The leaks that plagued the DNC, John Podesta, and others are crucial to the collusion probe. Were any Trump associates involved?

There’s one positively enormous shoe that still hasn’t dropped in special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference with the 2016 campaign: an indictment about all those hacked emails.

The hacking and release of leading political figures’ emails is the most visible election intervention attributed to Russia’s government. And it’s long been one of the leading, and perhaps the leading, possibility about just what “collusion” between Donald Trump’s team and the Russians might have involved.

That’s not mere speculation. We’ve gradually learned of not one but six times Trump associates at least tried to get involved with either Russian-provided dirt, hacked Democratic emails, or WikiLeaks. We don’t yet know whether these furtive contacts resulted in anything of significance — but one of these advisers, George Papadopoulos, has already pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about the matter and has begun cooperating with Mueller’s team.

These hacks were crimes, victimizing many hundreds of Americans (those who had their documents stolen, and those who corresponded with them). The operation was more wide-ranging than many remember, targeting not just John Podesta and the DNC but many other people and groups. It wasn’t just emails stolen, either — posted material ranged from Democratic Party turnout data that a Republican operative thought was “probably worth millions of dollars” to even a purported picture of Michelle Obama’s passport.

No charges have been filed in the matter — yet. But some are likely coming. The Wall Street Journal has reported that the US has identified “more than six members of the Russian government” involved in the DNC hacks. And the Daily Beast wrote that investigators have identified a specific Russian intelligence officer behind “Guccifer 2.0,” a leading figure in the hacks. Mueller is now overseeing the probe.

To understand what happened in 2016, we have to understand the hackings. And though some mysteries remain, much of the complex story has gradually been pieced together by journalists and cybersecurity experts. The consequences, of course, unfolded in plain sight during the campaign itself.

How the hacks happened (a phishing expedition)

The media often shorthands the 2016 hack story as: Russians hacked Podesta and the DNC’s email accounts, and WikiLeaks then posted those hacked emails publicly.

The full story is more complex. Let’s start at the beginning.

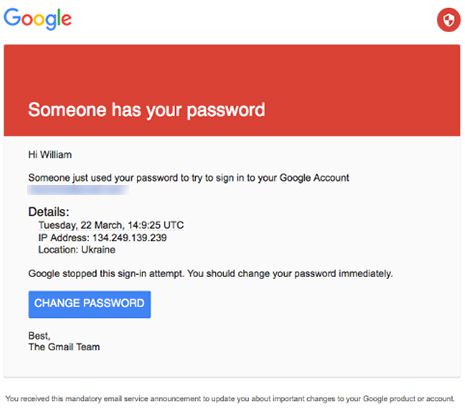

Between March 2015 and May 2016, a group of hackers went on a phishing expedition. The “baited lines” they cast out were at least 19,000 malicious emails that resembled the one below:

The Smoking Gun

The Smoking GunThese emails were designed to look as if they were coming from Google. But they were in fact designed to trick people into clicking through and entering their login credentials — delivering them right into the hackers’ hands.

According to a later Associated Press analysis of a report by the information security firm SecureWorks, at least 573 of the more than 4,700 email addresses targeted were American. They included many US government officials, military officials, intelligence officials, and defense contractors.

Particularly beginning in March and April 2016, these targets began to include many Democrats as well. Per the AP, more than 130 Democratic accounts were sent these malicious links, compared to just “a handful” of Republican accounts. Podesta and several Clinton staffers — along with former Secretary of State Colin Powell, retired Gen. Philip Breedlove, and others — had their accounts successfully compromised. (We know all this because the hackers used the link-shortening tool Bitly to do their work and accidentally left their activity publicly viewable.)

Russia was eventually blamed for the phishing expedition, for several reasons. For one, SecureWorks concluded the particular malware used in this campaign was tied to a hacking group that outside researchers had been tracking for some time — a group they thought to be linked the GRU, Russia’s foreign military intelligence agency. We don’t know what the secretive hacking group calls itself, but various cybersecurity researchers had given it several names: Iron Twilight, APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) 28, Pawn Storm, and — most famously — “Fancy Bear.”

Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Sean Gallup/Getty ImagesCircumstantial evidence also suggests a Russian-tied culprit. For instance, the phishers were extremely focused on Ukraine — at least 545 targeted email accounts were from there, comparable to the number of American targets. These included Ukraine’s president and many other top government officials, who are hostile to Vladimir Putin’s regime.

