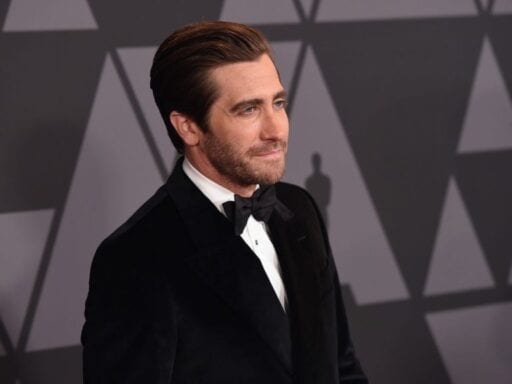

“If Gyllenhaal is seen in a community, he is usually in a t-shirt, a squared shirt, and inadvertent jeans.”

It’s a unique sort of suffering to be enamored of a celebrity — particularly if that celebrity has had no books written by or about them to provide an in-depth look at their glamorous and complicated life.

That is sort of the short explanation for how I came to purchase, two years ago, a Kindle-only book called Celebrity Biographies — The Amazing Life of Jake Gyllenhaal, written by an author named Matt Green, retailing for $2.99 and beginning with the sentence, “Jacob Benjamin or Jake Gyllenhaal is an American actor.”

The book contains many other beautiful sentences, most of which make much less sense than the first. “You always get the imprint that Jake Gyllenhaal treks to the beat of his own heart,” Green wrote. “Gyllenhaal is a peculiar type, and his characters reveal that; finding recognition with trendy flicks and jittery toll.” What does it mean? I have no idea! I don’t care! Two-thirds of the way through the book, it is explained that Jake Gyllenhaal’s “latter name” is pronounced “Jill-en-hall,” and that he has “a sportsperson’s body.”

According to Green’s Amazon author page, he is “an international best-selling author who writes about celebrity figures and their real stories” and lives with his wife Kate in London. He’s written similar Kindle-exclusive “books” about Denzel Washington, Channing Tatum, Justin Bieber, Katy Perry, Tyra Banks, and Kit Harington, among others.

For at least six months of 2017, I attempted to contact Green, which I’ll admit I knew was a fool’s errand before I even started. I emailed a Matt Green who is a cryptographer at Johns Hopkins University, a Matt Green who walked around New York City, a Matt Green who is a British comedian, a Matt Green who is an engineer, and finally, a Matt Green who has written a professionally published travel guide to London and works at a radio station. The final Matt Green replied to my initial email saying he was the Matt Green I was looking for, which prompted me to ask him for an interview. But it turned out that, contacted again, he did not think he was the Matt I was looking for.

It’s probably obvious to you that Matt Green is a pen name, but I had to try!

Matt is not singularly interesting anyway. There is also a writer who goes by Chas Newkey-Burden and has written Kindle biographies of Taylor Swift (“a bewitching young lady of contrasts”), as well as Amy Winehouse, Stephenie Meyer, and Adele, among others.

There’s Chris Dicker, author of a biography of Angelina Jolie in which he wrote, apparently sincerely, citing Alex Jones, that Jolie had been brainwashed by the United Nations, and that “just because Angelina Jolie packages war crimes, offensive invasions, funding rebels to destabilize regions and overthrow governments as ‘humanitarian’ does not make it so.”

And there’s the nonexistent Gregory Watson, whose author bio includes a “Man Writing in Coffee Shop” stock photo. For only $1, I purchased his The Inspirational Life Story of Paul Walker: The Golden Boy With a Heart of Gold.

“Paul Walker was more than just a handsome guy who did acting for a living. He was truly one of the good ones, who used their popularity to help others in need. His legacy will definitely live forever,” Watson writes. Also, “a lot of girls might have swooned on him in school.” Chapter five is a compilation of “inspiring quotes” from Paul Walker, including, “You know, all that really matters is that the people you love are happy and healthy. Everything else is just sprinkles on the sundae,” which I admit is nice; and, “Life’s too short. And the biggest curse is falling in love with somebody,” which I’d like to point out is absolutely a horrible thing to say.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13697598/51FMzsCyd_L.jpg)

The books themselves are not so important, but they feel already like an odd little relic of our times — objectively poorly made things, designed for money, reliant on the fact that curious people look for things in search bars and will maybe turn over a few dollars for something that appears to serve their needs. They’re made with no input from the gatekeepers of the publishing industry and don’t warrant the interest of the platform that hosts them (reached for comment, Amazon had nothing to say).

