Some people avoid them at all costs. I seek them out — and I’m not alone.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

On the evening of March 15, 2015, across America, phones shoved into jeans pockets or left to rest on dinner tables buzzed to life with a New York Times news alert, which was also tweeted from the newspaper’s official account.

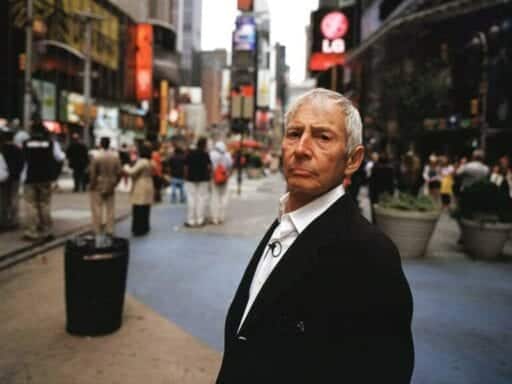

“Breaking News: In Documentary, Robert Durst Says He ‘Killed Them All,’” the alert read. The documentary was The Jinx, HBO’s six-part miniseries about the eccentric real estate heir Robert Durst and the murders he may or may not have committed, and that night, the final episode was set to air.

The problem was that for millions of viewers on the West Coast — and anyone who’d planned to watch later — the Times had just given away the big twist.

Directed by Andrew Jarecki, the series instantly grabbed viewers and critical interest. The show’s central mystery was sordid and addictive: Did the wealthy, weird Durst kill three women (including his wife), no women, or some other configuration thereof? Or was he merely very, very unlucky? In hours of interviews with Durst, research, and even reenactments, the series sought to unravel the mystery.

It was a real-life story, of course, and three women were dead. But it was also terrific entertainment.

When news broke before the finale that Durst had been arrested on a murder charge in New Orleans a day earlier, viewers’ anticipation spiked. The audience for the episode’s first airing, on the East Coast at 8 pm, was nearly double that of the previous week’s episode.

And the spoiler made people really mad, especially evident on Twitter. Barry Jenkins — the director who two years later would win an Oscar for Moonlight — seemed to voice the feelings of many when he tweeted at the Times: “Just deleted your app, much thanks for the SCREAMING spoiler for us west coast fans of HBO’s The Jinx.”

Though it happened in 2015 — not all that long ago — the Jinx kerfuffle embodies what has become the never-ending spoiler wars. We all know generally what a spoiler is: It’s when information about a story is revealed before a person can read or watch it. But the rest of the definition is up for grabs. Is it just an unexpected twist, of the “I see dead people” variety? Is it any mention of plot at all? Is it (as I’ve been told on occasion by tweeters) just a statement of opinion on the quality of a movie? Is it bad? What actually “spoils” someone’s experience of a piece of entertainment? And is anyone actually entitled to not having a piece of entertainment spoiled once it’s out in the world?

In the case of The Jinx, the story was sticky. It was undeniably news that Durst, whose real estate wealth and trail of accusations had long made him fodder for New York tabloids, had been arrested in New Orleans and charged with murder; the fact that it happened while a show was airing about just that matter wasn’t coincidental, but no one could really argue that the news of his arrest should have been marked with a spoiler alert.

But for some, the Times alert (and subsequent alerts and tweets from other outlets) about the documentary’s shocking climax fell into more of a gray area, because it meant the big reveal would no longer come as a surprise as they watched the episode — and it wasn’t as if they went looking for that information. On the other hand, others pointed out, framing the Durst case as entertainment rather than a journalistic investigation was the problem. This wasn’t fiction; it was real life. “The Jinx is a news story. Families are in pain. A psychopath murderer killed 3 women. There’s no spoilers. Sooner everyone knows the better,” journalist Steph Haberman wrote on Twitter.

Oddly, then, The Jinx may have been most successful not at examining its ostensible themes, including how a wealthy man might manage to get away with murder; instead, its lasting legacy is that it became a window into “spoiler culture.”

