Miyazaki, and likewise grew up during the war — he’d survived the bombing of Okayama in 1945, when he was 9.

While Miyazaki was strongly influenced by popular manga artists and animators, Takahata was heavily influenced by the French New Wave, a group of filmmakers who sought to deepen the artistry of cinema with experimental techniques and an emphasis on visual, kinetic storytelling. The men’s synergy of styles led to their first collaboration, with Takahata as director and Miyazaki as key animator, on 1968’s Horus, Prince of the Sun, a.k.a. The Little Norse Prince:

Takahata and Miyazaki worked so well together on this first film that they remained collaborators for the rest of their lives. Horus received plenty of critical praise at the time, and is widely seen today as an important film — but in what would become a pattern for their future work, the film’s production time ran long, mainly due to the painstaking perfectionism of its creators.

It took nearly three years for Horus to be completed, and the studio considered it a financial failure; Horus played in theaters for only a few weeks. But Miyazaki and Takahata now had a collaborative vision for the future. In 1971, they left Toei Animation together and went to work at a rival studio, A-Pro, and then another studio, Zuiyō Eizō, where they collaborated on several more films and series together.

Over the next decade, Miyazaki worked on animated films and series and also wrote and illustrated manga shows. By 1979, he was directing his first film, The Castle of Cagliostro. Takahata also continued to direct his own features and series, most notably the 1979 anime Anne of Green Gables, and they kept on collaborating.

In 1982, one of Horus’s biggest fans, an anime fanboy-turned-magazine-editor-turned producer, Toshio Suzuki, finally convinced Miyazaki to work with him after years of pitching Miyazaki on the idea. The project they came up with was a post-apocalyptic fantasy manga called Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which Miyazaki published in Suzuki’s magazine as a serial from 1982 to 1994. In 1984, with Suzuki and Takahata as producers, Miyazaki directed a film adaptation of Nausicaä, now considered the first Studio Ghibli film.

On the back of the film’s commercial success and bolstered by their shared ideals of artistic excellence, Miyazaki invited Takahata and Suzuki to form a new animation studio with him. He called it “Ghibli” — it sounds like “Jiburi” in Japanese — after the name of an Italian war plane, itself borrowed from the name of a hot Libyan desert wind. Miyazaki has called it a random name choice, but he’s also said it was meant to represent the disruption the studio founders hoped to bring to the industry.

And did they ever. Since the three men founded Ghibli together in 1985, they’ve gone on to create some of the most acclaimed and influential films ever made.

Studio Ghibli films have influenced a decade of animation and filmmaking

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19996640/arietty.gif) Courtesy of fyghibli/Tumblr

Courtesy of fyghibli/TumblrFrom the beginning, with Nausicaä and the studio’s first official film Laputa (Castle in the Sky), Ghibli established itself as a studio committed to the meticulous craft needed to make great, emotionally compelling animation. Even now, decades into the age of digital animation, Ghibli continues to utilize hand-drawn animation (alongside occasional computer assistance). Its films often take years to produce and animate because of this commitment, but that also keeps anticipation high.

Miyazaki helmed most of the studio’s most well-known films, and thus Ghibli has become synonymous with Miyazaki’s name and work. But Ghibli wouldn’t have become the source of excellent filmmaking that it did without Takahata’s expertise — and the rivalry between him and Miyazaki.

With Suzuki serving as company director and occasional peacemaker, Takahata and Miyazaki initially competed, each one racing to release their films before the other. In 1988, just three years into the studio’s existence, Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies and Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro were released in theaters as a double feature. They couldn’t be more tonally different, but each brought the studio acclaim, and critics now view them both as seminal works. The following year Ghibli released the most profitable Japanese film of 1989, Kiki’s Delivery Service, directed by Miyazaki.

The studio released films steadily throughout the next two decades, and Disney signed on as the studio’s U.S. distributor in 1996. Miyazaki’s Spirited Away garnered an Oscar for Best Animated Feature in 2002, the second year the award was given. (It remains the only anime to win the award.) The studio has since received four more Academy Award nominations — for Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), The Wind Rises (2013), The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), and When Marnie Was There (2014).

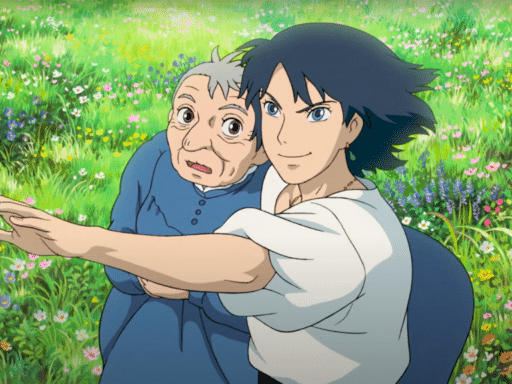

Ironically, the three back-to-back nominations came after a slow-down period for the company in the 2010s, as Miyazaki continually tried and failed to retire. In 2018, Takahata died at the age of 82. At age 78, Miyazaki is currently working on his next film, How Do You Live? Suzuki, who still serves as company manager, told Entertainment Weekly in a recent interview that the company used its streaming deal with HBO to finance the film’s production, and that Ghibli’s future depends on how well the next film does.

