It’s not what you think.

Last Thursday, the Associated Press reported that more than 40 US Army reservists and recruits who had been promised a path to citizenship when they joined the military had been “abruptly discharged” without being told why.

The AP report, which came in the wake of the family separation crisis at the US-Mexico border, sent shockwaves through social media. People of all political stripes condemned the Pentagon’s actions as disgraceful, un-American, and a betrayal of our troops.

Former Obama National Security Adviser Susan Rice denounced it as “outrageous and shameful” on Twitter. President Donald Trump’s former White House communications director Anthony Scaramucci tweeted out the story, saying, “America was built by immigrants willing to fight for freedom. We must not lose sight of our founding values.”

But while the report attracted lots of eyeballs, this is actually an issue that dates back to the last months of the Obama administration. And it’s not yet clear whether Trump’s tough anti-immigrant stance is what’s driving the removal of noncitizens from the US military.

Here’s what you need to know about what’s going on, and why it’s sparking such a huge controversy.

The defunct military program used to recruit noncitizen troops, explained

Back in 2009, the Pentagon launched a new pilot program to allow thousands of foreign-born recruits, particularly those with medical skills or fluency in a critical foreign language, to join the US military. In exchange, these recruits would be put on a fast-track to US citizenship for their efforts.

The program, called “Military Accessions Vital to National Interest,” or MAVNI, for short, was designed to attract people with skills that could help the US better interact with people who speak uncommon languages, or even provide dental care, for example. Around 10,400 immigrant recruits entered the military through that program over the past nine years.

Obama also allowed hundreds of participants in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program to go through this process. However, a Pentagon spokesperson tells me the military wasn’t looking to recruit Spanish speakers, as it was not a major language need.

But then in September 2016, Obama froze MAVNI over national security concerns. The Pentagon worried that some recruits could potentially have connections to terrorist organizations or foreign spy agencies. Recruits were also booted out during the Obama years.

The Pentagon wouldn’t confirm or deny that the military had accidentally brought in a person or persons who fit that description, but Maj. Carla Gleason, a Pentagon spokesperson, told me “there were multiple security concerns” with the recruitment process back in 2016. “The program had unacceptable levels of risks that we couldn’t mitigate,” she continued.

The Defense Department extended the program for one year as background checks proceeded, but the Trump administration didn’t renew the extension 12 months later. That means, as of now, the MAVNI program no longer exists.

But here’s the thing: The Pentagon still conducts background checks for recruits who applied before the program ended. As of now, there are around 1,100 people still waiting to hear if they passed a background check — and many are not being accepted for one main reason.

This is likely an administrative issue, not a xenophobic one

Background checks are routine for anyone hoping to join the government in any capacity. The military, of course, is no exception.

It can even take a while for US citizens to get through the process. “It took me two and a half years to get a security clearance and I’m from the United States,” says Maj. Gleason.

Here’s just one example of how long it can take for immigrants hoping to enter the US military: Charles Choi, who is originally from South Korea and wanted to join the Army reserves, has had to wait for about two years for his completed background check. When Military.com reported on the story in April, he had yet to go to basic combat training.

That of course causes a backlog — and also a bigger problem. As Military Times pointed out on July 7, recruits must go to basic training within three years of signing their contract. If the background check process takes longer than that, then they’re discharged from service.

And it’s much more complicated to conclude those investigations if someone comes from abroad. Most MAVNI recruits hail from Africa or Asia, and it’s hard to get all the necessary details about someone’s life from certain governments that don’t reliably keep official records.

That may explain why on October 13, 2017, Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis issued a memo that told the Pentagon to more vet MAVNI applicants more carefully.

Let’s be clear: Bringing someone into the ranks of the military from a country with powerful terrorist organizations, for example, would obviously be a risk the Pentagon takes seriously. If the military can’t guarantee someone has zero ties to terrorists, then the recruit would likely not stay in a US military uniform.

Why some immigrant recruits now have to leave the military

In some instances, noncitizen recruits could join the military for basic training, an unnamed Army recruiter told Task & Purpose on July 6.

That’s not out of the ordinary. Some troops take an oath of service even before a completed background check, which means “you belong to the military … But you’re not technically in the military,” John Noonan, a defense policy adviser to Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) who was formerly in the Air Force, tweeted last Friday.

So some MAVNI troops were already participating in military activities when they found out that they didn’t pass the background check. Those recruits were booted out of uniform.

However, some applicants were never given a reason why they couldn’t serve anymore.

Here’s one such instance: After a foreign national to came to the United States to attend Texas A&M University in July 2009, he chose to enlist in the US Army in February 2016.