If they are breaking any particular rules of law or platform participation, nobody seems to care at all. They are clearly for profit, but it seems impossible that the required labor was rewarded by very many sales. The internet-era commodity they’re most similar to, in spirit, is an algorithmically generated racist T-shirt — they exist, and we can see how, and we can sort of see why, but can we really? I wanted to know, so I started with the boring historical facts that allowed for their existence and worked forward to their glittering, ridiculous present.

How the Kindle Direct Publishing program works

All these celebrity biographies were created with the Kindle Direct Publishing program, in which any person can upload any text and sell it, basically. The program was launched in 2007, concurrent with the Kindle itself, and both quickly came to define their respective corners of the e-book landscape. Per the New Yorker, “by 2010, Amazon controlled ninety percent of the market in digital books — a dominance that almost no company, in any industry, could claim.”

Today, there are hundreds of thousands of Amazon-published titles, although, as the New Yorker reported in 2014, “half of all self-published authors make less than five hundred dollars a year.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13697626/51JnFHtmmlL.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13697628/51rQEI8HQAL.jpg)

In 2009, Amazon Publishing — part professional publishing house and part free-for-all platform — launched, further blurring the line between traditionally edited and self-published books. You can downloads millions of titles to your Kindle, many for as little as $1, or a monthly fee through Kindle Unlimited. “Amazon has successfully fostered the idea that a book is a thing of minimal value,” Melville House founder Dennis Johnson told the magazine at the time. “It’s a widget.”

Under the Kindle Direct Publishing program, authors get 70 percent of the profits and Amazon takes the other 30 percent, a reasonable split as far as independent e-publishing goes. The program has content guidelines, obviously, but they largely pertain to formatting and typos, and mostly assert fairly obvious things like “blank journals and coloring books are not suited for Kindle.” It appears many of these celebrity biographies tiptoe toward violating very few of the quality-specific guidelines, and only the ones lumped together under the “disappointing content” section. In Amazon’s point of view, “disappointing content” can be a variety of things, but the ones possibly relevant here are:

- Content that is freely available on the web

- Content that is poorly translated

- Content that does not provide an enjoyable reading experience

These are all fairly vague, and I can’t prove that translation had anything to do with the descriptions of Jake Gyllenhaal’s body, and also, while I thought all of my purchases were terrible pieces of writing, I did enjoy reading them.

The KDP guidelines say that authors are free to use pen names, “as long as it does not impair customers’ ability to make good buying decisions.” I assume that mostly means I’m not allowed to publish horror novels under the pen name Stephen King. (Steven King, maybe?) So I guess it’s fine that I can’t find Matt Green.

In any case, it is to Amazon’s benefit not to closely interrogate the works uploaded to the Kindle library, as it makes money on them. And, given the library’s size, it would be absolutely impossible to do so.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13697605/Screen_Shot_2019_01_17_at_2.17.05_PM.png)

The program does have a storied history of scams

Amazon has already quashed quite a few e-book scams. At first, users could download public domain books from sources like Project Gutenberg, upload them, and sell them to readers who didn’t know better. A policy change in 2011 put an end to that. In 2012, Gawker’s Max Read came across another good one: hundreds of thousands of books that were just compilations of Wikipedia articles with titles like “Celebrities With Big Dicks.” One author he found was just publishing random data sets like “The 2007-2012 Outlook for Tufted Washable Scatter Rugs, Bathmats and Sets That Measure 6-Feet by 9-Feet or Smaller in India.”

The Atlantic published a feature on the site’s rampant plagiarism problem in 2016, citing instances in which popular works of fiction were tweaked and renamed and uploaded as original, pointing out:

When a reader buys a self-published book, Amazon keeps 30 percent of the royalties and gives the rest to the authors — meaning the company makes money whether the book is plagiarized or not. A traditional publisher is liable if it puts out a book that violates copyright. But Amazon is protected from the same fate by federal law as long as it removes the offending content.

Notably, incidents of plagiarism were almost always caught by a reader, who then reached out to the rightful author. Unless a text is copied word for word, Amazon’s system is unlikely to notice. And plagiarism is more or less the only content problem it is likely to care about, because internet-age plagiarism is the only content problem addressed directly by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. (The law protects third-party platform providers like Amazon from liability, but only so long as they provide a system to receive takedown notices and remove copyright-infringing content quickly.)

There was a brief heyday for content-farmed books as well — books made up of random web content, organized around SEO-friendly keywords, and repackaged by contract workers. Even after Amazon started confronting these problems, some scammers just got smarter, coming up with new tricks to get stolen content into the Kindle Unlimited program, which deals out payments from a communal pot based on pages read.