The Russians targeted, meanwhile, were generally critics of Putin’s government and journalists. Another interesting detail, per the AP, is that more than 95 percent of the malicious links were created between the hours of 9 am and 6 pm, Monday to Friday — Moscow time.

Around April 2016, as this phishing campaign increasingly began to target Democrats, material was also taken from the DNC. The firm Crowdstrike attributed this as a hack from Fancy Bear, citing the malware used, and other firms agreed with this assessment. These firms also concluded that a separate group of Russian-tied hackers (dubbed “Cozy Bear”) had been in the DNC’s systems for much longer, since all the way back in the summer of 2015.

The precise mechanisms of how the DNC was breached remain somewhat murky. But Fancy Bear’s phishing campaign did send out malicious links to nine DNC email accounts in March and April 2016. And as we’ll soon see, hacked DNC material ended up in the same place as hacked material from Podesta and others. A January 2017 US intelligence report would later specifically blame Russia’s GRU — the agency thought to be behind Fancy Bear — for taking “large volumes of data from the DNC.”

As striking as all this may seem, though, government-backed hacking is far from unusual. The US does it. Our allies do it. Our rivals do it. China was said to have hacked Barack Obama and John McCain’s presidential campaigns in 2008 and was then tied to a massive theft of federal data in 2015. Foreign intelligence agencies trying to peek into political activities seemed to be something that just, well, happened all the time.

What came next in 2016, however, was a jarring departure from these norms — the hacked information began to be posted publicly, in massive amounts.

A timeline of odd events between the hacks and the leaks

The backdrop to all of this was the US presidential election — the first series of primaries and caucuses took place in February and early March. The surprisingly Russia-friendly Donald Trump emerged as the clear leader in the Republican contest, over his Putin-critical rivals Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio. Meanwhile, Hillary Clinton, with whom Putin’s regime had long had chilly relations, emerged as the favorite for the Democratic nomination over Bernie Sanders.

It was around this point — in mid-March 2016 — that the phishing campaign began to particularly target many Democrats’ and Clinton campaign staffers’ email accounts, according to SecureWorks’ analysis.

There were several other events that, in retrospect, are either relevant or at the very least intriguing:

Mikhail Klimentyev/TASS

Mikhail Klimentyev/TASS- April 7: Putin condemns the Panama Papers leak. In early April, an international consortium of journalists published reports on a cache of leaked documents tracing offshore wealth — the Panama Papers. Many of the documents revealed financial information about Putin’s inner circle, and Putin publicly claimed the stories were part of a US plot against Russia. “They are trying to destabilize us from within in order to make us more compliant,” he said. Many have posited that the Russian government may have then wished to retaliate.

- April 19: The domain for DCLeaks, a website that would eventually post many hacked documents, is registered. For now, nothing is posted. (US intelligence agencies have said Russia’s GRU is behind the site.)

- April 26: George Papadopoulos gets an intriguing tip. Papadopoulos, a young foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign, sat down in London with a professor named Joseph Mifsud. Mifsud told him he’d just traveled to Moscow and met high-level Russian government officials. He added to Papadopoulos that Russia had obtained “dirt” on Hillary Clinton, in the form of thousands of emails.

- June 6 to 8: DCLeaks begins posting, but not about the election. DCLeaks’ posts of hacked documents indicated that it was Russian ties. That’s because they included the hacked emails of retired Gen. Philip Breedlove, who had commanded NATO forces in Europe and pushed for a harder line against Russia in Ukraine. They also included documents from George Soros’s Open Society Foundation. (The Russian government has blamed Soros and his associated groups for opposing its interests in Ukraine.)

- June 9: The Trump Tower meeting: Shortly afterward, Donald Trump Jr., Paul Manafort, and Jared Kushner met a Russian lawyer and four other people with Russian ties at Trump Tower. Don Jr. had agreed to take the meeting based on the promise of “official documents and information that would incriminate Hillary,” as part of “Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump” (as it was put to him in an email). Everyone involved claims nothing came of this meeting.

Throughout all this time, there was no public indication that the phishing campaign, or the hacking of the DNC and other campaign figures’ emails, had taken place. Just days later, that would change.

