Russia is poised to hack again. Here’s how the media should respond.

The indictment of a dozen Russian intelligence operatives offered new details about how Russia hacked into the communications of Democratic officials during the 2016 election. Information exposed in the hack provided fodder for countless news articles about internal Democratic Party discussions. In March, Nathaniel Zelinsky made the case that journalists and social-media platforms can voluntarily reduce the damage to democracy caused by foreign hackers:

It may be time for patriotic citizens who want to preserve the integrity of our democracy to start thinking outside the box about how we can prevent Russia from meddling in our elections.

In that vein, consider this admittedly radical idea: American journalists should take a pledge to not report the contents of a hack, and social media sites should remove from their networks any news stories discussing hacked material.

This commitment — call it the “responsible journalism pledge” — would be an extraordinary step for writers and editors who pride themselves on their independence and bristle at outside suggestions to limit their reporting. It would also represent a marked shift in how traditional journalists and social media firms operate.

Most reporters distance themselves from questions about the origin of information, so long as it remains verifiable, while tech companies tend to believe no one should restrict access to information on the internet. But at this particularly dangerous point in our nation’s history, reporters and Facebook alike just might be willing to embrace a new ethical obligation out of a sense of civic duty.

One reason is that the Trump administration appears reluctant to do much about Russian hacking. National Security Agency Director Adm. Mike Rogers testified in February before Congress that President Donald Trump had yet to order the NSA to combat Russian interference in America’s 2018 midterm elections. The administration also dragged its feet on implementing congressionally mandated sanctions on Russia.

What’s more, according to the New York Times, as of March “the State Department [had] yet to spend any of the $120 million it has been allocated since late 2016 to counter foreign efforts to meddle in [overseas] elections or sow distrust in democracy.” In the meantime, the Washington Post has reported that Russian hackers may already be targeting Senate staffers’ email accounts, so another of Moscow’s trademark email dumps may be just around the corner.

Enter the press, social media sites, and a self-constraining pledge.

The pledge wouldn’t mean declining to report that the DNC had been hacked

At the outset, it’s important to note what this pledge would and would not entail. In essence, journalists abiding by it would promise to refrain from doing what they did in the 2016 election: packaging the information unearthed by Russian hackers into narratives that American voters could understand. In the runup to the presidential election, whenever Russia’s intermediates released stolen emails, reporters eagerly mined the dumps of hacked communication for salacious tidbits that created an aura of political scandal but at the same time did not add meaningfully to the public discourse.

Consider the 20,000 or so emails stolen from Democratic National Committee servers before the Democratic National Convention. The main supposed “revelation” — that senior Democratic Party officials supported Hillary Clinton’s nomination over Bernie Sanders’s — was no surprise to even casual observers of politics. (Vox was among the many publications that reported on the DNC hacks and published some of the contents of hacked emails.)

The version of the pledge taken by the social media sites would be similar: They’d decline to provide a digital megaphone to publications that did report on the content of hacked material. That would limit the pageviews of those journalists who refused to follow the pledge.

The pledge would hardly mean a blackout on news about hacks: Journalists, though they would vow not to report the precise contents of cybertheft, could still report the general fact that a hack occurred, and people could still share such stories on social media.

The pledge also would not prevent the media from reporting about leaked information, including leaks of classified material, which are often mistakenly conflated with hacks.

Leaks occur when an insider within the government or other organization provides information to an unauthorized party. The government can prosecute leakers to discourage leaks in the first instance — though as a practical matter, the government tends not to pursue leakers, for a variety of reasons.

In contrast, hackers infiltrate their targets from the outside and can operate outside the effective reach of American law enforcement. In theory, the United States can respond to state-sponsored hacks with economic sanctions, a cyber counterattack, or even military force. But in practice, it can be difficult to craft a foreign policy that measurably deters an adversary but simultaneously does not spiral into a dangerous conflict.

And that’s in the best of times. Deterring a hostile power like Russia becomes almost impossible when the president possesses ulterior motives.

One could reasonably suspect that President Trump — who openly admires Vladimir Putin and often denies Russian meddling in the 2016 campaign — is not wholeheartedly committed to deterring and punishing Russia.

The Supreme Court could conceivably uphold legal restrictions on publishing hacked information

As I have argued elsewhere, it is possible that the difficulty of stopping state-sponsored hackers leaves room for Congress to pass legislation punishing newspapers that published hacked material. In an important 2001 case, Bartnicki v. Vopper, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment prevented the government from imposing civil liability on a radio station that broadcast an illegally intercepted cellphone call. (The case was from a time in which wireless communication was far less secure.) Crucially, in Bartnicki, the radio station itself had not engaged in the illegal interception but was simply the passive recipient of the illegal recording.

