The alternative universe of the Democratic primary cracked, but just briefly.

The Democratic presidential debates, like all presidential debates, have mostly taken place in an alternative universe where the president’s powers are absolute, and so the argument revolves entirely around electability, differences between the proposed agendas of the candidates running to win the White House, and decades-old votes that supposedly reveal their true values.

But at Tuesday’s South Carolina debate, the reality of the situation the next president will face occasionally broke through, though never very clearly, nor for very long.

Every Democratic candidate running for president is proposing a sweeping legislative agenda, which means the actual constraint, if any of them win, is how many votes Democrats have in the House and Senate versus how many they need.

In the House, that answer is straightforward: 218, or a bare majority of the chamber’s 435 seats. In the Senate, the answer is more complex: They need 50 votes to take control, but 60 to pass most legislation, due to the omnipresence of the filibuster. There are some exceptions to that rule — the budget reconciliation process permits some legislation, under narrow conditions, to pass with 51 votes, and judicial nominees are now immune from filibuster — but in the Senate as it’s currently composed, 60 votes is usually the necessary number.

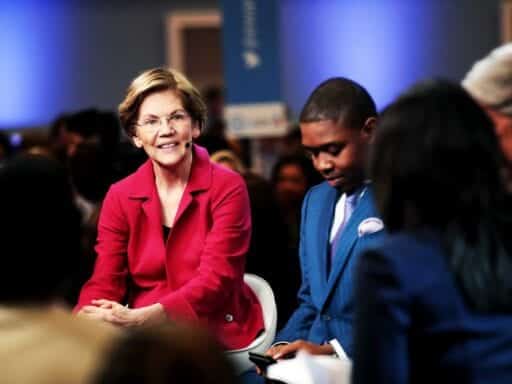

Sen. Elizabeth Warren tried to force a conversation over that 60-vote limit tonight. It came during a conversation on gun control, wherein former Vice President Joe Biden bragged about beating the NRA in the ’90s, and said he’d do it again as president. What he didn’t mention is that the Obama administration repeatedly sought, and failed, to pass gun control in the aftermath of horrific mass shootings. Biden was part of that effort, and he was unsuccessful. It fell to Warren to explain why:

We have to talk about what it’s really going to take to get something done. I’ve been in the Senate. What I’ve seen is gun safety legislation introduced, get a majority, and then doesn’t pass because of the filibuster. Understand this: The filibuster is giving a veto to the gun industry. It gives a veto to the oil industry. It’s going to give a veto on immigration. Until we’re willing to dig in and say that if Mitch McConnell is going to do to the next Democratic president what he did to President Obama, and that is try to block every single thing he does, that we are willing to roll back the filibuster, go with the majority vote, and do what needs to be done for the American people. Understand this: Many people on this stage do not support rolling back the filibuster. Until we’re ready to do that, we won’t have change.

Warren is right, on all counts. Among those who oppose rolling back the filibuster are Biden, and Sens. Bernie Sanders and Amy Klobuchar. But Sanders got the next question, and he ignored the issue, spending his time apologizing, instead, for past votes to grant gun manufacturers immunity from lawsuits.

Former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg tried to press the point a few minutes later, saying:

I want to come back to the question of the filibuster because this is not some long-ago bad vote that Bernie Sanders took. This is a current bad position that Bernie Sanders holds. And we’re in South Carolina. How are we going to deliver a revolution if you won’t even support a rule change?

Sanders got the next word and, again, ignored the issue, choosing instead to highlight a commendation he got from a gun control organization started by former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg.

The tension between Sanders’s revolutionary rhetoric and his more institutionalist approach to Senate rules is underexplored in his candidacy, but would be a serious problem for his presidency. The only place he has sought to resolve it is Medicare-for-all, where he’s offered a complex plan to use the budget reconciliation process by instructing his vice president to try and overturn the Senate parliamentarian’s rulings, but since budget reconciliation is limited to a single bill a year, that doesn’t answer the question for the rest of his agenda.

Senate Democrats can’t change the filibuster — indeed, they’ll be trying to wield the filibuster — if they don’t win back the Senate, so Tuesday night’s other occasional moment of clarity came as various Democrats argued for why they were the best choice to lead a ticket that could win it.

Klobuchar argued that “the way we do it is having someone leading the ticket from a part of the country where we actually need the votes,” gesturing toward her success winning elections in a purple, Midwestern state. Joe Biden noted that he campaigned for most of the House Democrats who won Republican seats in 2018, and has endorsements from more of them than any other candidate. Bloomberg argued that he’d spent more than $100 million to help elect those Democrats, and in a moment of honest, but infelicitous, phrasing, said, “I bought them,” and then corrected himself to “got them”:

Did Mike Bloomberg actually just tell the Moderators that he BOUGHT all the Dems who voted in Nancy Pelosi for $100 million?

What is happening in this #DemDebate2020 right now?#democraticdebates pic.twitter.com/1mY3oXsZGI

— Big Dan Rodimer for Congress-Nevada’s 3rd District (@DanRodimer) February 26, 2020

But here, again, both the moderators and the candidates quickly moved on.

Every Democratic debate so far has featured a lengthy argument over the details of Medicare plans that the next president will have limited, and if there’s a Republican Senate, no power to pass. None have featured a sustained debate over the questions that will actually decide what kind of Medicare plan — and climate plan, and gun control plan, and minimum wage bill, and infrastructure plan — will pass: which candidate is likeliest to sweep more Democrats into the Senate, and whether and how the various candidates would convince Senate Democrats to change the rules to make ambitious governance possible again.

We’re deep into the primary now. There have been 10 Democratic debates (12 if you count the debates broken into two nights), and even more forums, town halls, and so on. We know, at this point, what the candidates want to do. It’s time for debate moderators to start pressing them, in a serious and sustained way, on how they’ll do it.

Author: Ezra Klein

Read More