Doctors need mental health support, but the medical profession often punishes them for getting it.

This story is part of The Aftermath, a Vox series about the collateral health effects of the Covid-19 pandemic in communities around the US. This series is supported in part by the NIHCM Foundation.

Last August, Dr. Scott Jolley came home at 3 am from a busy emergency room shift looking pale, far older than his 55 years. It was the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, and he had been the only physician on duty at his hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. One of his patients had gone into cardiac arrest after Jolley removed his personal protective equipment to meet his next patient. Jolley, athletic with dusty brown hair, had to frantically gown up and run back to perform a resuscitation. The patient survived, but Jolley felt agitated.

When Jolley’s wife, Jackie, woke up at 6, she found him at their kitchen table, hunched over and unable to sleep. He was worrying that in his hurry, he hadn’t put on his PPE correctly, that he might expose Jackie and their three daughters to the coronavirus. He was also mortified about what he’d muttered to himself as he left the patient’s room: “I can’t take this anymore; this is not good for me.”

Jackie wasn’t used to seeing her husband in distress. His friends called him “the patriarch.” He was the one everyone else turned to: the kind of guy who talked his way into the ICU to support his daughter after a birth complication, who organized an elaborate fly-fishing trip for the birthday of a friend’s child. Over his 28 years as a doctor, Jolley brought the same attention to detail and compassion to thousands of patients who came into his ER.

But as he settled into his 50s, the pace and pressure of the job became unbearable. He began having conflicts with colleagues, who at one point organized a meeting to request Jolley get his anger under control. In 2018, Jolley started thinking about a path to retirement and repeatedly asked his managers at Utah Emergency Physicians — a physician group that contracts with hospitals in the Intermountain Healthcare system, where he worked — for ways to wind down his schedule.

With the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic, however, Jolley had to speed up. He was often given evening shifts — usually the busiest in the ER — and because of pandemic cutbacks, he was the only doctor on duty. Having to don and doff new PPE with every patient, and do it quickly enough to keep up with the chaos of a pandemic ER, “made every shift, and every hour, a lot more stressful than even it had been before,” Myles Greenberg, his best friend and a former ER doctor, says.

When Jolley reached out to the head of his department to ask for advice on managing pandemic stresses, Greenberg recalls Jolley telling him, “She said something like, ‘I just wait until it’s over.’ It was like, grin and bear it,” an attitude that reflects the “macho culture of emergency medicine,” he adds.

