The new art doesn’t address any of the underlying issues about ethics, exploitation, and corporate greed.

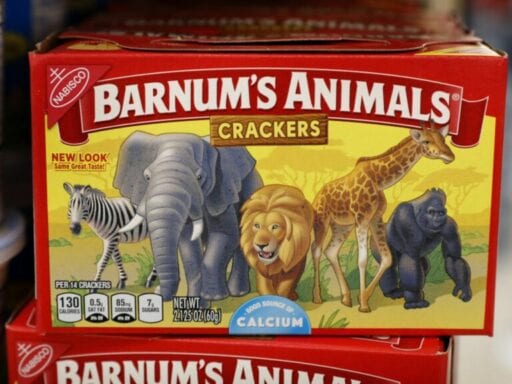

Nabisco’s animal crackers are a staple of American snack food aisles, and the box — a red-and-yellow rectangle featuring brightly colored circus animals cavorting in cages — is instantly recognizable. Just last week, though, Nabisco’s parent company Mondelez International announced it will change the design of the box. Instead of depicting the animals behind the bars of a circus wagon, it will show them striding free along a savannah.

The change is the result of a recent successful lobbying effort by PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), which said, “No living being exists simply to be a spectacle or to perform tricks for human entertainment, yet all circuses and traveling shows that use animals treat them as mere props, denying them everything that’s natural and important to them.”

Though the change is symbolic, it stirs up some mixed feelings for me ethics-wise as well as personally — because the designer of the previous box was my great-grandfather’s brother. Swapping the art on the box doesn’t address the real issues PETA raises, but it does do a disservice to my uncle’s art and legacy.

My uncle’s design was about joy, not cruelty

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12647447/animal_crackers_uncaged.jpg) Associated Press

Associated PressThe New York Times reports that this design had been in place since 1902, but according to the paper’s own records, commercial artist Sydney S. Stern (my great-granduncle) designed the recognizable packaging after he joined Nabisco in 1923.

Uncle Sydney died in 1989 at age 99, two years before I was born, so I never got to meet him, but I believe his design wasn’t about animal cruelty; he was thinking about joy. A vintage poster for his animal cracker design reads, “A circus for children,” and shows the animals marching out of the box. Stern added a polar bear to the box so that it would have more color variation, and a string so that the box could be used as an ornament. Much like his idea to call a new cracker “Ritz” despite it being the height of the Great Depression, his art thrived on being a light in a dark time.

His own life was far from easy. Sydney was one of six siblings, raised by Hungarian immigrants in a cramped tenement in lower Manhattan. Despite the family’s humble roots, each of the siblings was very successful. One brother, Eugene, went on to become a prominent architect in Little Rock, Arkansas, and designed the high school that would later become the backdrop for civil rights integration.

As members of the Jewish community, the family fared much better than my relatives who stayed in Budapest and lost their property, and in some cases their lives, to Nazism followed by iron-fisted Soviet rule by proxy. Uncle Sydney was able to study at the Art Students League, Columbia University, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and work as an independent commercial artist.

But in the 1920s, his wife died from childbirth complications, and he was unable to take care of the infant, Henry, on top of the two children he already had. He made the heartbreaking decision to place Henry in a home for infants and took a full-time job at Nabisco Biscuit Company in hopes that the steady 9-to-4 role would allow him the stability to welcome Henry back home. Within three years, the family was back together.

Redesigning the box doesn’t remedy the inequalities in play

Norms since those times have changed, including the public consensus around the prospect of animals being abused for entertainment. Yet the symbolic significance of changing the animal cracker box design does little to dismantle the elements of capitalism that exploit animals, people, and the environment. When art in advertising bears the burden for corporate malpractice, the people involved in these changes get to feel good, but other mechanisms continue to thrive under the surface.

Before she stepped down last year, Mondelez CEO Irene Rosenfeld was making 402 times more than the company’s median worker, according to the Chicago Tribune. That’s $17.11 million to the median of $42,893 (which, to reiterate, is not the company’s lowest salary).

In 2016, when Mondelez moved some of its production to Mexico, it claimed it gave the workers union a choice between moving and another option: to chip away at the $46 million a year they would save by moving — a chance to save their jobs. That other option? A 60 percent pay cut, at minimum, according to the Los Angeles Times.

This level of corporate greed cannot be fixed with a new box design, but if there are ways to use public-facing artworks to change the conversation, it seems Mondelez is more than willing to do it. The company certainly doesn’t seem to value its history — or the legacies of the people who contributed to it.

Nabisco was acquired by Philip Morris (the tobacco company) in 2000 and merged with Kraft Foods, which then split into two separate companies, with Mondelez specializing in snack foods.

When I was writing about Uncle Sydney in 2016 for Food & Wine, I was able to get in touch with a former corporate archivist at Kraft, one of the people responsible for maintaining the company’s historic records. She said that after the merger there was no Nabisco archivist, and possibly no archive. As far as I know, the best archive of midcentury Nabisco box design is at Uncle Sydney’s son’s home in New Jersey, where the artwork fills multiple rooms.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12648101/GettyImages_507226466.jpg)

Do you know who designed the Campbell’s Soup can label? Probably not, but you certainly know Andy Warhol because he was a “real” artist. If you’ve seen Mad Men, you know that in-house artists and marketers often work in teams. Many gifted artists without the money to pursue a career in fine arts turned to commercial art as their day job and became nameless contributors to the brand’s public face.

Being a “real” — meaning, not commercial — artist comes with certain protections for one’s legacy. The public is more willing to accept outdated values when they are under the auspices of art. Take Balthus, for example. Last year, thousands of people unsuccessfully petitioned the Metropolitan Museum of Art to remove the modern artist’s painting Thérèse Dreaming (1938), which can be seen as a sexually suggestive depiction of a young girl by a much older man. By common parlance, it’s “problematic,” but because it is considered art, to remove it would be censorship.

I don’t believe that what PETA’s animal cracker box campaign has done is censorship, but I do believe it places an unfair burden on an artist’s contribution without addressing any of the deeper ethical issues in play.

As it stands, my family is divided on whether the box redesign is the right thing. Our thread about these changes morphed into to talking about almond milk (good for animals, bad for water rationing), whether it’s ethical to wear fur if you inherited it (the animal is already dead!) and why we’re glad Monsanto is finally being nailed in court over Roundup — even though its new parent company, Bayer, is possibly saving the bees.

Society is set up so that we have to make small ethical choices because the biggest ones are too hard to tackle. Now my uncle’s art has become a part of this cycle. So if you see me at the grocery store buying up the remains of his public legacy, it’s not because I don’t care about the ethical treatment of animals, or people, for that matter.

It’s because the animal crackers box is my Balthus.

Daisy Alioto is a writer living in the Hudson Valley.

First Person is Vox’s home for compelling, provocative narrative essays. Do you have a story to share? Read our submission guidelines, and pitch us at [email protected].

Author: Daisy Alioto