Which is something that governs my professional life. I’ve been a film critic for many years, and there’s an imperative to not spoil the plot of a movie for the reader. The handwringing over spoilers hasn’t always been part of art; for centuries, theater and literature would announce the plot before the entertainment began, and even as recently as 1976, George Lucas explained the full plot of Star Wars in the New York Times — a year before the movie came out.

But about the time that the internet started to become a force in our lives, “spoiler alerts” became common, fueled by people seeking entertainment coverage online, as a way for writers and fans to warn away people who wanted to experience a movie or TV show without knowing what would happen. As readers and watchers, we want to be able to control our experience of our entertainment. And so spoilerphobia has grown. Now, the threat of spoilers is used as de facto opening weekend box-office boosters: Recently, the Russo brothers somewhat arbitrarily declared a “spoiler ban” on Avengers: Endgame until the Monday after release — a surefire way to ensure people who don’t want the movie spoiled will make an effort to see it before then.

And yet while I warn readers when I’m going to “spoil” the movie, usually in order to be able to analyze it or make a good argument, I prefer just the opposite. I love spoilers. I seek them out.

Something has to be wrong with me.

Or maybe not. Whether spoilers are good or bad depends on who you ask. Critics routinely abide by strict rules set by film studios, agreeing to withhold information about and reviews of movies until a certain date. That implies spoilers are “bad,” ruining viewers’ enjoyment of a movie or show. And studios set those rules to keep potential audiences from deciding they no longer need to see the movie — and thus no longer will be buying a ticket — because why bother if they know what happens?

But for some, spoilers are actually a kind of bait, something they actively seek out. In the case of The Jinx, the Times alert and the news of Durst’s arrest may even have drawn a larger audience, with people eager to see how Durst’s confession played out. And there are entire subreddits devoted to parsing trailers and footage leaks for spoilers or hints of spoilers, for plotlines of upcoming Star Wars and Marvel movies, for the conclusion of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, for what will happen next in Succession. (Before Game of Thrones finished its final season earlier this year, sharing and discussing spoilers online was a beloved pastime for many of the show’s most avid fans.) So, clearly, I’m not alone in liking spoilers, or at least in seeking them out.

I also know that when I reveal a spoiler or an event in an article, readers come running. My review of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood garners good traffic, but my explanation of the ending, published a few hours after the movie started opening in theaters, drew many more eyeballs, in numbers that indicate people want to read about the end before they see the movie.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19307327/23avengers_hp_promo_superJumbo_v3.jpg) Marvel Studios

Marvel StudiosFor me and apparently many others, knowing what’s going to happen in a movie before we see it helps us enjoy the experience more.

Benjamin K. Johnson and Judith E. Rosenbaum are researchers who’ve spent years studying how people react to spoilers. Rosenbaum is an assistant professor of media studies at the University of Maine and Johnson is an assistant professor of advertising at the University of Florida. Together, they’ve authored several papers for peer-reviewed journals about the factors that contribute to a person’s enjoyment of — or hatred for — spoilers.

And there are a lot of factors, from someone’s personality traits and brain-processing speed to how much they need to feel they’re in control. What Johnson and Rosenbaum have found is that why some people love spoilers and others hate them is complicated — maybe as complicated as spoilers themselves. I talked to them about what they’ve learned in their research and what it might mean for me as a spoilerphile and a critic.

(Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length but contains no spoilers … unless you don’t know how the Harry Potter series ended.)

Alissa Wilkinson

So why do I like having movies spoiled for me?

Judith Rosenbaum

I like having things spoiled for me, too! When the last book in the Harry Potter series came out, I flipped to the very end to make sure Ron, Hermione, and Harry all survived.

What Ben and I are finding is that a lot of people’s reactions to spoilers depend on the circumstances. It’s not one-size-fits-all. We’ve published several papers that point to personality traits as a factor, for instance, or even the genre. We’ve found that when comedy is spoiled, it’s less enjoyable. But when fantasy is spoiled, it doesn’t seem to matter as much. Another thing that matters is the medium — whether it’s television or film.

