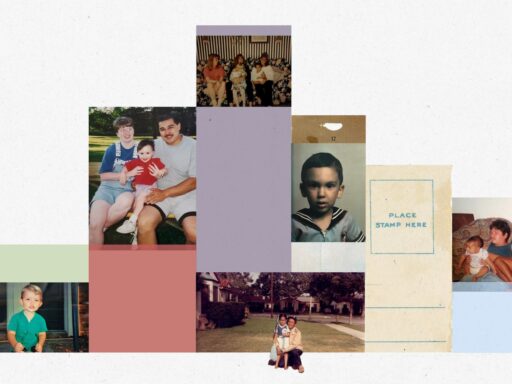

“I had to figure out the language to describe myself”: 6 mixed-race people on shifting how they identify.

This is part one of Vox First Person’s exploration of multiracial identity in America.

In 1993, the cover of Time bore a digitally rendered face, a supposed “mix of several races” that created a lightly tinted brown-skinned woman. “The New Face of America,” the headline proclaimed, heralded a future where interracial marriages held the promise of a raceless society of beige-colored people.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22236563/1101931118_400.jpg)

Almost 30 years later, the United States is getting ready to inaugurate its first female vice president, who is of Black and South Asian descent; the nation has already sworn in its first multiracial and Black president, Barack Obama. By 2013, 10 percent of all babies had parents who were different races from each other, and the number is only growing: In a 2015 Pew study, nearly half of all multiracial Americans were under 18 years old.

Demographically at least, Time’s cover story seems to have gotten it right. But inherent to their vision was a kind of multiracial utopia free of racial strife. This is a popular modern understanding of mixed-race identity. But multiracial people have long been targets of fear and confusion, from suspicions of mixed people “passing” as white under the Jim Crow system to accusations of not embracing one’s “race” enough — something Kamala Harris experienced on multiple sides this past election. Research has shown that, even today, monoracial people experience mixed people as more “cognitively demanding” than fellow monoracial people.

As the mixed population grows in size, it will likely continue to serve as projections for people to sort through America’s complex race relations. But what about the experiences of those who are actually multiracial? Studies illustrate a group of people who struggle with questions of identity and where to fit in, often feeling external pressures to “choose” a side. There’s evidence that mixed-race people have higher rates of mental health issues and substance abuse, too.

As Black Lives Matter protests swept the country in 2020, the issue of race came to the forefront of the national conversation. Everywhere, Americans engaged in deep discussions around the experience of Black and other non-white people in our country, including how race impacts the daily lives of all Americans in unequal ways.

Last year, Vox asked people of mixed descent to tell us how they felt about race and if the language about their identities had shifted over time. Among the 70 responses submitted, we read stories of people with vastly different experiences depending on their racial makeup, how their parents raised them, where they lived and where they wound up living, and, perhaps most importantly, how they look. But over and over again, we heard from respondents that they frequently felt isolated, confused about their identity, and frustrated when others attempted to dole them out into specific boxes.

Here are six selected stories, edited for concision and length.

Michael Lahanas-Calderón, 24, based in Berkeley, California

I’ve found terms to identify myself that feel somewhat comfortable but also somewhat unsatisfying. I don’t really know how to account for my mother’s background, which at best could be described as mestizo Colombian. Using the term “person of color” to account for it feels strange, just given what I see when I look in the mirror. But I also feel a kind of obligation not to let the complex mix of identities I inherited from my mother disappear into the whiteness inherited from my father. I don’t really know where that leaves me, to be honest, beyond using broader terms like Latino, Colombian-American, white-passing, mixed, or multiracial.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22223420/michael_collage_1.jpg)

Race didn’t come up a lot when I was growing up in suburban Ohio. Obviously, there was a Latino population there, but it wasn’t really a huge part of my life, beyond my mother in our home. It wasn’t like the way that Miami has the strong Cuban-American community. It was almost more an issue of whiteness and skin color being associated with some of those terms, which sort of changed the dynamic depending on the environment because I’m white-passing even with like a tan.