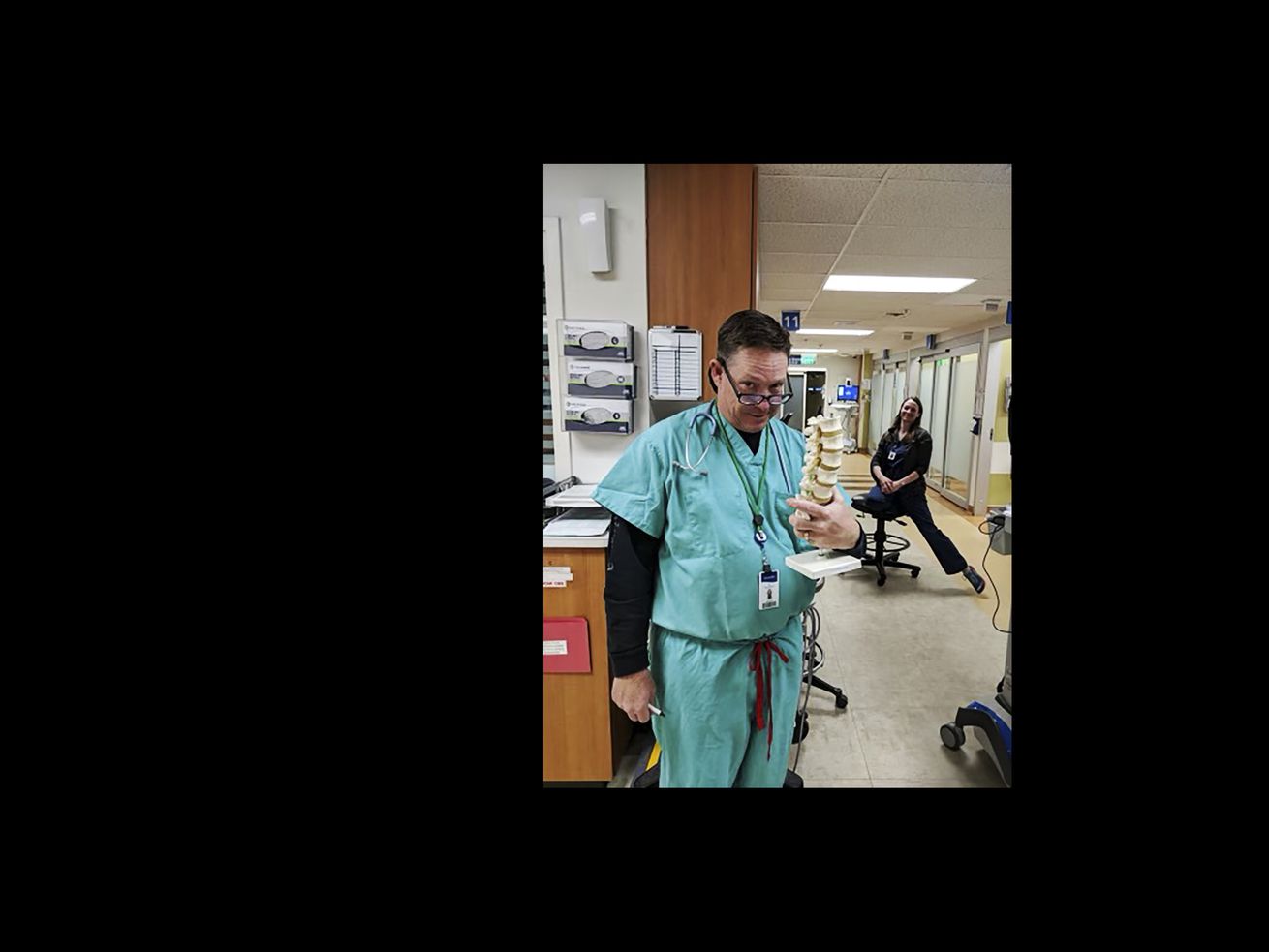

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22660044/IMG_2455_copy.jpg) Courtesy of the Jolley family

Courtesy of the Jolley family/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22658499/IMG_0483.jpg) Courtesy of the Jolley family

Courtesy of the Jolley familyBy August, Utah Emergency Physicians had denied Jolley’s requests for another doctor to support his shifts, and did not offer him a pre-retirement schedule because he wasn’t yet 60. (UEP told Vox that the company was looking into pre-retirement options at the time.) He felt he had no other choice but to take an unpaid sabbatical, Jackie recalls, and he planned to use the time to explore his options and “get his mental health back in order.”

During his time off, a new stressor emerged: “He was very, very worried about losing his license and credentials,” his wife says.

Medicine is, ironically, a profession that punishes some doctors for getting mental health care. Many physicians work under intense pressure and are exposed to trauma on the job. A worrying number of doctors die by suicide each year. Yet structural barriers — enforced in part by medical boards and hospital systems — frequently discourage doctors from accessing care that could save their lives.

One of those barriers is a fear of what can happen to doctors who receive treatment. In dozens of states, medical boards ask physicians sweeping questions about their health histories that would require them to disclose a diagnosis or treatment for mental illness. Similar questions come up when doctors apply for hospital credentials or insurance reimbursements. A disclosure can trigger a call to appear before the state board, a demand for medical records, or even a psychiatric evaluation. In the worst cases, doctors may be restricted in how they practice medicine or even lose their licenses.

Even though Utah’s state medical board doesn’t require mental health disclosures, Jolley worried that any support he received during his sabbatical could jeopardize his career and impact his family’s livelihood, Jackie says. He made her promise she’d keep his struggles a secret, even from Greenberg.