This is a familiar predicament for the studio, which has long been led by Miyazaki’s drive to produce one quality film at a time, without planning for a long-term future. But it’s a testament to the studio’s sterling reputation that it continues to be able to fund and produce new films.

Miyazaki and Takahata both emphasize grounded visual storytelling in their work, using rich scenic design to establish mood and locate the audience in a version of the “real” world. Their compositions reflect the aesthetic influence of mid-century filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu, carefully and very symmetrically layering people and background details in a state of tension. Both Ozu’s films and Ghibli films are steeped in the Japanese idea of mono no aware, an awareness of life’s transience that can yield a deep connection to things and moments, along with a fuller appreciation of beauty. It’s this type of meditative experience that Ghibli films are known for — an emphasis on feeling over plotting.

Ghibli films constantly reflect upon conflicting but necessary relationships between humans and their environment, and between society and individuals. Miyazaki’s stories in particular are heavily influenced by traditional Japanese animism and the belief that the natural world is inhabited by spirits. His commitment to realistic, detailed settings makes the magical elements of his storytelling believable. Because Miyazaki tends to work closely with his films’ composers, particularly Joe Hisaishi, who has scored nine Ghibli films, they also have a distinctive musical aesthetic that pairs with this cinematic tone.

Although most Ghibli films are made children, they’re often concerned with the slippage of childhood into adolescence, and their serious themes and sophistication make them popular with many adults.

Where characters in English-language animation tend to be divided simply into “good” and “bad,” Ghibli characters are often flawed and far more difficult to pigeonhole: Main characters make selfish mistakes, and villains are often sympathetic. Many Ghibli characters are deeply beloved and iconic, from Kiki in Kiki’s Delivery Service and Howl in Howl’s Moving Castle to Totoro and his Catbus to the friendly ghost No-Face in Spirited Away. There’s a popular Ghibli museum in Tokyo, and there’s even a planned Ghibli theme park on the way.

Ghibli has influenced decades of animation, with members of the studio going on to helm acclaimed films and anime of their own, and countless filmmakers and animators citing Ghibli films as an inspiration.

These include since-disgraced former Pixar head John Lasseter, who frequently played Miyazaki films at the studio just to keep animators inspired. The animators of Pixar’s Up drew directly from Miyazaki’s aesthetic for much of the film, including the main character design and the entire iconic opening sequence. Up director Pete Docter, who also directed dialogue for the US version of Howl’s Moving Castle, stated in 2009 that what’s arresting about Miyazaki are these “beautifully observed little moments of truth that you just recognize and respond to.”

“What we love about those films is that they just breathe,” Up producer Jonas Rivera added. “Not a day goes by that a Miyazaki film doesn’t come up in conversation.”

Nine must-watch Ghibli films

The true correct answer to “Which Ghibli films should I watch?” is all of them. But if you’re pressed for time or not sure where to start, here are the nine films you absolutely shouldn’t go without.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Though it was technically made before the studio was formed, its existence led to Ghibli’s formation, and the studio has long-since claimed it as one of its own. By any standard, Nausicaä is one of the best animated films ever made.

Gripping and gorgeous, its story of a parched post-apocalyptic world struggling to restore balance teems with suspense and sociopolitics. Nausicaä eschewed nearly every anime trope popular at the time in favor of letting its fiery heroine determinedly pursue peace with humanity’s enemies — a colony of enormous insects — before they’re eradicated. It all might just be a stand-in for modern, anti-war Japan attempting to navigate decades of Cold War politics. But even if allegory isn’t your thing, Nausicaä holds empathy for its characters — even and especially the giant bugs.

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

It’s likely that even if this story of children moving to a wooded land and befriending the sprites and spirits therein were the only thing Ghibli had ever produced, the studio would still be iconic. My Neighbor Totoro is just that wonderful — and its legendary title figure, a fun giant wood spirit, is just that cute. Between its vibrance, its delightful depictions of children and creatures, and its quiet, colorful exploration of coming of age, Totoro also thrums with poignance. Totoro feels ephemeral and fleeting, even when it’s indelibly captured on celluloid.