The email leaks begin

Jack Taylor/Getty Images

Jack Taylor/Getty ImagesOn June 12, 2016, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange dropped a bombshell. “We have upcoming leaks in relation to Hillary Clinton,” he announced, during a British television interview. “We have emails pending publication.”

WikiLeaks — a nonprofit launched back in 2006 by Assange, an Australian activist — had previously been most famous for posting a plethora of internal US military documents about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars (including video of a deadly airstrike) and more than 250,000 diplomatic cables from the US State Department — leaked by Chelsea Manning. Assange was then accused of rape and sexual assault in Sweden, and he sought political asylum from Ecuador. He has been holed up in the nation’s London embassy since June 2012.

Assange’s announcement was the first public indication that Democrats would soon be plagued by leaked internal emails. So two days after that, the DNC, which had learned of the hacking of its systems and hired Crowdstrike to respond, decided to get in front of what it feared was coming. The committee told the Washington Post that it had been hacked — by, it claimed, the Russian government. Crowdstrike’s CEO put up a blog post explaining why he identified Russia as the culprit.

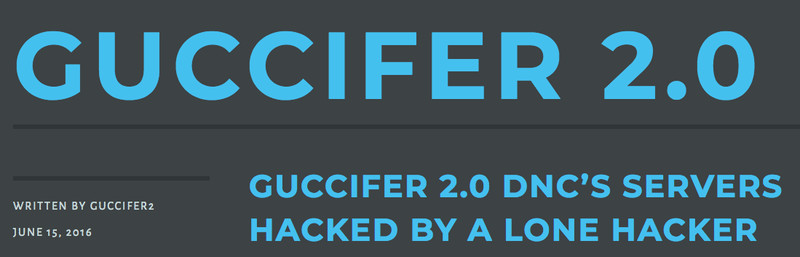

Yet the next day, June 15, things got even weirder — because that is when “Guccifer 2.0” arrived on the scene. (The name, a portmanteau of “Gucci” and “Lucifer,” is an homage to the original Guccifer, the jailed Romanian hacker Marcel Leher Lazar, who’d broken into high-profile Americans’ email accounts.)

In a WordPress post, the new Guccifer said that Crowdstrike was quite wrong about the DNC hack, which he said was carried out by him, “a lone hacker.” (“Fuck CrowdStrike!!!” he wrote.) He said that he’d given “the main part of the papers, thousands of files and mails” that he’d stolen, to WikiLeaks. (WikiLeaks has refused to confirm that he was its source.) He also began to post several documents he claimed were from the DNC server.

Image from from Guccifer 2.0’s WordPress

Image from from Guccifer 2.0’s WordPressAlmost immediately, journalists pointed to inconsistencies in Guccifer’s story and linguistic tics to suggest he was Russian — or more than one Russian. (US intelligence agencies would eventually say Russia’s GRU was behind the persona, and the Daily Beast recently reported that the account’s user once slipped up and neglected to mask his identity through a VPN — allowing investigators to match a particular Russian intelligence officer to that Guccifer 2.0 login.)

Yet what Guccifer had access to was clearly broader than just the DNC. None of the first documents he posted showed up in WikiLeaks’ DNC email dump, and in fact, many of them eventually showed up in John Podesta’s emails, which were released much later. Additionally, on June 27, Guccifer emailed the Smoking Gun’s William Bastone a link to a password-protected post on DCLeaks.com that contained phished emails and documents from Clinton staffer Sarah Hamilton. (DCLeaks had not yet publicly posted any material related to the election.)

On July 6, Guccifer 2.0 posted his first documents that would eventually be found in the DNC emails. The New Yorker’s Raffi Khatchadourian speculates, based on some comments Guccifer made to journalists at the time, that Guccifer or his handlers were frustrated that WikiLeaks was taking too long to actually post the DNC material and were threatening to spoil Assange’s exclusive. (A week later, Guccifer would send documents to the Hill’s Joe Uchill, writing that he was doing so because the press was “gradually forget[ing] about me,” and complained that WikiLeaks was “playing for time.”)

All the while, Assange and WikiLeaks were working to prepare their database of DNC emails, with the apparent goal of publishing them before the Democratic convention began in late July. It’s unclear how they set that goal. Assange would later tell Khatchadourian that he originally had a deadline of July 18 to release them, but “we were given a little more time.” (It’s unclear, though, who gave him more time, and Assange later disputed the accuracy of the recorded quote.)