My mom went to great lengths to make sure that I could succeed in the US. When I was still quite little, my Spanish skills were actually developing at a better pace than my English ones. That is, until someone suggested to her that if my English skills didn’t improve, I would be at risk of falling behind the other kids and need speech therapy. This really spurred her to take serious action. She read countless books to me every night in English until I was a bookworm who sounded as Midwestern as the rest of my neighbors. To this day, out of all the things she remembers about my academic career, my high marks on English tests are some of the ones she’s proudest of. But I would be remiss if I did not mention the efforts of my mother to teach me about her and my identity, homeland, and culture, too. She always taught me to be fiercely proud of my blended heritage, and to never be afraid to share it with others.

At times it was pretty easy how well I had adjusted to suburban Ohio. I didn’t really think about the consequences of it until I was a little bit older, because it just got easier to not show that heritage. The shift away from that started in college, which was a much more progressive environment. I was sort of encouraged to explore that identity. We had a Latinx affinity group on campus and I think at times it was a little bit difficult for me to relate to others in the group. They were always welcoming, and it wasn’t that I didn’t feel included, but I think it was more that their experiences were so different from mine. The experience of being a Salvadoran American who is brown and grew up in, say, San Francisco with a pretty solid Latino community around them felt so wildly different from a white-passing, half-Colombian, half-American person growing up in suburban Ohio. We didn’t really have a lot in common beyond the shared language.

It’s always been important to me to recognize both parts of my heritage. But I suppose the only one that really felt like it needed exploring was my Colombian side, because I was always within the dominant side of mainstream American culture. I think that at times it almost felt easier, like everyone encourages you to kind of fall into that mainstream culture and assimilate. If you don’t have that kind of connection to a first-gen or community of immigrants who are actually actively forming a social group, it’s very easy to let one side of your heritage — the one that’s not the dominant culture — slip away. It’s kind of one of my regrets, to be honest, and I’ve made an effort as I’ve gotten older to embrace that again.

Abbey White, 29, based in Brooklyn, New York

Right now, and this may change, I identify as a mixed-race Black person. But initially, I identified as bi-racial. I felt like growing up in the environment that I was in, an Ohio suburb, it was very clear to me that I was Black and I was mixed, but when I moved to New York, that dramatically changed. I got a lot of people not really being able to recognize me on sight. I’ve had to deal with an ethnic ambiguity that I never had to deal with before. So I had to figure out the language that I wanted to use to describe myself.

I think part of that stems from the fact that when I grew up, my dad, who is Black, wasn’t really in my life, so a lot of my Black identity came from the Black people that my mother worked with and the neighborhood that I lived in. But also, my family was so white and, frankly, for as much as I love my mother, racist. My grandfather would not be in the same room with her the entire nine months she was pregnant. He couldn’t even hold me for the first couple months of my life.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22239708/abbey_collage_1.jpg)

I sort of remember realizing my race when I was late elementary school age and I had gotten in trouble at my grandmother’s house. And I remember putting, like, baby powder on my skin and like trying to convince myself for whatever reason that I would not be as in trouble if I looked more like my mom.

I also felt this struggle to feel connected with Black people when I was growing up. I felt often like a conditional Black person, and I think there are some mixed-race Black folks that have a lot of anger about that. When I was younger, I did. But I’ve also come to understand that the idea of being “authentically” Black is literally a response to things like the one drop rule and this white supremacist idea of how we define race and mixed race, and Black identity being tied to sexual violence. So this reclamation of what it means to be Black is a byproduct of racism.

There are also privileges I have that other non-mixed Black people don’t. I am lighter-skinned. I might not be white-passing, but I can pass as something else. Because for some people, I’m “racially ambiguous,” what has happened is I have found myself in situations with white people who feel very comfortable saying things that are not okay. It’s this sort of, “you’re not like other girls.” Like my grandfather wouldn’t even be in the same room with my mom, but then once I came into this world and they realized, “oh, she’s a baby and race has nothing to do with this,” it wasn’t, “we see Black people as human beings and we respect them.” It became: “You’re our Black child. And you’re the exception to the rule.”