By November, Jolley — who had no history of mental illness prior to the pandemic — was diagnosed with PTSD. He was put on a regimen of medicines to treat depression and anxiety and improve his sleep. They seemed to help a little, Jackie recalls, but soon he became more fatigued and agitated. That was the first time Jackie heard him talking about how he could end his life.

Halfway through his sabbatical, on February 5, 2021, Jolley attempted suicide. That evening, he was admitted to the psychiatric unit at his own hospital, the same place he’d sent dozens of his emergency room patients over the years. Being cared for by the colleagues from whom he wanted to conceal his mental health condition was a new, immense source of stress and shame, his wife remembers. But he was one of many US health care workers whose insurance would only cover treatment within the system where he worked.

The lights were kept on in Jolley’s room and he had no door, so other patients wandered in and out at all hours, Jackie says. The clothes he was wearing when he arrived were deemed risky by the hospital, so he was given a baggy shirt and pants left behind by another patient, according to Jackie.

After two days, he was discharged from the hospital.

Less than two weeks later, on February 19, he killed himself at home.

Jolley’s family and Greenberg are now convinced that the medical profession failed a doctor who dedicated his life to saving the lives of others. They say the stigma and fear of punishment for seeking mental health care delayed his treatment, then added stress in his most vulnerable moments. Jolley asked the management at his physician group for help at least five times in writing between March and August 2020, according to emails obtained by Vox. Jackie and Greenberg say there were additional phone calls, conversations, and emails.

“They had a business to run and wanted to survive the pandemic and didn’t recognize Scott was reaching out for help,” Jackie says. “He told me they all thought he was just an old, angry doctor.”

In an interview, Dr. David Barnes, the president of Utah Emergency Physicians, told Vox that the experience with Jolley has caused his group to learn that “people can be struggling without it being obvious or apparent on the surface.”

“We recognize emergency medicine is a difficult specialty and can take its toll on physicians of all ages,” he added. “We need to look at ways to support our aging physicians so they can have a satisfying exit to their career.”

Intermountain Healthcare, the hospital system where Jolley and his colleagues worked, said in a statement: “The loss of a colleague is sad and heartfelt in every circumstance, and our thoughts are with his family and friends.”

The need to support doctors and address the mental health toll on the health workforce has never been greater. Vox spoke to more than two dozen colleagues, family members, and friends of physicians who died by or attempted suicide, as well as physicians who attempted or contemplated suicide. They said the pandemic has laid bare an inhumane health system that sacrifices the mental health of the medical workers who keep it going. They also spoke of a mental health crisis in medicine that long predates the arrival of the coronavirus — one that could worsen in the pandemic’s aftermath.

An “occupational hazard”

One warning sign of the disproportionate stresses on health workers over the past year and a half emerged in April 2020, when a New York City emergency room physician, Lorna Breen, died by suicide. Her family still doesn’t know who alerted the press, but Breen’s story was made public without their consent. “Once it was out there we decided to lean into the conversation, to tell the world what happened, because we believe Lorna’s death could have been avoided,” her brother-in-law, Corey Feist, told Vox. “The more we told the story, the more we heard from others throughout the country, and the world, who had similar experiences.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22658534/IMG_2123_copy.jpg) Courtesy of Corey Feist

Courtesy of Corey FeistLong before Breen’s death, suicide was known within the medical field as an occupational hazard. One recent study, based on five years of CDC data from 27 states, estimated that an average of 119 doctors take their own lives in the US each year. That number is comparable to the suicide rate in the general population, but it’s likely an undercount, says Dr. Katherine Gold, the lead author on the study and an associate professor at the University of Michigan Medical School. The toll could be as large as 300 to 400 deaths per year — according to an oft-cited estimate — roughly double the suicide rate in the general population.

Such a high risk is especially troubling in physicians, Gold pointed out, because they “have access to health care and the health system, and understand mental illness and that [it] is a treatable disorder — and we’re still seeing rates that are [at least] as high as the general population.”