Finally, on July 22 — the Friday before the convention — WikiLeaks posted those thousands of DNC emails and attachments online. They revealed that many DNC members privately spoke of Bernie Sanders with disdain, drove DNC Chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz and other top staffers to resign, and overall made an ugly start for the Democratic convention. Though Assange remained mum on his source, Guccifer 2.0 jubilantly claimed credit in a tweet:

@wikileaks published #DNCHack docs I’d given them!!! #HillaryClinton #DonaldTrump #BernieSanders #Guccifer2 https://t.co/TXFAySUKWw

— GUCCIFER 2.0 (@GUCCIFER_2) July 22, 2016

The DNC leaks proved to be just the beginning. News soon broke that the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) had also been hacked, and on August 12, DCCC documents started showing up on Guccifer’s WordPress site. Guccifer also sent the DCCC’s internal turnout model data to Florida Republican Party operative Aaron Nevins, who was positively thrilled to receive it. “Holy fuck man I don’t think you realize what you gave me,” Nevins wrote in a DM. “This is probably worth millions of dollars.” Nevins soon put it online on his anonymously run blog.

Then DCLeaks got in the game. On August 12, the site posted a few emails from some little-known Republican state party aides, and from campaign advisers to Sens. John McCain (R-AZ) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC), both of whom were known as Russia hawks. In September, the site’s anonymous administrators sent Colin Powell’s phished emails to reporters, revealing his candid assessments of both Clinton (“greedy”) and Trump (“national disgrace”).

DCLeaks then posted phished emails from Ian Mellul, an Obama White House staffer who had volunteered for Clinton. The Mellul documents included a picture of Michelle Obama’s passport and a months-old audio file in which Hillary Clinton said Sanders’s young supporters were “living in their parents’ basement.” Longtime Clinton ally Capricia Marshall’s phished emails came next.

Many of these disclosures caused brief stirs, but what everyone was really waiting for was the next WikiLeaks dump. Roger Stone, the Trump associate, claimed that he knew Assange had something huge on the way and speculated it would involve the Clinton Foundation.

Carl Court/Getty Images

Carl Court/Getty ImagesAssange himself told Fox News back on August 24 that his team had “thousands of pages of material” and was “working around the clock” to prepare it for publication. By early October, there was still nothing from WikiLeaks, but Stone continued to hype an imminent release, saying “an intermediary” who’d met with Assange said “the mother lode is coming Wednesday.”

The “mother lode” instead came two days later, on Friday, October 7, when WikiLeaks posted its first batch of Podesta’s emails. The site would continue to post them, in batches, up through the election. Earlier on that very same day, the US government officially attributed the hacking effort to the Russian government, and the Donald Trump Access Hollywood tape hit the news.

In the end, the 2016 election was close, decided by just over 1 percentage point in three Electoral College states. And whether or not the email leaks were sufficient to swing the outcome, they certainly were effective at keeping the words “Hillary Clinton” and “emails” in the headlines throughout the campaign’s final stretch.

Trump associates tried to get in touch with hackers or leakers at least six separate times

During the campaign, it was clear enough that Trump was unusually friendly to Russia, and that the Russian government interventions seemed aimed at trying to help his electoral chances at the expense of Hillary Clinton. But after the election, more and more attention became devoted to whether Trump associates and Putin’s government coordinated to intervene in the campaign in some way. And on March 20, 2017, then-FBI Director James Comey publicly confirmed the FBI was investigating just that topic.

No one has produced a smoking gun demonstrating clear involvement just yet. But this isn’t mere idle speculation, either — there are at least six instances in which Trump associates tried to get Russian dirt or communicated with hacking and leaking figures. The first of them was what initiated the FBI investigation into the Trump campaign and Russia to begin with:

#business pic.twitter.com/NvlHAeUKdV

— George Papadopoulos (@GeorgePapa19) October 25, 2017

1) The Papadopoulos tip: Fancy Bear’s phishing campaign targeted Clinton staffers and Democrats in large numbers in March and April 2016, but the hacks remained publicly unknown for months afterward. Yet it was very early indeed — on April 26 — that Trump foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos got his tip about what was coming.