Ben Johnson

One of the things that we found is that it may have to do with some people’s sense of control. Like Judith said, a lot of the effects we find are that small spoilers aren’t quite as powerful as people think they are. But if you give people spoilers and they don’t want them or they’re not expecting them, that can make them feel like they’ve lost control over the viewing experience or the reading experience.

On the other hand — and this is still a speculation because we don’t have much evidence for it yet — people who seek out spoilers may do so because they want to feel as if they’re in control of their experience with the story. People who don’t want to solve the mystery or the puzzle of the narrative but just want to know how it ends, those people are more likely to choose stories that are spoiled.

Also, people who like spoilers tend to be people who don’t like big emotional experiences. They don’t want that anxiety or worry that comes with not knowing what will happen to the characters.

Alissa Wilkinson

You’ve also found that the way a person processes information and emotion has an effect on their spoiler preferences. Is that right?

Judith Rosenbaum

Yes. We found that in some cases, when you try to make sense of a narrative, it takes up a lot of brain power. Research has found that sometimes spoilers can increase what we call “processing fluency,” which means that knowing what’s going to happen ahead of time makes it easier to make sense of the events that are actually taking place in the story. That can increase your enjoyment; if you know what’s going to happen in advance, you maybe have more time to think about what someone’s wearing or what they’re saying, or it lets you pay attention to a joke, for instance. Spoilers can make it easier for you to make sense of what you see.

At the same time, we’ve also found that some people will actively seek out spoilers to protect themselves. So Morgan Ellithorpe and Sarah Brookes, two other researchers, did a study where they looked at the finale of How I Met Your Mother. They found that people who knew [ahead of time] what happened at the end were less stressed out while watching the finale.

Then we did a follow-up, where we found that when people are very concerned about characters, they’ll actually actively seek out a spoiler because they’re like, “Oh, my gosh. I want to know what’s going to happen to this person.” It eases their mind. This is still speculation, but it may give them a little bit of a sense of control — “Okay, I know how this is going to turn out. Nothing’s going to freak me out.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19307141/GettyImages_51096792.jpg) Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlissa Wilkinson

I certainly feel that way. And I know other people do too, because people seem to search the internet quite avidly for articles that reveal spoilers. As vocal as spoiler-haters are, there are a whole lot of spoiler-lovers out there, too.

Ben Johnson

That’s what we’re thinking about right now, in fact: Who seeks out spoilers and who doesn’t. In the past, we’ve researched whether spoilers are “harmful,” whether they ruin people’s enjoyment, their sense of being “in” the movie as it’s happening. We don’t find a lot of evidence that they do. We see tiny effects, or no effects, that suggest the “spoiler” problem is a myth — at least in changing the way you engage with the story.

But people believe in that myth! So people approach spoilers differently. Some are going to try really hard to avoid spoilers. They might change when they’re going to see a film or whether they’ll even see a film at all, based on a spoiler.

Alissa Wilkinson

So, many people may not naturally have much of an opinion about spoilers, but they’ve been conditioned to react to them by people who hate them. Is that what you’re saying?

Judith Rosenbaum

Yes.

Ben Johnson

I would agree with that.

One thing that comes up a lot is the question of why people get so worked up about spoilers and why this has become such a big thing in the last five to 10 years. A lot of it is because the environment around media consumption has changed so we’re talking more to each other online about content. There are more reviews, and they’re more accessible. If I go into my social media news feed now, I’m seeing spoilers or reviews from TV shows that aired last night.

But people are also consuming content at different times. We’re not all watching the programs at the same exact time. It’s always been that way for film, but now television is on-demand too. So that’s led to the idea that people are worried about spoilers and a culture that’s developed around it.

A lot of our findings show that people [who fear being spoiled] are overly anxious, because spoilers aren’t as powerful as people think they are. But at least we’ve developed these norms online where people will try to be respectful of each other and try to give spoiler warnings and things like that. So there are some positive aspects as well, even if maybe there is still this sort of myth that spoilers are all-powerful.