Physicians are more likely to experience depression than the general population. The problems emerge in the high-stress years of medical school, and by the start of residency — when doctors’ DNA was found to age six times faster than that of their non-physician peers — rates of depression increase fourfold in the first four months. Across all residency programs, an average of one-third of doctors meet the diagnostic criteria for major depression. Suicide was the second most common cause of death after cancer among these newly minted doctors between 2004 and 2014. A second peak in suicide risk occurs in late middle age, according to one analysis.

These phenomena are often referred to as burnout, but that’s arguably “a misnomer for what’s happening,” says Oregon family doctor and mental health activist Pamela Wible. “It severely minimizes and blames the victim for the situation.”

Wible began studying physician suicide in 2012, after three of her colleagues died by suicide in the span of 18 months. She has found more than 1,600 deaths in the ensuing nine years, and her analysis reveals systemic contributors to mental health problems “that are the norm in medical training and practice, and this is pre-pandemic,” she says. The pandemic was like “the icing on the cake,” she adds. “What most people are suffering from goes far beyond this pandemic.”

During training, many doctors work shifts that exceed 24 hours, and in some specialties — including emergency medicine, surgery, obstetrics, and critical care — the grueling hours and sleep deprivation continue after residency. Several doctors told Vox that they don’t have time or convenient locations to eat and drink while on their shifts.

Doctors and nurses also routinely treat patients in understaffed units, and because of business decisions in their health systems and gaps in patients’ access to medical insurance, they often can’t deliver the care they want to and feel they should. “Our moral compass is incredibly compromised by the systemic barriers in the US that have made it about the bottom line rather than what we can do for patients,” says Mona Masood, a Philadelphia psychiatrist who has been treating doctors in crisis over the past year.

Many of the problems have been allowed to fester, Wible says, because half of US doctors are employed as independent contractors and aren’t protected by many labor laws. Other industries, such as “the airline industry, police, firefighters,” have more stringent protections and “value their workers” more, she argues, adding that even her pet groomer is not allowed to work an eight-hour shift without breaks under Oregon labor law.

The structural contributors to mental illness and physician suicide are layered on top of the potentially vulnerable psychology of doctors. Medicine attracts people who may be at higher risk for mental health problems, Masood says: high-achieving perfectionists who put tremendous pressure on themselves to succeed and help their patients. “To be a doctor, not only do you have to be intelligent in the subject matter, but you have to be the best of everyone, have all the answers,” she explained. “You are applauded and given so much positive feedback when you self-sacrifice.”

That psychology has led to another paradox: Despite strong evidence about the importance of treating mental health issues, “there’s a tremendous stigma in medicine to getting help, to asking for help, to admitting you have at all suffered,” says Jessi Gold, a Washington University psychiatrist who specializes in treating health workers. “Emotions, struggling, are an imperfection, and medicine is a field of perfection.”

Untreated physician depression and burnout has been consistently linked with a higher risk of medical errors, poor patient safety, and, for doctors, a risk of suicide. It’s not yet clear how Covid-19 has affected the physician suicide rate. Though the rate in the general population declined in the early months of the pandemic, many mental health indicators in health workers show worrying signs.

A Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that six in 10 health workers reported pandemic stress had harmed their mental health, three in 10 had considered leaving health care, and more than 50 percent said they are burned out. Research on US emergency department health workers uncovered levels of exhaustion and burnout increasing during Covid-19, with as many as one-fifth at risk for PTSD. These findings echo studies done during the pandemic from China, Canada, Italy, and other countries.

In the midst of the pandemic crisis, Masood created the Physician Support Line, a suicide hotline for doctors that protects their privacy. She says her service has been met with an explosive demand: They’ve fielded more than 2,500 calls from doctors over the past year. Wible runs another helpline for doctors who experience suicidality, and says demand increased so much during the pandemic that she started offering group Zoom calls.

Now that Covid-19 vaccines are rolling out and the stresses of the pandemic are easing in the US, many people want to move on. But Masood worries about doctors who might be unable to, and who may feel they have nowhere to turn. Over the past year and a half, she says, many of her colleagues have expressed some version of the same sentiment: “We felt we were left to die.”

