And the rest of the week’s best writing on books and related subjects.

Welcome to Vox’s weekly book link roundup, a curated selection of the internet’s best writing on books and related subjects. Here’s the best the web has to offer for the week of February 24, 2019.

- At JStor Daily, Erin Blakemore looks at the two great love stories of Jane Eyre — between Jane and Rochester, and between Jane and herself — and why they’ve been making readers angry since the book came out:

In the 1840s, Jane’s love for herself was so subversive it bordered on revolution. In 2019, her love of Rochester is so shocking it borders on treason. In any era, its relationship to the love it explores is uneasy, volatile. Nearly two centuries after it was published, Jane Eyre confounds every expectation.

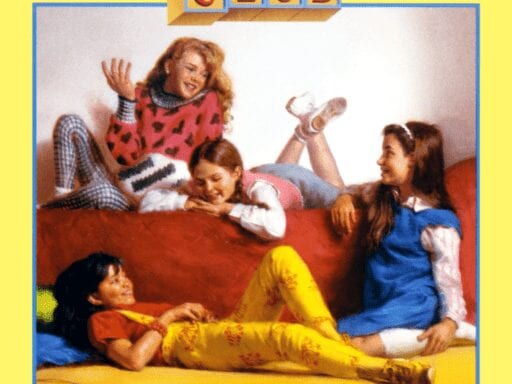

- Netflix is planning a 10-episode Baby-Sitters Club series, with GLOW’s Rachel Shukert as the showrunner. I, for one, demand a canon lesbian Kristy.

- A hypothetical book deal for Michael Cohen became quite the hot topic of conversation this week (Vox explained why here). Cohen does not currently have a book deal (his old one, from before he flipped on Trump, fell through), but the Washingtonian asked a few agents how much he’d get if he did.

- Atlas Obscura goes deep into the history of a 16th-century calligraphy manual. (Yes, there are pictures, and yes, they are gorgeous.)

It was common for a manuscript’s text and illuminations to be created by different artists. Bocksay had left room for illuminations around his pyrotechnic displays of penmanship. But the image of familiar flowers, delectable fruit, and animals from the Americas were not created during Bocksay’s life, but 15 years after his death. Their artist, Joris Hoefnagel, was hired by Emperor Rudolph II, Ferdinand’s grandson. Although the Flemish Hoefnagel never knew his Croatian counterpart Bocksay, he responded to the inscriptions with a matching degree of deftness and play. On a page where the text is adorned with curling shoots studded with black dots, Hoefnagel echoed the style with a drawing of pea pods. On another, trompe l’oeil ants crawl among the feathery, gilt tendrils of Bocksay’s work.

- At the New York Review of Books: a conversation between two literary intellectuals on whether it is right to no-platform a fascist, from 1945:

In the eyes of many writers at the time, Cerf’s refusal to reprint Pound’s poems adopted the same logic that the Nazis had used when burning books by Jews and leftists. In January 1946, a few weeks after the anthology appeared, the critic of the New York Herald Tribune, Lewis Gannett, criticized Cerf’s decision in his widely read column, Cerf replied, in a letter that Gannett printed: “Pound, by his deliberate and consistent actions over a long period of years, sacrificed any claims, in my opinion, either to the title ‘poet’ or the title of ‘American.’” Cerf continued, “Damn it, Lewis, this war is not over. The same ideology that caused it… is still too prevalent in the world. Every time you parade the work of a man who represents such ideas, especially while he still lives, you are in a sense glorifying him, and giving tacit approval to his point of view.” Cerf wrote that his partners Donald Klopfer and Robert Haas “firmly agree on this point.”

- CityLab’s Ariel Aberg-Riger has built a graphic love letter to the public library.

- At Affidavit, Audrey Wollen considers our cultural obsession with photographs of Marilyn Monroe reading:

In many cases, rather than proving Monroe’s intellectualism, the image’s “naturalness,” is used conversely to extrapolate on her naiveté: she couldn’t have comprehended her own meaningfulness, she must have stumbled into this iconic convergence of cultural objects. The background of children’s playground doesn’t help. Anyone can hold a book open. In a 2014 interview with Time magazine, Richard Brown, Joycean scholar, was asked if he believed she was “actually reading it” (emphasis in the original). He responds, “If you see someone in a picture reading a book, then they are reading that book.”

- Philip Roth’s Manhattan apartment is for sale, and it can be yours for a cool $3.2 million. A steal!

- At the Guardian, Alison Flood examines the history of literary plagiarism:

When she was 12, Keller wrote a short story called The Frost King. It was published and, as Keller recounts, “this was the pinnacle of my happiness” – until she was “dashed to earth” when the similarities between her story and Margaret T Canby’s The Frost Fairies emerged. “The two stories were so much alike in thought and language that it was evident Miss Canby’s story had been read to me, and that mine was a plagiarism,” wrote Keller. She was subjected as a child to a formal investigation at the Perkins Institution for the Blind over whether or not she had plagiarised deliberately. It acquitted her; although she admitted she must have read Canby’s story, she could remember nothing of it. “I have ever since been tortured by the fear that what I write is not my own,” she wrote.

- At Electric Lit, Kristen O’Neal investigates a website that seems to be generating weird short stories about phone numbers:

When you go to https://5613273737.phonesear.ch/ — where the ten-digit number can be swapped out for many functional phone numbers — the first three sections you see are standard. Phone number, location, phone company. But below these is a section simply labelled “Comments,” filled with hundreds of words of text assembled like a short story. Each sentence, sometimes two, stands alone, jumbled into paragraphs with unrelated sentences.

Some are mundane: “The logs are being floated down the river. This road needs to be repaved.” Some, taken together, are biting: “I want you to think about what really matters to you. That was a good joke. Tell us another one.” And some — especially the outward-facing sentences that seem to speak directly to the reader — send a chill up your spine: “His eyes are glowing. Is anybody looking for you?”

- At LitHub, Yewande Omotoso writes about the problem of being pigeonholed as “an African writer”:

A man, third row from the front put his hand up, his question was for me. He spoke and it took a few seconds to really understand what he was saying or rather it took me a few seconds to assure myself that what he was asking was really what he was asking. He, a middle-aged white man had bought a ticket and attended our talk, he’d listened to us give our African Perspectives, and now here he was informing me that he owned a wooden giraffe apparently from Kenya. Could I, the man appealed in a most earnest tone, help by explaining more to him about his giraffe.

Here’s a rundown of the past week in books at Vox:

- The Magicians paid off 74 years of queer subtext this week

- Is capitalism worth saving?

- The new reactionaries

As always, you can keep up with Vox’s book coverage by visiting vox.com/books. Happy reading!

Author: Constance Grady

Read More