A group of Senate Republicans is countering Joe Biden’s Covid-19 relief proposal.

Two weeks after President Joe Biden released his opening bid on an economic stimulus plan, Senate Republicans are out with theirs. And there is quite a bit of distance between them.

In an outline unveiled Monday, 10 Republican lawmakers laid out their $618 billion proposal for a relief package, which includes less than a third of the funds in the $1.9 trillion rescue plan Biden has introduced.

The offer shows a fundamental difference in how Republican lawmakers want to approach the public health and economic crises: Namely, they want something more targeted and aren’t interested in a comprehensive approach. Biden — and many economists — have said that the country does in fact need more expansive support to endure the fallout from Covid-19. Democrats are also wary of going too small on stimulus and repeating the mistakes of the 2009 Great Recession, when Congress was too conservative in its response, resulting in a slower and more uneven recovery.

Republicans, however, have said they prefer a narrow plan that tackles more immediate public health needs like distributing the vaccine. And they want to make sure the funding from Congress’s most recent stimulus package — approved in December — is fully spent first.

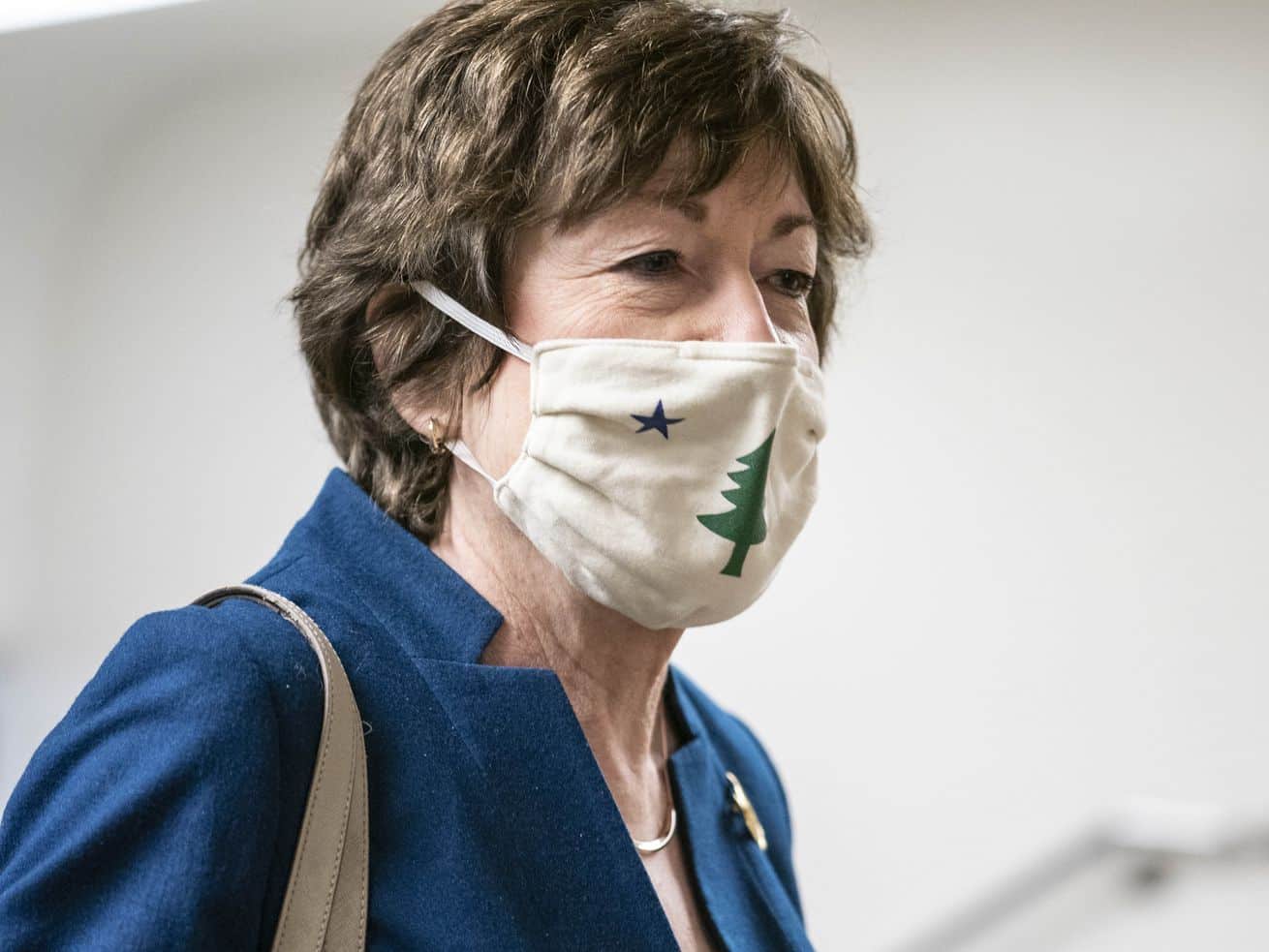

“While I support prompt additional funding for vaccine production, distribution, and vaccinators, and for testing, it seems premature to be considering a package of this size and scope,” Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME), a leader on the Republican plan, previously said in a statement. She introduced the proposal alongside nine colleagues, Sens. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), Bill Cassidy (R-LA), Mitt Romney (R-UT), Rob Portman (R-OH), Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV), Todd Young (R-IN), Jerry Moran (R-KS), Mike Rounds (R-SD), and Thom Tillis (R-NC).

Republicans’ plan includes not only substantially less funding for provisions like school reopening, it completely leaves out support for state and local governments, and reduces the amounts allocated to direct payments (aka “stimulus checks”) and weekly enhanced unemployment insurance.

The area where it’s most consistent with Biden’s is in the $160 billion in funds that it allocates for testing, vaccines, and personal protective equipment for medical professionals. As experts have emphasized, state and local funding is critical to save public and private sector jobs, while direct aid is central to helping people cope with job losses that have resulted during the pandemic.

Republicans’ proposal doesn’t go far enough in addressing the scope of the current crisis, economists told Vox. Additionally, it casts doubt on whether there’s real interest on the Republican side for a bipartisan relief package, given how far apart Republicans and Biden are on their plans.