“How am I going to come back from this?”

Like Scott Jolley’s family, the family of Lorna Breen, the New York doctor who took her own life in April 2020, says she had no history of mental illness. But Breen was a perfectionist who lived and worked in a pressure-cooker environment that didn’t allow her space to recover after she got sick in the pandemic.

When she wasn’t directing the busy emergency room at NewYork-Presbyterian’s Allen Hospital in New York City, she was playing the cello semi-professionally, training for marathons, and studying for an MBA. On March 13, the 49-year-old worked her first coronavirus shift. Five days later, she came down with a fever and later tested positive for Covid-19 — then worked through her illness remotely.

On April 5, she returned to work — a lineup of nine 12-hour shifts for the month, according to her hospital. But at a moment when the city’s death rate was exploding to six times its usual level, and the hospital’s capacity was stretched thin, the 12-hour shifts lasted 18 hours, Feist says.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22658621/IMG_2116_copy.jpg) Courtesy of Corey Feist

Courtesy of Corey FeistMore than her own health and recovery, she was worried about her patients, and how any failure to care for them was going to impact her career, says her brother-in-law Corey Feist. “She started to articulate over the course of the week she was back that people were starting to notice she couldn’t keep up, and this was going to be a career limiter,” he recalls. Yet she was “depleted from being very sick,” he says, and working unthinkably hard.

By April 9, she was “nearly catatonic,” unable to stand up from her chair, according to her sister Jennifer Feist. The family reached out to Breen’s boss, Angela Mills, the chief of emergency medicine services at NewYork-Presbyterian, to check in on Breen at her apartment. Mills says she found Breen sitting on a small bench in her doorway, hunched in a fetal-like position, with a scarf wrapped around her.

“She was having a hard time making eye contact, and wasn’t speaking very much,” Mills recalls. She says Breen managed to repeatedly articulate her worry about whether she’d be allowed to work again. “She made a couple of comments about, ‘I’m not going to be able to come back from this. How am I going to face people?’” Mills tried to reassure her while waiting for another of Breen’s friends to arrive.

The Feists arranged to have Breen driven from New York to their home in Virginia. When Breen reached her family, they could hardly recognize her. “Her eyes were dull and she seemed dazed. Her entire affect was different. She was slow moving, slow speaking,” Corey Feist recalls. “She could not answer simple questions about whether she was hungry or not, which fast food restaurant she wanted to stop at.” Her family speculates the coronavirus may have affected Breen’s brain function, but they’re convinced that her work stress, and her concern that mental health problems would derail her medical practice, contributed to her suicide the next month.

“She had enough cognition to realize — particularly once she was admitted to the University of Virginia psychiatric unit — that there’s a stigma on getting mental health care for physicians,” Corey Feist says, “such that it can impact your medical license and your ability to be a physician.

A “hidden curriculum”

Medical boards in 37 US states and territories ask some type of question that could require a doctor to disclose mental health conditions or treatment, according to a recent analysis published in JAMA. In the most intrusive states, the questions are sweeping. Wyoming asks: Have you “ever shown signs of any behavioral, drug or alcohol problems?” Or in Idaho: “Have you been diagnosed and/or treated for any mental, physical, or cognitive condition including substance use disorder that may affect your ability to practice medicine with reasonable skill and safety?”

Doctors also waive their medical privacy rights, particularly when it comes to mental health conditions, to the boards that regulate them. Nearly 40 percent of physicians reported being reluctant to get care or treatment for a mental health condition because of medical license repercussions, according to a survey published in 2017 in Mayo Clinic Proceedings. In another survey of women physicians, half said they believed they had a mental illness but had not sought care, in part for fear of licensing boards.