The government tried to defend imposing liability on the station on the grounds that discouraging the station from broadcasting could help to “dry up the market” for stolen information. But the Supreme Court rejected this argument, noting that if the government wanted to protect private communication, it should instead find and prosecute the actual phone interceptors.

Federal courts have wrestled with Bartnicki’s implications since 2001. It’s conceivable that in very narrow circumstances — as in the case of hard-to-discourage foreign state-sponsored hackers — courts might be tempted to conclude that imposing liability on the press to “dry up the market” is the only way to deter illegal activity.

But such a law would set a dangerous precedent, altering the relationship between the government and the press in fundamental ways. Far better, then, if journalists and social media companies voluntarily work together to ameliorate the harms that hacks pose to our society.

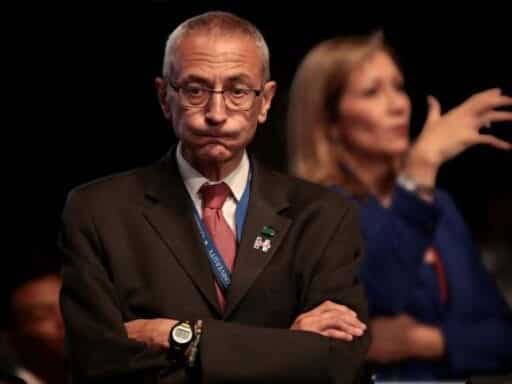

To be sure, obvious objections abound, and the press will most likely resist adopting the pledge. Nicholas Lemann, a professor of journalism at Columbia, told me that he “made a private vow to not publish” any of the material emanating from the hack of John Podesta’s emails during the 2016 campaign.

Still, despite describing himself as “empathetic” to the concept of journalistic self-censorship, he is convinced it’s impossible in practice. Once a “less reputable player publishes,” according to Lemann, “a mainstream player cannot avoid it.”

But I’m a little more hopeful. Pew polling suggests that a large percentage of Americans still consume news via established outlets: “57% of U.S. adults often get TV-based news, either from local TV (46%), cable (31%), network (30%) or some combination of the three.” If these mainstream stations refused to provide a platform for hacks, a good number of Americans might never come across them.

Social media companies can have an even greater impact. According to Pew, 67 percent of Americans reported having used social media for news at some point; 20 percent said they did so often. Indeed, the commitment to this agreement by the two dominant networks, Twitter and Facebook, should quell the concerns of some journalists that if they don’t report the contents of a hack, one of their competitors will — and the rogue article will go viral. Without retweets and shares, such stories will reach a vanishingly small number of readers.

Is it unreasonable to expect traditional news organizations and social media sites to exercise this degree of self-restraint? I don’t think so. These companies already abide by a host of professional norms that limit what they report.

During ISIS’s rise, major television networks and sites like YouTube enacted more aggressive policies aimed at flagging and removing graphic, unedited ISIS propaganda videos from the site. While it hasn’t worked perfectly, unless someone intentionally seeks out ISIS propaganda online, they’d be hard-pressed to accidentally come across a full-length ISIS beheading video today.

Similarly, reporters frequently weigh the harms of disclosing classified material against the potential benefit to the public of their disclosure (and even consult with government officials in such cases). In 2017, CNN withheld key details from a story about terrorists using laptop bombs to protect sensitive sources and methods. Journalists, too, almost universally decline to reveal the name of rape victims, though the First Amendment clearly protects their right to do so.

If the media declined to publicize the contents of hacks to protect our democratic institutions from foreign interference, even skeptical reporters might come around to the view that this is an analogous act of noble sensible self-restraint.

To avoid the charge of partisanship and bias, it’s crucial that journalists and social media companies take the pledge in advance of a hack — and, ideally, well before the midterm elections. If they wait for a hack to occur to pronounce this new professional ethic, whatever political party benefits from the hack will accuse reporters of seeking to protect the other side. If media organizations do so today, the charge that they’re politically motivated is less likely to stick.

To be sure, some journalists will not abide by the pledge; no voluntary professional norm will ever be 100 percent effective. But in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, reporters and social media companies have recognized anew their civic responsibilities in a free society.

If slogans like “Democracy Dies in Darkness” mean anything, they mean the press should play a part in protecting America’s most basic political processes against our foreign foes.

Nathaniel Zelinsky is a member of the Yale Law School class of 2018. He holds a master’s degree in philosophy from the University of Cambridge, where he researched propaganda in historical and contemporary contexts. This article draws on arguments he made in the Yale Law Journal.

The Big Idea is Vox’s home for smart discussion of the most important issues and ideas in politics, science, and culture — typically by outside contributors. If you have an idea for a piece, pitch us at [email protected].

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png