“I think it’s bad economics, and I think it’s really bad politics,” said Stony Brook University economics professor Stephanie Kelton, of the GOP plan. “It’s too shortsighted, and it’s not taking on the threat.”

If Biden is unable to pick up Republican support for this bill, Democrats have the ability to approve parts of the legislation unilaterally via a process known as budget reconciliation. While most bills require 60 votes to pass, a budget measure would only need 51. Democrats’ ability to use this process also depends on whether their caucus stays united on the bill, which is not certain yet, either.

What’s in the Republican proposal

The GOP measure overlaps with Biden’s in a few areas, including money for the public health response and funding for food aid, while differing significantly on other provisions including unemployment insurance and direct payments. Other provisions aren’t included in the GOP proposal at all, but more on those later. Here’s what’s similar — and different — between the two plans.

What’s similar to the Biden plan

- $160 billion for vaccines and testing: Like Biden’s plan, the Republican one includes $160 billion in funds to boost the public health response. That total has $20 billion dedicated to establishing a national vaccination program in partnership with states, tribes and territories; as well as $50 billion to expand testing. It also contains $10 billion for more personal protective equipment along with other pandemic supplies, and $30 billion for the Disaster Relief Fund. There’s $35 billion allocated for a relief fund aimed at hospitals and other medical service providers with a fifth of that money set aside to help rural hospitals that have dealt with revenue shortfalls as well as cost surges. Funding for vaccines and testing is among the areas where Biden and Republicans have the most common ground, and the two bills include identical amounts for this effort.

- $12 billion for food aid: Republicans, like Biden, would extend a SNAP enhancement until the end of September, and allocate $3 billion to WIC, a supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and children.

- $4 billion for behavioral health: There’s $4 billion set aside for mental health and substance abuse services in the GOP bill that’s similar to what Biden has included as well.

What’s different from Biden’s plan

- The GOP plan offers a shorter extension of enhanced UI, and less weekly support: Republicans have some money for unemployment insurance, though they support a smaller weekly enhancement and would extend supplemental funding for less time than Democrats would. Republicans’ plan would maintain $300 in weekly enhanced UI through June 30, while Biden’s proposal would provide $400 in weekly enhanced UI through September. A current weekly UI enhancement is set to expire on March 14, so Congress must pass an extension of the program to ensure that people are able to keep receiving these benefits.