As described above, the tip was from a source Papadopoulos understood to have Russian government connections, professor Joseph Mifsud. Mifsud specifically said he’d gained his information from traveling to Moscow and meeting high-level officials there. And he said Russia had “dirt” on Hillary Clinton — and, specifically, thousands of emails.

We don’t yet know whether he told others in the Trump campaign about what he’d heard. But it seems highly likely that he did. He was a young adviser eager to impress campaign higher-ups. And we already know he drunkenly bragged about his inside info to an Australian diplomat a few weeks later. (The Australians later told the FBI, which led the bureau to open the investigation.)

In any case, Papadopoulos was arrested last summer for making false statements to FBI investigators, cut a plea deal, and began cooperating with investigators. So whatever he did do with his tip, Mueller likely now knows it.

Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images

Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images2) The Trump Tower meeting: It was on June 3, 2016 — a little more than a month after Papadopoulos’s tip, but still before any news broke about Democrats having been hacked — that publicist Rob Goldstone emailed an acquaintance of his, Donald Trump Jr. Goldstone described some news from his clients Aras and Emin Agalarov, a father-son pair of real estate developers who’d done business with the Trumps:

The Crown prosecutor of Russia met with his father Aras this morning and in their meeting offered to provide the Trump campaign with some official documents and information that would incriminate Hillary and her dealings with Russia and would be very useful to your father.

This is obviously very high level and sensitive information but is part of Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump – helped along by Aras and Emin.

Don Jr. enthusiastically accepted the offer, and Goldstone arranged a meeting six days later, on June 9. The Trump delegation included Don Jr., Paul Manafort, and Jared Kushner. They met Goldstone, Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya, Agalarov company executive Ike Kaveladze, Russian-American lobbyist Rinat Akhmetshin, and translator Anatoli Samochornov.

Once the existence of the meeting became public, all parties involved claimed it was a dud, resulting in nothing of consequence. But the timing of the meeting is strange. Three days later, Assange announced he’d received emails related to Hillary Clinton. Two days after that, the DNC announced it had been hacked and blamed Russia.

Goldstone saw an article about that and emailed it to Emin and Kaveladze, writing that the news was “eerily weird” considering what they’d just discussed at the Trump Tower meeting. Guccifer 2.0 began posting the day after that.

3) The Cambridge Analytica CEO’s contacts with WikiLeaks: Cambridge Analytica is the Steve Bannon-tied firm that did digital work for the Trump campaign and has been in the news of late.

Bryan Bedder/Getty Images for Concordia Summit

Bryan Bedder/Getty Images for Concordia SummitAnd last year, we learned that Cambridge’s CEO, Alexander Nix, had twice contacted WikiLeaks on the topic of hacked emails.

Nix says that in “early June,” after he learned of Assange’s claims to have Hillary Clinton-related emails, he reached out to Julian Assange to ask for an advance look at those emails. He says Assange turned him down.

Then in August, after Assange had posted the DNC emails, Nix emailed Cambridge employees to say that he’d recently reached out to Assange again, offering help at organizing the DNC material on WikiLeaks. He said he hadn’t yet heard back. Both Nix and Assange have said these overtures didn’t go anywhere.

4) Donald Trump Jr.’s contacts with WikiLeaks: Then, separately, Donald Trump Jr. had some communications with WikiLeaks through the group’s Twitter account toward the end of the campaign.

As best we know, WikiLeaks began the communication, DMing Don Jr. to tell him that they had guessed the password to a new “PAC run anti-Trump site,” PutinTrump.org, that was about to launch. “Any comments?” the group asked. Trump Jr. answered: “Off the record I don’t know who that is but I’ll ask around. Thanks.”

Then on October 3, 2016, WikiLeaks DMed Don Jr. again, asking him to “comment on” or “push” a story that Hillary Clinton had once said she wanted to “just drone” Assange. Don Jr. answered, “Already did that earlier today. It’s amazing what she can get away with.”

He then followed up with a question: “What’s behind this Wednesday leak I keep reading about?” This was at the height of chatter that WikiLeaks had a major batch of anti-Clinton material ready. However, there is no indication that WikiLeaks answered this question from Don Jr. or gave him any advance information that it was Podesta’s emails that were coming. The group sent him a couple more messages, but there are no more known responses from Don Jr.