Even if state regulators omitted all mental health questions, as 17 US states currently do, they can still probe doctors’ mental health histories in other ways, according to Ariel Brown, who co-authored the recent JAMA analysis. “A board may call the applicant in for an interview to explain anything they find fishy,” says Brown, a founder of the Emotional PPE Project, a nonprofit that connects health workers with no-cost and confidential therapy.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22672576/yZ9RR_in_33_states_license_boards_are_asking_doctors_about_their_mental_health.png) Tim Ryan Williams/Vox

Tim Ryan Williams/VoxHospital credentialing — the process used to vet providers who work in hospitals — may be even more intrusive, says Amanda Kingston, a psychiatrist and assistant professor at the University of Missouri who has been studying physician suicide. A HIPAA waiver, granting an institution access to a doctor’s health records, has become a common part of hospital credentialing packages. “Many end up signing it because it’s part of a 40-page packet they are trying to get through to start their job. But even if they’re paying close attention, there’s the concern if they don’t [sign], there might be a suspicion about why,” she says.

For years, a broad coalition of medical groups and health advocates, including the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association, have called on states to stop punishing doctors for seeking help. They argue that regulators should only inquire about mental illnesses that currently impair a doctor’s ability to safely practice medicine, or even abolish mental health questions altogether. Overly broad questions, reformers argue, can discourage physicians from getting support and may violate the Americans With Disabilities Act.

Slowly, state policies are changing. The Medical Board of California, for example, used to ask for a full mental health history, but acknowledged in a statement to Vox that its old policy “may have discouraged physicians from seeking needed treatment.” The board said that in response to feedback, it has shifted the focus of mental health inquiries to current impairments only.

But in many corners of the country and the health care system, broader questions persist. “State medical boards are worried that they could be liable if they remove the questions and something happens,” says the University of Michigan’s Katherine Gold. And unlike lawyers, doctors have mounted few legal challenges against the practice. She doesn’t know of any data showing these questions make patients safer, “and we certainly have anecdotal data that asking these questions prevents physicians seeking care.”

Most of the physicians Vox talked to for this story said they’ve avoided getting mental health care, gone out of state for treatment, or paid out of pocket to avoid billing their health insurer. Kingston says that in the past few months, she’s heard from several colleagues who prescribed their own antidepressants or wrote prescriptions for colleagues, then paid cash for them so there’s no electronic record or billing trail. Jessi Gold, the Washington University psychiatrist, said she routinely gets requests not to document sessions, or to use paper charts that won’t show up in electronic medical records.

Even in places that are more permissive of doctors who have been diagnosed with or treated for mental illness, confusion and fear about licensing issues runs deep enough to drive problems underground. “It’s part of the ‘hidden curriculum’ of medicine that licensing applications ask about mental health, and that can affect you,” Jessi Gold adds.

Lorna Breen may not have been aware that her state licensing board does not ask questions that would require a mental health disclosure. Still, she believed her career was in jeopardy when her mental health faltered, her family told Vox. “Lorna said, ‘I’m going to lose my license,’” Feist recalls. “‘I’m never going to be able to practice medicine again.’ What’s increasingly tragic about the fact she was wrong — and she wasn’t wrong about a lot of things — this is such an ingrained concept for doctors.”

“This all had nothing to do with my job”

When doctors disclose a mental health problem to their employers, even voluntarily, the consequences can be traumatic and profound.

Justin Bullock, a medical resident, says UCSF Medical Center asked him to submit to a month-long fitness-for-duty assessment shortly after he was admitted to the same hospital for mental health treatment, following a suicide attempt in March 2020. Going into the process, Bullock was transparent about his mental health, including the diagnosis of bipolar disorder he had received in medical school. After the assessment, he says, he’s “so much less likely to ever want to get help, to ever be transparent about when I’m struggling.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22658641/VOX_Bullock_MD_pgannaway06_copy.jpg) Preston Gannaway for Vox

Preston Gannaway for VoxBullock says he underwent hair, blood, and urine testing for illicit drug use, a personality test, and a psychiatric evaluation involving probing questions about his childhood traumas, including sexual abuse. “I felt like this all had nothing to do with my job,” he says. “They never discussed or had questions about my performance at work in this evaluation.”