- There’s half the funding allocated for child care: The GOP proposal contains half as much funding for childcare as Biden’s, with $20 billion dedicated to the Child Care and Development Block Grant program. Biden’s, meanwhile, had $15 billion allocated to this same program, and an additional $25 billion for an emergency stabilization fund for childcare providers.

- There’s also significantly less money for school reopening: There’s much less in the Republican plan for school reopenings: $20 billion versus the $130 billion allocated in Biden’s proposal.

- The two plans approach small business aid differently: The GOP plan adds more funds to loan and grant programs intended to help small businesses weather the pandemic including $40 billion for the Paycheck Protection Program and $10 billion for Economic Injury Disaster Loans. Biden’s proposal would use a similar amount of money, but in a different way, providing $15 billion in grants for small businesses and using $35 billion in federal funding to help finance small businesses.

- The GOP proposal offers reduced stimulus checks and increases limits on who gets them: Republicans also back another round of stimulus checks, though they would be $1,000, compared to the $1,400 that Biden proposed. Republicans are also moving to limit stimulus checks to individuals that make $50,000 or less, and couples that make $100,000 or less. These payments would include $500 for dependent adults and children.

What’s not in the proposal

The Republican proposal leaves whole issue areas out completely including state and local government aid, paid sick leave and an increase to a $15 minimum wage. Below are a few issues it does not address that are covered in the Biden proposal.

- State and local aid: The Biden plan has $350 billion allocated to help states and local governments meet budget shortfalls, and cover costs for everything from teacher salaries to public transportation systems. Republicans’ plan, however, does not address this issue whatsoever — an approach that could put states in a treacherous financial position moving forward.

Most states have balanced budget requirements, which mean they can’t really spend more than they take in. And during the Covid-19 pandemic, many states have seen a decline in tax revenue and an increase in spending to respond to the outbreak. Some Republicans have tried to cast help for states now as a “blue state bailout,” but Democratic-leaning states aren’t the only ones affected. As the New York Times pointed out in December, some states have done better than expected in the crisis, and it doesn’t really line up with who they voted for in the 2020 election. California and Wisconsin, for example, have been able to regain lost tax revenue. Texas and Florida have not.

When states cut spending, that means they cut jobs and services, and it’s a drag on the economy. “Whether it’s tax increases or spending cuts, states tend to take money out of the economy during periods of stress, and that is not only financially difficult for their residents, but it also tends to delay the economic recovery,” Josh Goodman, a state economic development officer at Pew Charitable Trusts, told Vox last year.

In the wake of the last financial crisis, Pew Charitable Trusts estimates that states missed out on $283 billion in the decade following 2008 in tax dollars.

- Paid sick leave: A paid sick leave program established in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act last year guaranteed ten days of paid sick leave for people who were sick or quarantining because of Covid-19. That program has since expired and Biden’s plan would extend it through the end of September.

Researchers have found that states which implemented the prior paid sick leave program had 400 fewer Covid-19 cases reported per day. Republicans’ plan, however, omits this provision, which is one that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell fought to keep out of the previous stimulus bill.

Biden’s plan would also eliminate prior exemptions, which meant that companies with less than 50 employees, or more than 500 employees, were not required to provide paid sick leave. The full costs of the paid sick leave for businesses with less than 500 employees would be covered by a tax credit.

- A $15 minimum wage: Biden’s proposal called for raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. It’s an important Democratic priority, though it’s not necessarily a Covid-related one. This is one of the proposals Republicans are least likely to get onboard with — and one it’s not clear Democrats can do on their own. If Democrats wind up passing stimulus through budget reconciliation, it’s not clear if a $15 minimum wage will fit under those rules.

- Expansion to the child tax credit: Like the minimum wage, an expanded child tax credit is another issue Democrats are pushing for. Biden’s plan would expand the tax credit to $3,000 per child up to age 17 and $3,600 for children under age 6 for one year. Biden’s team argues that this, combined with other elements of his plan, would have an enormous impact and would cut child poverty in the US in half.

Democrats are angling to go bigger, and many economists agree

There isn’t a strict line among economists about exactly how much support is needed, but the growing consensus is that Congress risks doing too little, not too much, on economic stimulus.

“To put it simply, we need that bridge to get us to a post-Covid world,” said Greg Daco, chief US economist at Oxford Economics. “The big thing is that we don’t know how long or how strong of a bridge we need, because we don’t know when we’ll get there.”