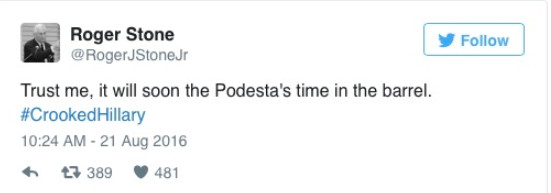

5) Roger Stone’s several contacts with both Guccifer 2.0 and WikiLeaks: Roger Stone is a longtime Republican operative with a reputation for dirty tricks and a decades-long relationship with Donald Trump. Stone was only an official Trump campaign adviser briefly, departing the operation in early August 2015 after clashing with other staffers. But he remained in Trump’s orbit and, to some extent, in communication with the candidate himself afterward.

Both in public and in private, Stone was fixated on the hackings and leaks.

One associate of Stone’s claimed to the Washington Post that at some point in the spring of 2016, before news of the hackings broke, Stone said he’d learned from Julian Assange that WikiLeaks had obtained emails that would hurt Democrats. (Stone denies this.)

Joshua Blanchard/Getty Images

Joshua Blanchard/Getty ImagesThe initial leaks from Guccifer 2.0 and WikiLeaks were posted in June and July. On August 4, Stone emailed fellow ex-Trump adviser and longtime associate Sam Nunberg: “I dined with Julian Assange last night,” according to the Wall Street Journal. (Stone says this was a joke and flight records prove he wasn’t in London then.)

The day after that email, on August 5, Stone penned a Breitbart article in which he took Guccifer’s story about being a lone hacker who stole the DNC emails at face value and argued Russia probably wasn’t responsible. He also tweeted that “Julian Assange is a hero.”

Three days later, on August 8, Stone started publicly claiming to have inside information. “I actually have communicated with Assange,” he said. “I believe the next tranche of his documents pertain to the Clinton Foundation but there’s no telling what the October surprise may be.”

A few days after that, Stone began tweeting at, and eventually DMing with, Guccifer 2.0 (who, again, has reportedly been identified as a Russian intelligence officer). Some of these DMs later leaked, leading Stone to post what he claimed was their full exchange. The posted messages are mainly friendly chitchat and not particularly substantive.

On August 21, Stone tweeted an odd prediction: “Trust me, it will soon the Podesta’s time in the barrel. #CrookedHillary.” Many would later point to this — which came months before the Podesta emails became public — and ask whether Stone had advance knowledge of the Podesta email leak. (Stone himself would later claim that since this came in the midst of a scandal surrounding Stone’s old friend Paul Manafort’s Ukraine work, he was merely predicting “Podesta’s business dealings would be exposed.”)

As October began, Stone took on a new role — as WikiLeaks’ hype man. He again claimed inside knowledge, saying a “friend” of his met with Assange and learned “the mother lode is coming Wednesday.” He tweeted: “Wednesday @HillaryClinton is done. #Wikileaks.” And when nothing came on Wednesday, Stone tweeted, “Libs thinking Assange will stand down are wishful thinking. Payload coming. #Lockthemup.” Assange published the Podesta emails two days later.

Immediately, there were questions about whether the garrulous operative had been involved, which eventually spurred WikiLeaks to tweet that the group “has never communicated with Roger Stone.” The Atlantic later reported that Stone DMed the WikiLeaks Twitter account afterward, complaining that they were “attacking” him. “The false claims of association are being used by the democrats to undermine the impact of our publications,” WikiLeaks responded. “Don’t go there if you don’t want us to correct you.” Stone shot back: “Ha! The more you ‘correct’ me the more people think you’re lying. Your operation leaks like a sieve. You need to figure out who your friends are.”

What to make of all this? Stone was obviously in contact with two of the key leakers, and his own public statements show that at one point he wanted people to think he had an inside line on WikiLeaks’ plans. However, he’s repeatedly denied any inside knowledge or involvement, and we haven’t seen any clear evidence that he truly had such knowledge.

In any case, we might learn more from Mueller’s probe soon enough. “They want me to testify against Roger,” Sam Nunberg said this year, referring to the special counsel’s team. “They want me to say that Roger was going around telling people he was colluding with Julian Assange.”

6) Peter Smith’s hunt for Hillary’s deleted emails: Last but certainly not least, there is one more email-related subplot to the 2016 campaign — and it’s a weird one.

