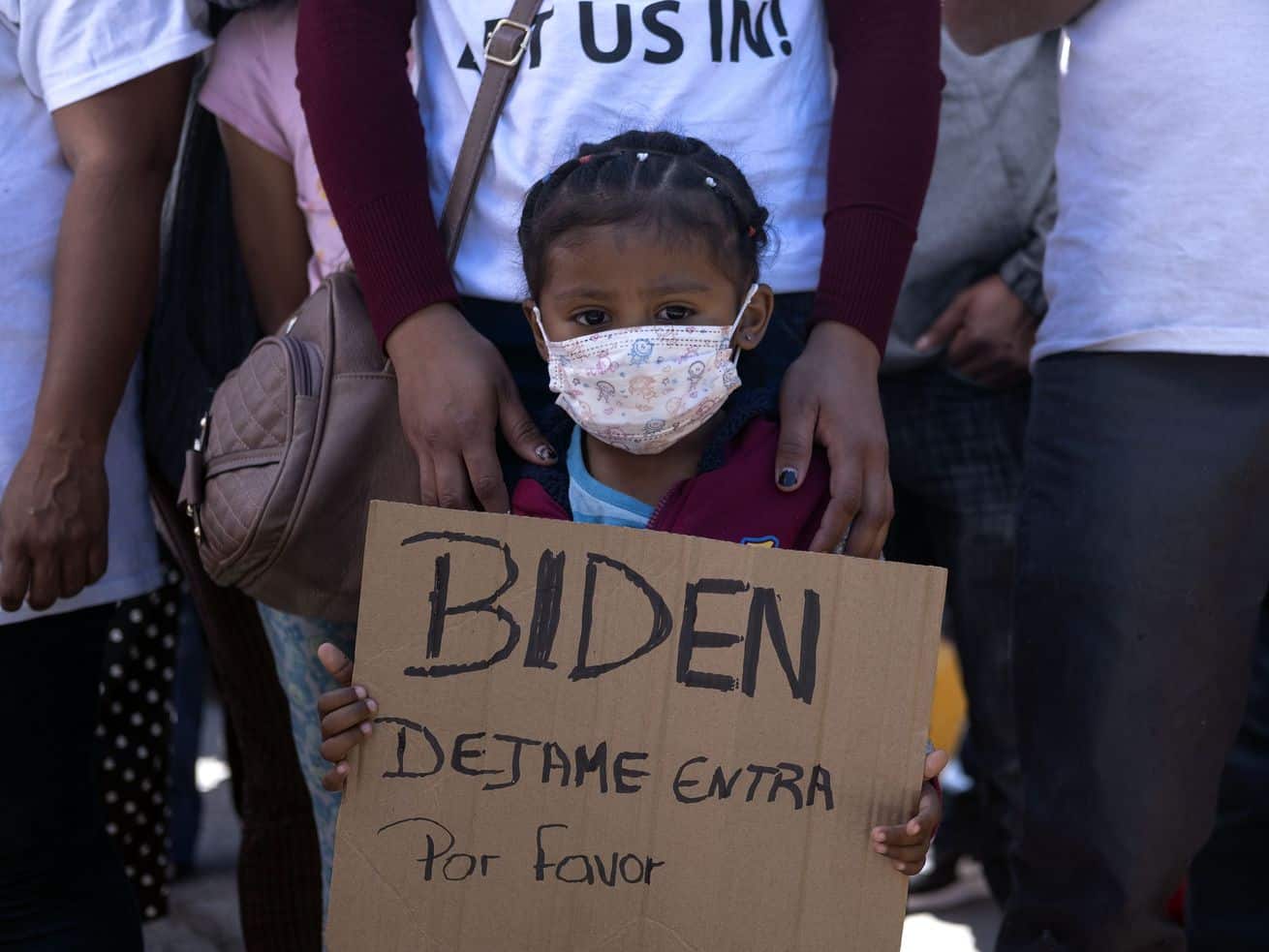

Biden is seeking an “effective and humane” border policy. He’s struggling to deliver.

As unaccompanied children from Central America arrive in increasing numbers on the US-Mexico border, the Biden administration has been caught unprepared and under-resourced, struggling to fulfill its commitment to treating migrants humanely as the number of children held in US Customs and Border Patrol custody hits a record high.

Administration officials have urged patience as they review the dysfunctional system under which migrants are currently processed at the border and seek to dismantle former President Donald Trump’s complex web of policies that put asylum and other humanitarian protections out of reach for most people. For now, that means that the vast majority of migrants are still being turned away.