In 2009, Democrats passed the $800 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act believing that they’d likely have another shot at doing another bill later. They didn’t, and many economists believe that made the recovery worse.

“When Democrats passed the recovery act in 2009, it was smaller than was necessary, and a lot of members thought there was going to be another bite at the apple. There wasn’t,” one Democratic aide recently told Vox. “Members who were around in that time period are very much cognizant of that lesson.”

While Biden’s team has said they want to talk to Republicans about their proposal, they have been clear they want to do more, simultaneously. “One thing we’ve learned over the past 11 months is a piecemeal approach, where we try to tackle one element of this and wait and see on the rest, is not a recipe for success,” said Brian Deese, the director of the White House’s National Economic Council, in a Meet the Press interview on Sunday.

It’s a matter not just of how many dollars are needed, but also how quickly they get out the door. Some programs under the current stimulus are set to expire soon — expanded unemployment insurance, for example, dries up in mid-March. If Congress does strike a deal to extend benefits, if it procrastinates too much, there will be likely be hiccups in the interim as programs reset.

Right now, no one knows what exactly the right amount is, or when the pandemic will end. “We’ll only know when the crisis is over in a few years, when we look back and say this was helpful or not,” Daco said.

Progressives are pushing the Biden administration to go bigger on the stimulus, not smaller. Or at the very least, that his opening $1.9 trillion doesn’t shrink. “‘We’re going to be monitoring very closely to make sure the $1.9 trillion package doesn’t get whittled down, and I would argue that if something gets stricken…then something else should get beefed up,” said Lindsay Owens, interim executive director of the progressive policy group the Groundwork Collaborative.

Last year, before the passage of a $900 billion stimulus package, the Groundwork Collaborative released an estimate that Congress needs to inject $3 to $4.5 trillion into the economy to get it to reach its full potential. “More is more, and we can definitely add to [Biden’s proposed] package,” she said. “We shouldn’t be horse trading in a way that diminishes the impact of the relief.

To be sure, not all economists are on board that the swing needs to be that big. Marc Goldwein, senior policy director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a bipartisan group that advocates for fiscal responsibility, said that he believes the right amount for the next Covid-19 relief package is likely somewhere between the Senate GOP’s proposal and Biden.

He noted that the Congressional Budget Office just updated its new economic output gap estimates — basically, the difference between how much the economic will grow compared to how much they think it could grow — and that they basically think the economy will fall about $400 billion short this year and $800 billion short through 2025. “I think it’s worth negotiating with,” he said of the Republican package. “The Biden package gets a lot of the right elements, but there’s plenty of room to pare it back.”

Even though Goldwein and his group aren’t aligned with the go-big economist crowd, they do agree that more needs to be done on aid for states and localities. “This is the area that we’ve fallen short,” he said.

Democrats could move ahead with Biden’s plan this week

Senate Republicans are meeting with Biden on Monday evening in an attempt to figure out if a bipartisan relief package is possible. Biden has emphasized that he wants to try for a bipartisan approach on this bill, though Democrats could well move forward without Republican support if lawmakers remain dug in on their respective positions.

The $1.9 trillion Biden bill seems unlikely to garner even one Republican vote, let alone the ten it would need to hit the 60-vote threshold, raising questions about whether there will be a compromise option, or if the White House will ultimately support advancing legislation with just Democratic support.

“I don’t think there’s a single Republican who would vote for the $1.9 trillion bill,” Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) told Politico last month.

This dynamic suggests that — unless Republicans and Biden can find some type of middle ground that assuages both of their concerns — Democrats may be forced to advance Covid-19 relief via budget reconciliation.

“The work must move forward, preferably with our Republican colleagues, but without them, if we must,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer previously said in a floor speech.

Republicans are hoping that Biden’s previous focus on bipartisanship and expressed interest in working together could potentially lead to a different result.

One thing to keep in mind as the debate over stimulus moves forward: The big bipartisan bills Congress passed in 2020 at the onset of the pandemic really made a difference in the economy and in people’s lives. The situation would likely have been much more dire, with more people slipping into poverty, household savings dissipating, businesses shuttering at a higher rate had Washington not stepped in.

“We know from the past nine months that if you get money into the right hands, if you limit the economic damage as much as possible, then you’ll emerge stronger,” Daco said. “So in that context, why not have spending help plug the holes?”

Author: Li Zhou

Read More