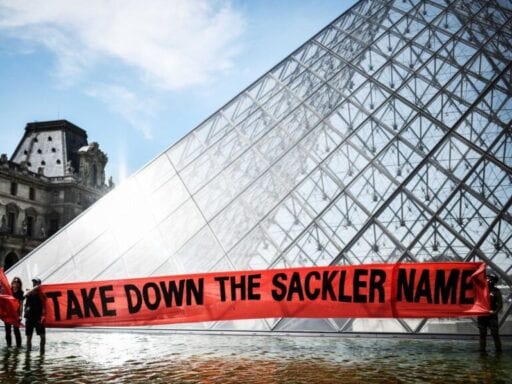

Opioid company executives and owners are set to walk away from the drug overdose crisis as billionaires. There’s another way.

The Sacklers, the family behind OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma, will likely pay billions of dollars for their role in causing the opioid epidemic. But when the cases are settled, they will walk away from the lawsuits — and the opioid epidemic they and Purdue helped cause — still billionaires.

Purdue, which is owned by the Sacklers, introduced and aggressively marketed the opioid painkiller OxyContin in 1996. Since then, more than 200,000 people have died of painkiller overdose deaths, with another roughly 200,000 dying from other opioids — in many cases, after using painkillers first.

Purdue was one of the companies at the forefront of the misleading marketing of opioid painkillers, pushing doctors to prescribe more and more of the drugs and claiming that OxyContin was safe and effective, even after news stories about addiction and overdoses surfaced, according to lawsuits filed against the company and reporting on its marketing.

The same lawsuits and reporting shed some limited light on the role of several members of the Sacklers, many of whom have been named in lawsuits — most notably, Richard Sackler, who was president of Purdue after OxyContin launched and was closely involved in messaging and marketing for the drug.

A settlement agreement for the thousands of lawsuits nationwide against Purdue and the Sacklers could total as much as $10 to $12 billion, with at least $3 billion from the family. As part of the deal, Purdue will declare bankruptcy and turn into a trust whose profits will go to the lawsuits’ plaintiffs, and the Sacklers will sell off their international drug company, Mundipharma, to help pay for the settlement.

But according to Forbes, the family “will still be worth between $1 billion and $2 billion, down from a current net worth estimate of $11.2 billion.” That is likely an underestimate, given recent reports alleging the Sacklers have billions secretly stashed away overseas.

The lawsuits are, according to the plaintiffs, meant in part to stop future companies like Purdue from misleading and aggressively marketing dangerous products. But how much of a deterrent is it if the company’s owners are left with more money than they could ever hope to spend in their lifetimes?

“If [the Sacklers] have the perception — and it’s the correct perception — that ‘people like us just don’t go to jail, we just don’t, so the worst that’s going to happen is you take some reputational stings and you’ll have to write a check,’ that seems like a recipe for nurturing criminality,” Keith Humphreys, a drug policy expert at Stanford University, told me.

There is, however, one way to make sure the Sacklers — and the owners and executives of other companies also facing lawsuits over their role in the epidemic, including Johnson & Johnson, Endo, and Teva Pharmaceutical — don’t walk away from this largely unscathed: criminal charges, with the possibility of prison time. (Representatives for the Sacklers did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19269744/GettyImages_1134500877.jpg) Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Drew Angerer/Getty ImagesFederal or state officials could investigate, as lawmakers like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have called for, specific members of the Sackler family — particularly those closely involved with Purdue — and other opioid company executives and owners, and they could bring criminal charges. This would go beyond recent lawsuits, which remain civil matters with no threat of jail or prison time. It’s the kind of action the feds have taken against some smaller players in the opioid crisis, like Insys Therapeutics, but have yet to take seriously with larger actors.

The federal government had a chance to hold Purdue and its leaders accountable once before. After a federal investigation in the mid-2000s, journalist and Pain Killer author Barry Meier reported, “The Justice Department had an opportunity to prosecute the executives of Purdue. That was the recommendations of the prosecutors on the case; they wanted these individuals to be charged with serious crimes.”

But the Bush administration blinked. Instead, Purdue and three executives pleaded guilty in 2007 to charges related to “misbranding.” The three executives, including then-President Michael Friedman, were each sentenced to three years of probation and 400 hours of community service, and they had to pay tens of millions of dollars in fines. But they served no prison time.