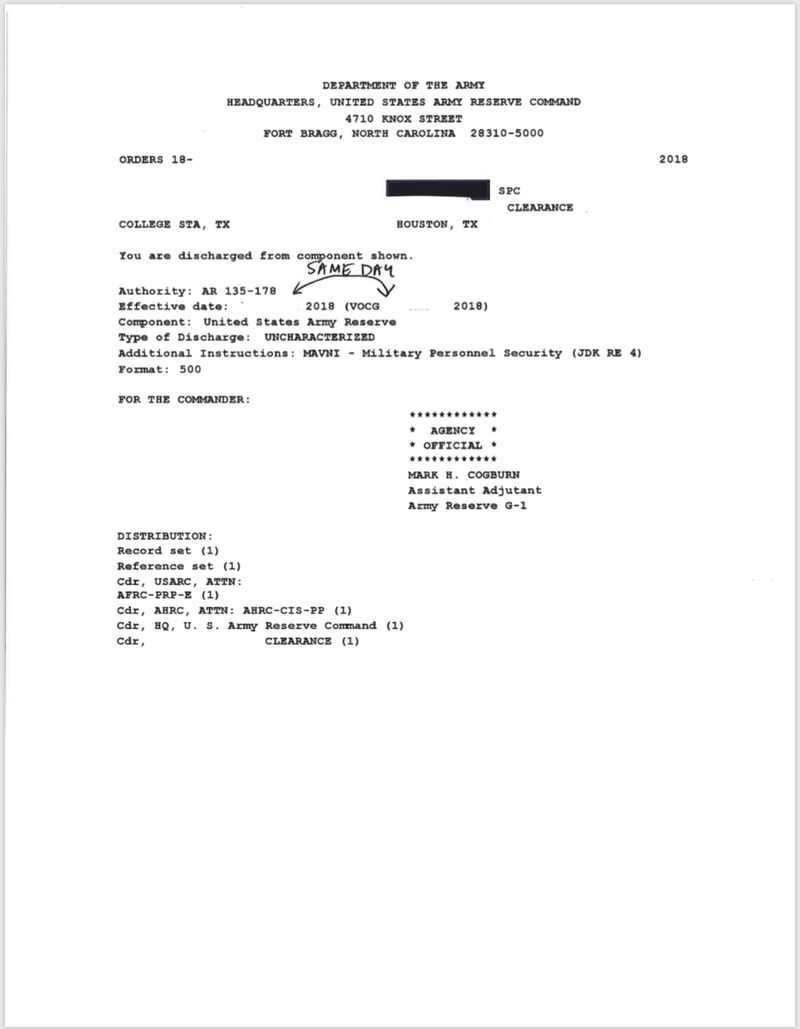

But after a couple of years in uniform, the man received a letter from the Army Reserve notifying him he could no longer serve in the military, though the reason wasn’t given. The Pentagon has yet to tell the now-former soldier, whose name Vox is withholding so as not to identify him during a sensitive time, why he can no longer serve.

In the paper below, note that the type of discharge he received was labeled “uncharacterized” in capital letters.

The Army didn’t immediately respond to a Vox request to explain what might prompt an “uncharacterized” discharge.

But according to an unnamed Army recruiter who spoke to Task & Purpose, it’s rare for someone to leave the military without really knowing why.

“I don’t doubt that there were some piece of shit recruiters that shit-canned these kids for the sake of it,” that official told reporter Jeff Schogol. “But in my office, we sat down individually with every one of them and laid it all out — what it meant — and asked them if they wanted to continue.”

But some legal advocates for the MAVNI recruits, like immigration lawyer and former soldier Margaret Stock, think the Defense Department owes all discharged recruits an explanation. “We don’t know why the Pentagon is doing this because they won’t say why,” she told me. “You just can’t function as a military this way.”

Stock, who also created the MAVNI program, argues the Pentagon purposefully wants to keep these troops out, and to do so is suppressing information that lauds the MAVNI program.

According to an unreleased 2017 report by RAND Corporation, a Pentagon-supported think tank, MAVNI recruits perform better than most others, especially in performance and promotions. The program also “has been a cost-effective recruiting program for the Army,” the report says. Stock and other critics claim the Pentagon is suppressing the report’s public release because it makes the MAVNI program look good.

The Pentagon disputes that account. “The report does make MAVNI program look good,” Maj. Gleason told me, “but that’s because the report is unclassified. All the risks to the program are classified.”

But ultimately, what this means is that many of the thousand-plus recruits still waiting on their background check results may have to leave the military soon.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png