But though the White House has has declined so far to call it a “crisis,” the situation is increasingly dire: As of Wednesday, more than 3,700 children were reportedly being detained in US Customs and Border Protection temporary holding facilities designed for adults for longer than they are legally permitted — a record high. These are the same facilities that generated widespread outrage under the Trump administration where children slept with nothing but mylar blankets to keep them warm at night on concrete floors.

Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said Saturday that a CBP facility is “no place for a child,” but that border agents are “working around the clock in difficult circumstances to take care of children temporarily in our care.”

CBP officials are struggling to quickly transfer them to state-licensed shelters for migrant children, which have had to drastically slash their capacity amid the pandemic and where beds are now full. That has forced the administration to reopen temporary tent facilities in Carrizo Springs, Texas, which are costly and not subject to the same level of oversight as permanent shelters.

On Saturday, the administration also announced that the Federal Emergency Management Agency would help “receive, shelter and transfer” unaccompanied children over the next 90 days. The agency is now working to expand the capacity of shelters designed to administer care to children.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the same crisis has been playing out cyclically since at least 2014, when the US saw a dramatic shift in the kinds of migrants who were arriving at the southern border from primarily single-adult Mexicans to families and children from Central America’s “Northern Triangle”: Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

In the years since, the federal government has failed to adapt to ensure that children and families are treated humanely. That burden is now on Biden.

“This isn’t a new flow that we’re just seeing because Biden is coming into office,” Jessica Bolter, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, said. “The US government still hasn’t figured out exactly how to manage this flow of families and children. And throughout the Trump administration, the government neglected to find a way to adjust US border enforcement mechanisms in a way that protects their rights, but also exerts control over the system.”

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Wednesday that the administration is continuing to prioritize “humanity” in processing unaccompanied children, but is still “working on putting in place policies that can address what we’re seeing.”

The Biden administration is struggling to accommodate rising numbers of unaccompanied children

While most migrants are still being turned away at the border, the Biden administration began accepting unaccompanied children in February in a reversal of Trump-era policy. Most of them have been stranded in Mexico for a year under that policy despite their right to seek protection under federal law and are now seeking to reunify with family in the US.

Since 2014, the number of unaccompanied children arriving at the southern border has remained above 40,000 annually, peaking at more than 72,000 in 2019 under Trump.

Though CBP has publicly refused to share the number of unaccompanied children currently in its custody, claiming that it is “law enforcement sensitive,” CNN reported that over the last three weeks, the agency had encountered an average of 435 children daily — an increase from the previous average of about 340 children. They are spending an average of 107 hours in CBP custody, exceeding the 72-hour legal limit before they are supposed to be transferred to Department of Health and Human Services shelters, according to the Washington Post.

At least 8,500 children are currently in those shelters are awaiting release to sponsors, who are typically family members, but can also include foster families. That includes the temporary influx facility in Carrizo Springs, which, unlike a permanent shelter, is not licensed by the state, raising concerns that the up to 700 teenagers that can be housed in the facility could be subject to inhumane treatment and prolonged confinement.

“KIND will be monitoring the treatment of these children to ensure that they are not held in these facilities longer than absolutely necessary,” said Megan McKenna, a spokesperson for the legal aid group Kid in Need of Defense, which has long represented unaccompanied children. “Key will be finding ways to release the children to vetted sponsors as quickly as possible without taking any shortcuts that would undermine their safety.”

One potential solution is co-locating US Department of Health and Human Services staff in CBP facilities to facilitate screening of migrant children and swift release to sponsors. Some of this coordination and information sharing can be done from Mexico, before the child enters the United States, McKenna said.

The administration also announced Wednesday that, in an effort to reduce the pressure on resources at the border, it is restarting the Central American Minors program, which allows children in danger to apply to come to the US from their home countries instead of having to come to the US-Mexico border to do so. Trump had ended the program after taking office, leaving around 3,000 children stranded who had already been approved for travel.

KIND has called on the administration to expand eligibility for the program beyond children with parents in the US who have legal status, McKenna said.

Psaki said Wednesday that the administration is also looking to increase the number of available HHS shelters and “safely” expand bed space in existing facilities while complying with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.

On Friday, the administration took another step to more swiftly release children in custody to sponsors. The Department of Homeland Security announced that it was terminating a 2018 agreement with HHS under which sponsors were subject to more stringent vetting, which involved getting their fingerprints taken and additional paperwork. That information was shared with child welfare and immigration authorities, leaving the sponsors potentially vulnerable to deportation if they did not have legal status.

The Biden administration has signed a new memorandum in its place, but it’s not immediately clear what that entails.