In the years after, America’s opioid epidemic continued getting worse. In 2007, overdose deaths for all drugs were 36,000, with nearly 13,000 linked to prescription opioids. In 2017, the latest year of data available, overdose deaths for all drugs hit 70,000, with 17,000 linked to prescription opioids.

America now has a chance at a do-over. It won’t be easy; the Sacklers, Purdue, and other opioid executives will have a lot of money to throw at a high-powered legal defense. A thorough criminal investigation will be needed to learn the Sacklers’ and other executives’ full involvement, and it’s not yet clear what charges could stick in a prolonged legal battle.

But merely prosecuting the case could be an opportunity for the US government to show it takes executives’ wrongdoing seriously. The Sacklers and others who became rich from opioid painkillers have benefited from the same culture of impunity that sent just one top banker — and not a particularly high-level one — to prison after the 2008 financial crisis.

The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, which tracks federal law enforcement, found in September that federal white-collar criminal prosecutions “are only half the level of just eight years ago. In fact, this year is on its way to achieving a record low — the lowest ever since records began back in FY 1986.” If you’re a corporate executive interested in potentially illegal but profitable activity, the message is clear: You can do it, make a ton of money, and almost certainly get away with it.

“You can go to prison for accidentally killing one person with your car. That’s the minimum standard,” Rick Claypool, a research director at Public Citizen, told me. “The idea that you can run a company and cause societal-level devastation and walk away from that relatively unscathed is mind-boggling.”

How OxyContin helped lead to the opioid epidemic

The release of OxyContin in 1996, and the aggressive marketing campaign that surrounded the drug, started the proliferation of opioid painkillers. Historically, the drugs had been used for palliative care for terminally ill patients and in a few acute settings, such as after a surgery. Purdue wanted doctors to prescribe opioid painkillers more commonly for all kinds of acute and chronic pain.

Purdue’s core message was that OxyContin was both safer and more effective than other painkillers on the market, so it could be safely used to treat more kinds of pain than past opioids.

A group of experts explained Purdue’s role in a 2015 Annual Review of Public Health article:

Between 1996 and 2002, Purdue Pharma funded more than 20,000 pain-related educational programs through direct sponsorship or financial grants and launched a multifaceted campaign to encourage long-term use of [opioid painkillers] for chronic non-cancer pain. As part of this campaign, Purdue provided financial support to the American Pain Society, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the Federation of State Medical Boards, the Joint Commission, pain patient groups, and other organizations. In turn, these groups all advocated for more aggressive identification and treatment of pain, especially use of [opioid painkillers].

As part of this effort, opioid companies and their astroturf groups branded doctors who continued to prescribe opioids cautiously as inflicted with “opiophobia.”

In the ensuing years, the number of opioid prescriptions grew — to the point the US now far outpaces any other country in opioid prescribing. Addiction and overdose deaths followed.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5999533/opioid%20trend.png) Annual Review of Public Health

Annual Review of Public HealthBut Purdue’s claim about OxyContin’s safety and efficacy was wrong.

OxyContin is an extended-release opioid, meaning its active ingredient is supposed to disseminate into the body over a long period of time to spread out the effects and avoid causing a high or an overdose. Purdue claimed this made OxyContin safer than other opioids.

But people learned OxyContin could be crushed and snorted or injected to get the full effect. This was actually more dangerous, delivering opioids meant to be disseminated over hours in one hit. Misuse and addiction proliferated, among not just patients but also friends and family of patients, teens who took the drugs from their parents’ medicine cabinets, and people who bought excess pills from the black market.

OxyContin also wasn’t as effective as claimed. The drug was marketed for its supposed ability to provide 12 hours of pain relief. But as Harriet Ryan, Lisa Girion, and Scott Glover reported for the Los Angeles Times in 2016, that wasn’t true — and there were warning signs during drug trials, even before OxyContin went to market.

Purdue, however, ignored concerns and encouraged doctors to just prescribe higher doses if patients didn’t get the 12-hour relief they were promised — putting the patients at higher risk of overdose and addiction.

“More than half of long-term OxyContin users are on doses that public health officials consider dangerously high, according to an analysis of nationwide prescription data conducted for the Times,” the newspaper found.

There’s also only very weak scientific evidence that opioids can effectively treat long-term chronic pain as patients grow tolerant of the drug’s effects. So OxyContin isn’t even as good as one might think for pain relief.

The Sacklers led Purdue for much of the opioid crisis

From the 1990s on, Purdue was run in large part by the descendants of Mortimer and Raymond Sackler, the brothers who founded the company and served as chief executives.