Judith Rosenbaum

People are notoriously bad at predicting how much a spoiler will affect them. They assign a lot of weight to knowing the outcome of a plot, whereas a lot of our enjoyment actually can come from just the process — not knowing that Ron, Harry, and Hermione beat Voldemort but knowing how they did it. We are not very good at figuring out what we like and what we don’t like, sometimes.

Alissa Wilkinson

Earlier, you mentioned genre. How does the genre of a work connect to all of this?

Ben Johnson

In our most recent study, we studied horror films, and what we’ve found has been interesting. For some people, when they’re watching horror films, they want to know that a little scare is coming: Someone’s about to be harmed or something scary is about to happen. Music is an important cue for that as well. If they knew something was coming, they enjoyed it more because it produced a feeling of [cathartic] anxiety. Maybe you don’t want that anxiety when you’re reading or watching Harry Potter, but if you’re watching a horror film, you kind of want that anxiety. It depends on what people are looking for from different types of stories.

Judith Rosenbaum

In comedy, if you ruin the punchline of a joke, obviously it’s not funny anymore. That’s what we’ve found: When you spoil comedy for people, they just don’t enjoy it as much.

Alissa Wilkinson

You also mentioned that spoilers can help people make better sense of a story. Can you expand on that? I’m not really a person who processes information slowly, but I somehow still have a very hard time remembering the plot of a film. Like, I’ll see a movie, and I can tell you what the premise is, but I couldn’t tell you how the plot progressed.

As a critic, I have to be able to remember plot. So having a film spoiled ahead of time makes it possible for me to actually watch it as a movie, looking at the visuals and thinking about the dialogue and acting and all of those things, instead of just frantically trying to scribble down every detail of what’s happening.

Judith Rosenbaum

That perfectly ties back to what other researchers have found about how spoilers can increase “processing fluency.” [Once you’ve been spoiled], you get the chance to make sense of the rest of the story.

But other research has disputed that finding. Which means that [knowing spoilers] works well for some people and not for others.

It might depend also on why you’re watching the movie, what your purpose is. If you’re watching it for work or for class, clearly you have a different mindset than when you’re just chilling out on the couch and you want to be scared and curl up under your blanket.

Alissa Wilkinson

Is there any way to test for how much a person wants or needs to be able to control their experience? Like would you be able to measure that and other characteristics in me and put me on some kind of scale relative to other people?

Ben Johnson

We looked at something called reactance, which is when you feel like your control’s been taken away. It has to do with if I get angry or I get frustrated because you told me I can’t do a certain thing — or in this case, because you spoiled a movie for me that I didn’t want spoiled — then I am feeling a lot of reactance. We studied that trait and people’s responses to spoilers, and we found reactance played a little bit of a role and that people feel higher reactance when they’re spoiled [against their will].

We’re planning a future study where we’re looking at self-control and the role that plays, too.

Alissa Wilkinson

Do you mean kind of like the marshmallow test — people who can’t help but spoil themselves even if they know they’ll be happier if they don’t?

Ben Johnson

Yeah, it’s similar to that: people being impulsive and thinking, “I want the spoiler now and I can’t control myself.”

Judith Rosenbaum

And then we want to look at how that interacts with certain situational factors. Like, do you have less self-control when you’re tired? I think we all know that eating the chocolate bar when we’re really tired just seems to happen more naturally. The same might apply to spoilers, right? Does our self-control go down when we’re just not on top of our game as much?

People are able to control when they watch a movie or show and how they watch it. So they also want total control over what they know about the movie going in. I think that sense of control has become a lot more pervasive just in the last decade alone. I think we all remember the Simpsons episode where Homer Simpson walks by the line of people waiting to get into the second Star Wars movie and says, “Huh, who knew? Darth Vader was Luke’s father.” That stuff is happening all the time, but we’re in an environment now where we feel like we control what we see and when we see it, and who we hear from and at what time, by setting up our social media algorithms. Spoilers kind of cut across all of that. They take that control away.

Alissa Wilkinson is Vox’s film critic. She’s been writing about film and culture since 2006.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More