Biden is still turning away the vast majority of migrants

Biden has kept in place a Trump-era policy that has allowed the US to expel nearly all migrants arriving on the southern border with no due process on the grounds of curbing the spread of Covid-19.

The Trump administration began expelling migrants to Mexico in March under Title 42, a section of the Public Health Safety Act, that allows the US government to temporarily block noncitizens from entering the US “when doing so is required in the interest of public health.” At least 13,000 such children were expelled under the policy, often with little if any notice to their parents or legal counsel and even if they show no symptoms of the virus. Others were held in hotels along the border for extended periods of time under the program.

Since he took office, Biden has created narrow exceptions to the policy for unaccompanied children and asylum seekers who were sent back to Mexico to await their day in court in the US under the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols. Last month, Mexico also stopped accepting some families with children under the age of 12 due to a change in its laws concerning the detention of children, so they have been released into the US instead.

But the vast majority of migrants still can’t enter the US under the policy. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has recently argued that the US is “obligated, in service of public health” to keep the restrictions in place.

But it’s not clear that there is a public health rationale for keeping the policy in place, given that the level of community transmission inside the US is already so high. Immigrant advocates have argued that the US can safely continue to give protection to vulnerable immigrants.

Trump’s restrictive border policies created pent-up demand

US immigration authorities reported more 100,000 migrant encounters over the course of four weeks ending on March 3 — the most recorded over the same period in five years. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the US is currently witnessing a “surge” in new migration.

That number includes thousands of single adults who, after being turned away at the border under the pandemic-related Title 42 restrictions, are often caught trying to cross again. Before the pandemic, they might have been dissuaded from trying again for fear of facing criminal prosecution for illegal entry and disqualifying themselves from legal migration pathways, such as asylum. But under the Title 42 process, they are merely fingerprinted, processed and dropped off in Mexico without consequence.

Erika Pinheiro — the Tijuana-based litigation and policy director for Al Otro Lado, a nonprofit that provides legal aid to migrants — said that many of the migrants her organization encounters have been waiting in Mexico for a chance to cross the border for a year or more. The border has effectively been closed since last March, but before that, Trump had put in place a complex network of policies designed that made it next to impossible for migrants to apply for asylum or other protections.

Over 9,000 asylum seekers were on a waiting list to be processed at ports of entry as of last March, before the Title 42 restrictions went into effect.

More than 71,000 asylum seekers were also stranded in Mexico under Trump’s Migrant Protection Protocols over the lifetime of the program. While the Biden administration has sought to end the program and started processing the 28,000 people with active cases, many people whose cases were closed are also still waiting in Mexico in the hope that they will eventually be processed. (Biden administration officials have signaled that they eventually intend to identify those people and admit them to the US for a chance to seek protection.)

Pinheiro said that, compared to those who have waiting in Mexico long-term, the number of new arrivals is relatively low. (NBC reported that they accounted for less than 10% of migrants in Tijuana, which is across the border from San Diego, California.) But their presence has become more noticeable after some 1,500 set up a camp in Tijuana. Under normal circumstances, CBP could process them and empty out the camp within two weeks, but that’s not happening.

“This isn’t a ‘surge,’” Pinhiero said. “I think the problem is that processing is completely closed so the migrants who are arriving are very visible.”

The Biden administration has told migrants not to come — but many of them are desperate

For now, the Biden administration’s message to migrants is, “The border is not open” and “Do not come in an irregular fashion.” But there is hope among migrant communities in Mexico that the new administration will eventually offer them protection given that Biden has sought to pursue more immigrant-friendly policies than his predecessor.

“There was a significant hope for a more humane policy after four years of pent-up demand,” Roberta Jacobson, the former ambassador to Mexico and chief White House coordinator for the southern border, said during a press conference on Wednesday.

Smugglers have also been spreading misinformation about the Biden administration’s plans to process asylum seekers in an effort to profit from it. Pinheiro said she has heard rumors spreading that migrants staying in certain camps will be processed or that the borders would open at midnight.

But that’s not to say that favorable policies from the Biden administration are primarily what’s driving people to migrate. Pandemic-related economic deterioration and hurricanes that devastated Central America late last year, as well as more longstanding issues such as gang violence, government corruption and crop failures due to climate change in the region are among the factors pushing people out of their home countries to make the perilous journey north.

“If people are already struggling with crop failures or their house has been destroyed by a hurricane or they’re being extorted, and then they hear that there’s a new administration coming in that’s going to treat migrants better, that could be kind of the tipping point where they say, ‘Now is the right time to migrate.’ But it wouldn’t come out of the blue,” Bolter said.

Author: Nicole Narea

Read More