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

We won’t lie: This is widely considered one of the saddest films ever made. The plot — you watch a pair of children slowly fall into the margins of a society struggling to cope with World War II — is drawn both from autobiographical fiction and from Takahata’s experience of the war as a child. Grave of the Fireflies isn’t trying to find beauty amid violence, though it is beautiful; instead, it quietly, detachedly explores the connection and disconnection between humans that allow some of them to ultimately to be forgotten and lost forever. Roger Ebert called it “one of the greatest war films ever made,” and we have to agree — but again, it’s intentionally bleak and unrelentingly sad.

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

One of the most traditionally plotted of Ghibli’s films, Kiki’s Delivery Service really put the studio on the map. It was a legitimate blockbuster in Japan, and it’s easy to see why: Little witch Kiki and her black cat Jiji are absolutely adorable, and it’s impossible not to root for her as she finds her way in the world as she sets out on her own for the first time. But Kiki also has all of the other “typical” elements of a Ghibli film: quiet moments, breathtaking settings, and perhaps above all, an obsession with flight. [Editor’s note: It’s also the best movie ever made. Don’t fight me on this! If you disagree you’re wrong please don’t @ me ¯_(ツ)_/¯ —Allegra Frank]

Whisper of the Heart (1995)

Whisper of the Heart should have been director Yoshifumi Kondō’s entry into the world stage, with a film that announced his assumption of Ghibli’s legacy. Instead, his untimely death at 48, just three years after this film, threw the studio into a temporary creative lurch and meant that Whisper of the Heart stands as one of the sole testaments to a great animator and visionary. It’s a quizzical but beautiful entry into the Ghibli pantheon — a romance fantasy that’s also a frame story for another romance fantasy, that’s also a metaphor for storytelling and an exploration of the relationship between a story and its audience. With magical gentleman cats.

Princess Mononoke (1997)

All Ghibli films are to some degree concerned with animals and the environment, but Princess Mononoke is a kind of environmental war cry, as close to having an agenda as Ghibli has ever gotten. Its story of a boy and a feral girl fighting to save the spirit of the forest from human destruction echoes that of Nausicaä.

But Princess Mononoke is set in a familiar version of Japan, and its dark fantasy and horror elements are derived largely from an existential fear about the planetary destruction already at work. Princess Mononoke was one of the first Ghibli films dubbed into English — with a localized script by Neil Gaiman, no less — and though a vindictive Harvey Weinstein may have truncated its theatrical run after the studio refused to edit it, it gained a cult following and did well in a 2000 re-release. Thus it was the entry point for legions of fans into the world of Ghibli.

Spirited Away (2001)

Spirited Away won an Oscar and can make a good argument for ranking as Ghibli’s best film. Much like Pinocchio, Spirited Away literally spirits its heroine Chihiro away into a fever dream alternate reality, where she has to survive by befriending the right spirits, including the iconic ghost No-Face and the world’s hottest river spirit, and outwitting the wrong ones.

Spirited Away seamlessly blends all its archetypal folkloric elements into a subtle commentary on the clash of traditional Japanese values and modern-day consumerism, all while leaving you with a sense of having been spirited away yourself. Every Ghibli hallmark feels synthesized here into a perfect thesis statement about childhood, nature, mysticism, wonder, and the way all of those things constantly clash with modern society, industrialism, environmental decline, and even adulthood. For many people, Spirited Away is peak Ghibli — and thus the best.

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

Miyazaki has always loved fantasy literature, so it shouldn’t be surprising that the director chose to adapt fantasy author Diana Wynne Jones’ then-relatively obscure novel about a boy with no heart and the mild-mannered girl-turned-old-crone who loves him. But so much feels surprising about Howl: its fusion of its European-styled setting with its purely Japanese aesthetic (though book purists may be annoyed at the changes, but we all know book purists are awful); the sweetness of its romance contrasted with the darkness of its anti-war themes; and perhaps most of all the clanky, lumbering, wonderful moving castle itself. Oh, and have we mentioned Howl and Sophie are hot? They’re hot, and we’re not ashamed to say it.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013)

Takahata’s final film shows a master still at his peak just a few years before his death. Princess Kaguya has a highly distinctive visual style patterned after traditional Japanese line art, which fits the tale he’s telling — one of the oldest known Japanese fables on record.

This style allows Takahata to capture a kind of fluid watercolor emotion on screen, creating a unique take on this story of a beautiful girl mysteriously born in a bamboo plant and inadvertently thrust into conflict with the emperor after refusing his advances. Kaguya is surprisingly one of Ghibli’s most relatable — and timely — protagonists, a girl whose resistance to the men around her makes her a target. But that’s also why her story’s eventual soaring conclusion is ironically unforgettable: It may be based on a fairy tale, but it’s as real as Ghibli gets.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Aja Romano

Read More