Richard Sackler, Raymond’s son, was the company’s president from 1999 to 2003 and later its co-chair. Six other Sacklers served on the board as the opioid crisis mounted: Raymond himself, who died in 2017; his wife Beverly Sackler; Mortimer’s children Ilene Sackler Lefcourt, Kathe Sackler, and Mortimer David Alfons Sackler; and Raymond’s son Jonathan Sackler, who is Richard’s brother. Another, David Sackler, Richard’s son, joined the board in 2012. (As of 2019, all Sacklers have stepped down from the board.)

It’s these members of the family who have been blamed for the opioid crisis, including in some of the lawsuits filed against Purdue and the Sacklers, and who could be targeted for prosecution.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19269787/GettyImages_1090645452.jpg) Suzanne Kreiter/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Suzanne Kreiter/The Boston Globe via Getty ImagesThese lawsuits have started to reveal what the company knew, and when it knew it, as the opioid epidemic took off. A filing this year in Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey’s lawsuit against Purdue and the Sacklers exposed that Richard Sackler, then president of Purdue, didn’t care much for reports of misuse and addiction. In 2001, after 59 deaths from OxyContin were reported in one state, Richard Sackler responded in an email, “This is not too bad. It could have been far worse.”

That same month, Richard Sackler tried to shift the blame to people addicted to drugs, writing that “we have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible. They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”

The company and the Sacklers also allegedly ignored — for years — excessive prescribers, even as their own staff warned of pill mills that should have been reported to federal officials.

A criminal investigation could reveal more. For instance, we only recently learned from the lawsuits that the Sacklers may have moved money from Purdue to personal accounts more than a decade ago in an attempt to avoid paying fines — which, if true, could be fraudulent conveyance, a crime, according to reporting by Renae Merle and Lenny Bernstein for the Washington Post.

To date, Purdue and the Sacklers continue insisting on their innocence. David Sackler, who was on Purdue’s board of directors as recently as 2018, told Vanity Fair this year, “Facts will show we didn’t cause the crisis.”

The legal case is difficult but worth taking seriously

It is not illegal for a pharmaceutical company to sell its products, even potentially risky ones, as long as it has approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

Where Purdue and the Sacklers went wrong is in misleadingly marketing their products, claiming they were safer and more effective than they really were for years.

University of Iowa law professor Mihailis Diamantis said the misleading marketing opens Purdue — and potentially the Sacklers, depending on how involved they were — to charges of misbranding, illegal drug distribution, and conspiracy or racketeering. One possibility is charging the Sacklers under the responsible corporate officer doctrine, which attempts to hold company leadership accountable for wrongdoing by the people under them.

There’s a precedent here, including the 2007 case over misbranding.

This year, a court criminally convicted Insys executives, and the feds criminally charged distributors Rochester Drug Cooperative and Miami-Luken. While there are legally important differences in how Purdue and these other companies behaved, they’re broadly accused of the same kind of wrongs.

For example, Rochester and Miami-Luken are accused of failing to report suspicious orders of opioids, even when they should have known the drugs were going to non-medical uses. Purdue reportedly kept a list of doctors who were excessive prescribers, but it seldom turned in doctors to government agencies — and used the list for personal gain. It cited it to take down generic competitors by claiming a generic version of OxyContin was too dangerous, as the company conveniently released a new misuse-deterrent version of OxyContin.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19269874/GettyImages_1132987037.jpg) Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe via Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19269942/GettyImages_1079999298.jpg) Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe via Getty ImagesThe legally tricky thing, experts say, is the leap from Purdue’s wrongdoing to the Sacklers’ personal liability. Based on the lawsuits, it might be relatively straightforward to make a case against Purdue as a whole and executives who were directly involved in misbranding and misleadingly marketing opioids. But the Sacklers, especially in more recent years, may have played a less direct, high-level role on the board of directors. The question becomes just how involved the Sacklers were in the day-to-day dealings of the company and how much of a role they had in any misleading marketing efforts.

“There’s a separate question of whether you can get something against the Sacklers themselves,” Diamantis told me. “That’s where the difficulty comes.”

There’s some evidence the Sacklers were pretty involved. According to Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey’s lawsuit against Purdue and the Sacklers, members of the Sackler family regularly got reports on opioid marketing efforts. As part of this, they were once given a list dubbed “Region Zero,” which tracked doctors “who were suspected of diversion and abuse.” In the same meeting, the lawsuit said, “the Sacklers voted to expand the sales force by 125 more sales reps.”