Indeed, Bullock had an outstanding clinical and academic record; he won numerous honors and awards during his residency, and got consistently glowing feedback about his performance with patients.

But if he’d had any serious mistakes on his record, he could have faced practice restrictions or even lost his medical license. Bullock says he has recovered from his suicide attempt, but not from the assessment. “There are a lot of parts of this process where they rip you of your humanity,” he says.

UCSF Medical Center did not comment on Bullock’s specific case, but wrote in a statement to Vox:

The mental health of our physicians is of tremendous importance as they face the ongoing stresses of their training and profession, compounded in the past year by the personal and professional challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is an issue that UCSF has taken very seriously for years and for which we continuously work to improve the support we provide.

USCF also called the program Bullock went through “entirely voluntary,” a characterization Bullock — who recently detailed the experience in an academic paper — disputes. “It is voluntary,” he says, “in that you can leave UCSF or let them put your license at risk by reporting you to the medical board.”

“There’s too much denial, too much shame”

The movement to improve mental health care for doctors is gaining momentum, thanks to campaigning physicians and grieving families like the Jolleys and Feists. Jackie Jolley is working with the University of Utah to try to give doctors the option of receiving treatment outside their own health systems. “We recognize it’s difficult for doctors to get help” in their own system, David Barnes, the president of Utah Emergency Physicians, told Vox. “We are looking for solutions.”

Last year, Breen’s family created the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation, and in July 2020, they got a bill introduced in the Senate with bipartisan support.

In March 2021, nearly a year after Breen’s death, the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee unanimously passed the legislation. If adopted by Congress, the law would immediately support suicide and burnout prevention training for all health care workers. It also provides research funding to study the causes of burnout in the profession, naming “stigma and concerns about licensing and credentialing” as key drivers to examine.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22660032/IMG_5919_20210417_182532.jpg) Courtesy of the Jolley family

Courtesy of the Jolley familyWe need better data not only about the drivers of the problem, but also about the precise number of doctors who die by suicide. Concerns about an elevated suicide rate in medicine have circulated since at least the 1920s, but we still don’t have definitive numbers.

“If it’s a problem anyone actually cares about, then there should be publicly available tracking and some effort to stop it,” one Boston-area doctor, who has lost two colleagues to suicide and spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of workplace retaliation, told Vox. “In what other industry would it be acceptable for talented and high-profile people to be jumping off buildings and everyone to stand by scared to comment?”

The University of Michigan’s Katherine Gold suggests one fix for the data problem: State medical boards should cross-reference their members’ deaths each year with the CDC data she uses, on violent deaths by occupation, to make sure all physician suicides are tracked and accounted for. “That has not happened to date,” she says.

Several states, including Michigan and Virginia (where Breen was treated before her death), have introduced “safe haven” laws that protect the mental health medical records of health care professionals and allow them to seek care without fearing any repercussions.

But “the biggest systemic fix is simply to remove the mental health questions,” Gold says, echoing other reformers. This would have to happen not just on state licensing applications but everywhere doctors face them, from hospital credentialing to insurance reimbursement forms.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22666156/IMG_2639.jpg) Courtesy of the Jolley family

Courtesy of the Jolley familyThat might help with an equally urgent task: ending the stigma about mental health problems, says Jolley’s friend Myles Greenberg, the former ER doctor. “Like every other medical problem, you catch it early and intervene early and have a much better chance of a positive outcome,” he says. “There’s too much denial, too much shame — this cultural bullshit in medicine that’s preventing people from getting the care they need.”

“The good that can come out of this is to repeatedly tell this story,” he continues. “Not just the Scotts and Lornas, but the other people who suffered from this. The powers that be need to start getting it through their heads that this is a problem.”

CREDITS

Editors: Eliza Barclay, Katherine Harmon Courage, Daniel A. Gross

Visuals editor: Kainaz Amaria

Copy editors: Elizabeth Crane, Tanya Pai, Tim Williams

Fact-checker: Becca Laurie

Engagement editor: Kaylah Jackson

Author: Julia Belluz

Read More