Brooks Kraft/Getty Images

Brooks Kraft/Getty ImagesThis one involves a separate set of emails: When word got out that Hillary Clinton had used a personal email account for all her work at the State Department, she agreed to hand over the work-related emails on that account to government investigators. But it turned out that she had previously deemed about 32,000 emails (about half of the total) to be “personal” rather than work-related, and deleted them.

Conservatives like longtime Republican operative Peter Smith didn’t take Clinton’s explanation for why she deleted the emails at face value and questioned whether they could have contained scandalous behavior or criminal evidence. Their number included GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump. “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 [Hillary Clinton] emails that are missing,” Trump said at a July 27, 2016, press conference. “I think you will probably be rewarded mightily by our press. Let’s see if that happens. That will be next.”

It was around this time that Smith began an unusual project. He assumed that Clinton’s email server had been hacked and that her emails must be out there somewhere, on the “dark web.” So he reached out to computer experts and conservative activists, hoping to assemble a team that would track down those emails.

Smith didn’t work for the Trump campaign. But he is said to have repeatedly claimed to be in contact with Michael Flynn, who was advising Trump. One recruiting document Smith sent to cybersecurity expert Matt Tait contained the subheader “Trump Campaign (in coordination to the extent permitted as an independent expenditure).” It then listed several names: Steve Bannon, Kellyanne Conway, Sam Clovis, Flynn, and Lisa Nelson. (Bannon and Conway have denied any involvement. The other three haven’t commented.)

Eventually, Smith gave his version of what happened to the Wall Street Journal’s Shane Harris. He said his team found five hacker groups who said they had Clinton’s emails, of which two seemed to be Russian. “We knew the people who had these were probably around the Russian government,” Smith said. However, he went on, he couldn’t determine whether the emails were authentic, so he ended up just advising the hackers to give them to WikiLeaks. No such emails have ever surfaced. Smith — 81 years old and in poor health — killed himself in May 2017, 10 days after speaking to Harris.

Smith’s effort appears to have failed. But Smith admitted he had tried to get stolen documents from groups he understood to be Russian government-tied. And then there is the question of Michael Flynn’s role — particularly since, per Harris’s sources, there are intelligence reports that say Russian hackers discussed how they could get leaked emails into Flynn’s hands. Much remains murky about this situation, but Flynn is cooperating with Mueller’s team as part of a plea deal, so the special counsel likely now knows whatever he does.

Mueller will likely bring charges in the email hacking matter. But against whom?

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesLast November, the Wall Street Journal’s Aruna Viswanatha and Del Quentin Wilber reported that the Justice Department had identified more than six Russian government officials involved in the DNC hack and was considering bringing charges.

Interestingly, though, the report claimed that special counsel Robert Mueller had chosen not to take over the DNC hack investigation because it was “relatively technical” and had already “been under way for nearly a year.”

That appears to have since changed. Both NBC News and the Daily Beast reported in March that Mueller had now taken charge of the email hacking investigation. And the Washington Post reported in January that Mueller had added “a veteran cyber prosecutor,” Ryan Dickey, to his team. (Credit to Marcy Wheeler for flagging this point.)

So it’s a pretty safe bet that Mueller will bring some charges related to the email hackings. And judging by his past indictments, he’ll also use them to tell a story about what exactly happened, to the extent he can. There is, after all, a good deal we still don’t know — for instance, how, exactly, did the DNC and Podesta emails get from the hackers to WikiLeaks?

It’s important to remember that this is all just what we know about — there could be more that is still not public. It is certainly possible that several of their contacts with real or purported leakers and hackers listed above went nowhere, but it’s a bit harder to believe that all six of those separate contacts resulted in nothing of consequence.

Mueller has already gotten three people tied to Trump to plead guilty and cooperate with the investigation. What is he getting from George Papadopoulos, who got the earliest known tip that the Russians hacked the emails? What is he getting from Michael Flynn, who may have been tied to Peter Smith’s effort to get Clinton emails from Russian hackers? What was he getting from Rick Gates, who was Paul Manafort’s right-hand man both before and during the campaign?

All three men have pleaded guilty, and we haven’t seen any of the fruits of their cooperation yet. They may be providing Mueller information about the hacked emails, and they may not. But it’s safe to say they’re telling Mueller a good deal that’s of interest — and eventually, we will find out what.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png