The Sacklers would continue pushing the company to aggressively market opioids. Based on the Massachusetts lawsuit, Richard Sackler, in particular, demanded regular updates on what was being done to boost sales numbers. He was especially interested in pushing the marketing and sales of stronger doses because those brought in the biggest profits.

The Sacklers and Purdue have vigorously denied the allegations in the Massachusetts lawsuit, claiming that communications and other information have been taken out of context.

At the least, though, what we know is very suggestive. Whether it’s enough for a full criminal prosecution against any member of the Sackler family is an open question. It all depends on how closely potentially illegal marketing and other unlawful activities can be tied to individual family members, instead of Purdue as a whole.

Similar concerns could apply to other opioid company owners and executives, who may have taken steps to insulate themselves from some of their businesses’ shadier dealings.

But that’s exactly why criminal charges should be taken seriously: A Justice Department investigation could substantiate the wrongdoing that’s already suspected — and uncover more. Only then will we get some real answers.

There are some reports that the federal government is undertaking some sort of investigation into Purdue and, perhaps, the Sacklers, but they’re unconfirmed. A Justice Department spokesperson declined to comment, saying “the department generally neither confirms nor denies whether a matter is under investigation.”

The justice system is supposed to keep Americans safe, hold criminals accountable, and deter would-be wrongdoers. If opioid company owners and executives like the Sacklers caused societal devastation and are allowed to get away with criminal activity, the system is failing at one of its core purposes.

Or as Diamantis put it, “If the Sacklers get to walk away, after decades of improperly marketing this opioid, as one of the richest families in the United States, you have to ask yourself: Is the criminal justice system appropriately or effectively deterring such conduct from Sackler families in the future?”

This is a chance to fight a culture of impunity

In general, the progressive impulse — and mine too — is to push for less incarceration and criminal punishment in general. But there’s a special argument for going after the Sacklers and other opioid executives. It’s what’s known in criminal justice policy as the “certainty of punishment”: People should know that if they commit crimes or cause harm, they will be held to account.

Over the past several decades, as federal and state governments have escalated mass incarceration and the war on drugs, they’ve mostly focused on severe punishments, such as harsh mandatory minimum prison sentences. But the research suggests that certainty of punishment matters far, far more than the severity.

In 2016, the National Institute of Justice summarized the evidence: “Research shows clearly that the chance of being caught is a vastly more effective deterrent than even draconian punishment.” They added, “Research has found evidence that prison can exacerbate, not reduce, recidivism. Prisons themselves may be schools for learning to commit crimes.” So more certainty of punishment can deter crime, while more severity can actually make it worse after a certain point.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19269906/GettyImages_1167644926.jpg) Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty ImagesThere’s a common sense element to this: People tend to commit crimes thinking they’ll get away with them, so whether they’re punished by 10, 20, or 100 years in prison is really not that important. But if you change the notion that they can get away with crime — by making it more likely the criminal justice system will punish them — then you can make an impact.

“Instead of a ratcheting up of punishment or desire to make sure these guys really feel the impact, we should focus instead on ratcheting up prosecutions — so executives know that they’re on notice and you can’t get away with this,” Ashley Nellis, a senior research analyst at the Sentencing Project, told me.

Now apply this to the Sacklers and other opioid executives. If they or their buddies think that they will get away with causing a major drug overdose crisis with no real punishment, the deterrence effect is going to be zero. So what are they or people like them going to do the next time they have a potentially risky product that could make them a lot of money?

Severity of punishment does matter to some extent. Given how rich the Sacklers are, it’s unlikely that any legal settlement or fine will make a serious dent in their wealth. (The $10 to $12 billion legal settlement covers only a third of the more than $30 billion the company and family have made from OxyContin since the 1990s.) That’s why the possibility of prison time is important here, too — that would have a real impact on opioid executives’ lives, even if the fines and legal settlements fall short.

And while some smaller players like Insys are facing the potential of serious punishment, the fact the Sacklers, as perhaps the biggest contributors to the opioid crisis, may come out of this without the possibility of a criminal prosecution sends a message of impunity — that maybe fines and lawsuits are just the small cost of taking part in an otherwise very profitable business.

As Humphreys, of Stanford, put it, “It would be a powerful deterrent within that group that yes, in fact, no matter how many country clubs you belong to and how many museums you endow, you can still end up behind bars.”

Author: German Lopez

Read More