Why experts say we need clinical trials before using the drug to treat the coronavirus.

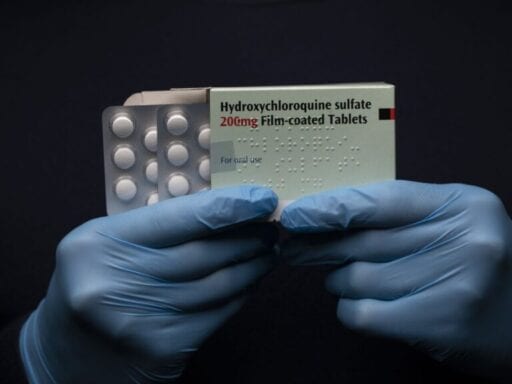

In the rush to treat the hundreds of thousands of people sick with the Covid-19 coronavirus, many — including President Trump — have touted the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine. This has led to shortages of the drug across the country.

But researchers know little about its effectiveness against the disease because rigorous scientific studies have not yet been conducted.

“The data are really just, at best, suggestive,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CBS’s Face the Nation on April 5. “There have been cases that show there may be an effect, and there are others to show there’s no effect. So I think, in terms of science, I don’t think we could definitively say it works.”

However, as Covid-19 spreads throughout the country, the need for an effective treatment is mounting. And as hospitals struggle with a lack of equipment and personnel, health workers are running out of options for how to help the infected.

That’s adding to the pressure to deploy a drug like hydroxychloroquine during the pandemic. Yet without robust clinical trials to verify its potential, the treatment could do more harm than the disease itself.

How we could find out if hydroxychloroquine is a good treatment for Covid-19

Clinical trials are the main way researchers figure out whether a drug works — and whether taking it is worth potentially harmful side effects. Doctors in individual cases can repurpose a drug like hydroxychloroquine that’s been cleared to treat other illnesses, prescribing it for off-label use.

But even drugs previously approved to treat one illness need clinical trials before they can be used as a widespread standard treatment for another condition. Repurposing drugs cleared for one purpose to use for another also has a tragic history of severe harm to patients.

Researchers also don’t know whether hydroxychloroquine is actually good at fighting against Covid-19. Most patients infected with the disease recover with no treatment. So scientists need to distinguish whether the drug is actually helping patients recover faster, or if they are getting better on their own, making sure that what they’re seeing isn’t due to chance.

The small sample studies and anecdotes around hydroxychloroquine that have emerged so far don’t cut it.

The gold standard for figuring out cause and effect is a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Here, patients are sorted randomly between those receiving the treatment and those in the control group, or those receiving a placebo. To make a study “double-blind,” not only do the patients not know if they are receiving the active treatment, the people administering it also don’t know (thus controlling for unintentional bias). These trials, when large enough, can yield robust results and overcome biases that emerge in smaller samples, like having a certain age demographic overrepresented in the study group.

There are now larger studies underway to resolve questions about the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine, some recruiting thousands of patients.

Such trials are especially important because of the scale of the Covid-19 pandemic. Millions of people are likely to contract the virus, and without widespread treatment, many of them will suffer and die. On the other hand, a treatment like hydroxychloroquine could do more damage than good if prescribed to patients without proper testing to see which circumstances make the most sense to use the drug.

But randomized controlled trials are expensive, and frustratingly time-consuming in the context of a mounting pandemic. It’s not surprising then that people are scrounging for whatever information is already available.

What we currently know about using hydroxychloroquine for Covid-19

The anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine, sold under the brand name Plaquenil, is also prescribed as an anti-inflammatory drug for conditions like arthritis and lupus. It’s a derivative of another anti-malaria drug, chloroquine.

Hydroxychloroquine is an appealing prospect because it’s already been tested in humans and is available in a low-cost generic form. Doctors in several countries, including the United States, France, China, and South Korea, have reported success in treating Covid-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine, sometimes paired with the antibiotic azithromycin.

But these are anecdotes that don’t offer much insight into how effective the drug could be in a wider population.

A laboratory study of hydroxychloroquine showed that it could prevent SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind Covid-19, from entering cells in a petri dish. While it shows a plausible mechanism for the drug, the effects on cells in a dish can be different than in living people.

Human trials of hydroxychloroquine, by contrast, have so far yielded mixed results. A tiny study by researchers in France found that the drug could clear the infection in a few days. But the study sample included only 36 patients, and the trial wasn’t randomized, meaning the administrators were deliberately picking which patients received the treatment, potentially skewing the results.

Other studies have been even less promising. A study in China found that hydroxychloroquine was no better than standard medical treatments without the drug. This study was also small, 30 patients, but the treatment was randomized. Another study in France among 11 patients found that hydroxychloroquine was ineffective at best, with one patient dying, two transferred to an intensive care unit, and one patient who experienced a dangerous heart problem and had the hydroxychloroquine treatment stopped early.

In Sweden, some hospitals have stopped offering the drug after some patients reported seizures and blurred vision.

The listed side effects of hydroxychloroquine are long and well-known. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has reported problems like irreversible retinal damage, cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness, and a severe drop in blood sugar. There are psychiatric effects as well, including insomnia, nightmares, hallucinations, and suicidal ideation. The drug can also have harmful interactions with medicines used to treat diabetes, epilepsy, and heart problems.

These side effects are a big reason why the World Health Organization no longer recommends hydroxychloroquine as the routine treatment for malaria.

High blood pressure and diabetes, for example, already make the infected more likely to suffer severely from Covid-19. So a treatment like hydroxychloroquine could worsen those underlying conditions, or could result in a dangerous interaction with the medicines used to treat those conditions.

Some health workers have been hoarding hydroxychloroquine as a means to ward off the illness. Several patients who need the drug for approved uses have reported trouble getting their prescriptions filled. But there’s no evidence that the drug works as a prophylactic for Covid-19.

Some of the rules for drugs like hydroxychloroquine have now been relaxed to allow doctors to experiment with treatments for patients in dire need during the pandemic.

The FDA has granted emergency use authorization of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine to fight Covid-19. But expanding the use of these drugs to sick but not critical patients still warrants further testing due to the potential side effects.

More than 50 clinical trials for the drug are now planned or underway around the world. But while randomized controlled trials do help health workers figure out how to safely deploy drugs, they don’t guarantee the drug will work for everyone, nor will they eliminate risks completely.

Author: Umair Irfan

Read More