Others engaged in “book stuffing,” a practice Sarah Jeong reported on for The Verge last year, writing that self-publishers briefly tried to falsely inflate their books to be thousands of pages long: “Some of the books would include multiple translations into several languages — all run through Google Translate. Others would include junk HTML code.”

All of this is now against Kindle Direct’s content guidelines, which should theoretically make it a place for quality, original writing.

Is selling badly written, factually inaccurate books about a person in any way illegal? Is it profitable?

Patrick Kabat, a First Amendment lawyer who has done work for the New York Times and HBO, tells me this is actually all exactly as it should be. This biography of Jake Gyllenhaal is unimpeachable.

“From the perspective of the way the internet has evolved and the way that Congress has allowed the internet to breathe, this is exactly what Congress intended,” he tells me in a phone call. “Congress created this zone where all this stuff could happen with the 1996 Communications Decency Act. Section 230 starts with this singing declaration of the virtues of the internet and why we need to basically not screw with it.”

Privacy laws that professional biographers and authors have to worry about don’t affect Amazon specifically because they’re being published online. Amazon doesn’t have the legal responsibility a publishing house would have, and it’s in the clear as long as it sets up the DMCA-mandated method to submit copyright infringement takedown requests. The law was “already friendly” to celebrity biographers, Kabat says, because celebrities are public figures, and to be sued for defaming a public figure, you can’t just be wrong about the facts — you have to be willfully lying or recklessly disregarding obvious information.

“As long as it’s online, Amazon can’t be sued under any privacy torts,” he says. “So it’s unsurprising that all of these things flood Amazon. Amazon has no reason to be kicking lots and lots of people off. It has no reason to police this stuff for defamation or invasion of privacy, because it doesn’t have to.” He tells me these people are here and not at a publishing house not just because it’s easier but because “no one in New York would have them.”

Essentially, the barrier to publishing these books is even lower than the barrier to publishing something like a “100% Unauthorized Biography” of a boy band member with tear-out photos.

Most of these books have fewer than 100 customer reviews, and despite what their author bios say, I couldn’t find them ranked on any best-seller lists. Amazon has said that “almost 40” self-published authors have sold more than a million e-books in the history of Kindle Direct, but that’s out of hundreds of thousands.

It’s possible this is a more profitable hobby than most, but if Matt Green was making 70 percent of $2.99 each time someone cared enough about Jake Gyllenhaal to download an obviously amateur biography of him, it would take him 48 sales to crack 100 bucks. And since the average professionally produced nonfiction book sells only 250 copies a year, and fewer than 3,000 copies ever, I do not feel optimistic about the likelihood that Green was able to pay himself even minimum wage for his time.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13697636/Screen_Shot_2019_01_17_at_2.24.06_PM.png)

I’m not sure how Jake Gyllenhaal would feel if he knew there was someone out there taking in a few dollars at a time from curious fans eager to read about his fashion choices (“If Gyllenhaal is seen in a community, he is usually in a t-shirt, a squared shirt, and inadvertent jeans,” Green writes, helpfully), but that is mostly my problem, as I’ve written about him in strange ways on the internet so many times that his publicist refuses to talk to me. In any case, Green’s biography of him is no longer available to purchase, and nobody will tell me why. (Amazon did not respond to an email asking why. Also, as I said, I have no idea how to contact Matt Green.)

Though this did not turn out to be some big crime ring, or whatever, it did turn out to be about money. Both “Chris Dicker” and “Gregory Watson,” purport to be interested in celebrities because of their ability to inspire and inform, specifically about becoming rich and beloved. “Successful people are not so by accident. They do something other people do not,” Chris Dicker writes, on his author page. “Chris Dicker hopes that you’ll find your path if you learn from those who are successful and create a certain meaning in life.”

“In my books, I aim to bring to my readers inspirational stories that are easy to read, simple, and to the point,” Watson writes on his. “The idea is to have my readers take home something that they can live by and in doing so better their lives.”

Kabat is sympathetic to my longing for contact with the probably fictional Matt Green, but he does not want me to be harsh. “Pen names have always been used,” he says. “They’re particularly typical of when people feel less free to speak.” Sure, but I don’t think they are worried about censorship; I think they are hiding on purpose for reasons other than 19th-century sexism. I think they are just trying to make some money off some garbage. I worry I am wrong.

“It may be harder to reach these people,” Kabat says. “But who really cares about these people?”

Author: Kaitlyn Tiffany

Read More