It’s weird being in places with people who try to make you the exception to the rule, and it makes me want to double down. Because I’m not an exception. I think that that has really made me embrace this idea of I am Black. I’m mixed, but I’m Black.

Josh S., 24, based in Brooklyn, New York

I identify as multiracial. There hasn’t really been another term that’s resonated with me in the same way. I like breaking it down a little — my family is white, and then on my dad’s side, I have family in Japan. I think the change in identity from when I was younger is that I actually have the language to describe who I am, which I lacked back then. I only knew that I wasn’t wholly white, but that it was thrown into pretty sharp contrast because I grew up in a town that was like 99 percent white.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22224043/joshua_collage_1.jpg)

Being thought of as Asian was definitely foisted onto me. Because I did relatively well in school, there was a lot of like, “Oh, the Asian got a good math score.” There was something that felt off about that. Later I realized that, well, my race has absolutely nothing to do with how I perform in school. They were creating this entire persona and this cruel game out of where my grandmother came from. Toward the end of high school, there was just this resentment of that part of myself. Not necessarily that I wanted to stop being mixed race, but that I just kind of wanted being treated differently to go away.

Going to college in Washington, DC, gave me that opportunity. Hardly anyone could tell that I was like anything but white. And so for a couple of years there, I got to experience the world without micro-aggressions and the casual racism that I had growing up. I was just able to coast by on whiteness, which was, coming from where I was, a bit of a relief. Of course, this was an environment that I didn’t fit into for a number of other reasons, even if I could present and act white. There was a substantial difference from my rural, more middle-class upbringing as opposed to the white wealthy upbringing many of my peers had. Even being white, it was a different kind of white.

I think after a couple of years of wrestling with, “I’m never going to be white enough or rich enough to fit in with this,” brought me back to trying to reflect more on my grandma and her heritage and my father’s experience. My father identifies as a person of color, but his response to it, especially as he had children, was to sort of push it to the side. For all intents and purposes, my brother and I were raised with no connection to being Japanese, and he didn’t really do anything to encourage it. His experience growing up in rural Minnesota being called every racial slur under the sun, I think there’s trauma there. I think my parents operated to try and raise us to have a better and easier life.

How I identify, and being non-binary, it’s something I’m grappling with constantly. This isn’t to say that my experience is harder than other people’s. But there is that constant vigilance to not, you know, slip into comfortable. As a masculine, white-passing person, life would probably go by fine for me. It’s having that self-awareness and continuously working on the awareness to keep pushing against white supremacy and patriarchy wherever it shows up.

Thema Reed, 27, based in Austin, Texas

I consider myself to be Chicana and Black. On my dad’s side, I’m what a lot of Mexican people would call Hispanic, which is a pretty generic term. And then my mom is a Black woman who was adopted and raised by a white woman when she was 14. She is still really connected to her Black roots, and we have a big Black family that we’re so very connected to. But there’s kind of a few different layers in there.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22223422/thema_collage_1.jpg)

I’ve always identified as both, but I definitely felt a lot of pressure to identify or present myself in different ways throughout my life. I’ve heard some Black people say, “Well, mixed people aren’t actually Black.” And I think that a lot of that comes from a feeling that mixed people can maybe turn off their Blackness sometimes or that mixed people have features that may give them privileges. I would also hear things like, “Oh, well, it’s a shame that Thema is not more light-skinned.” It’s like, I’m not Black enough, but I’m simultaneously too Black, you know?

At the same time, people who maybe aren’t Black or who aren’t mixed look at me as a Black woman. It is hard for me to get people to understand that just because I don’t look Chicana doesn’t mean that I’m not. In New Mexico, Chicana culture is such a big thing there, I think that most people in New Mexico identify with it to some extent. So I didn’t face as much judgment for not being “Chicana enough” as I did until I moved away.

When I was in college, I went to Howard, and that really changed the way that I was able to identify with the Black part of me. I had never been in a place where there were so many Black people that looked so many different ways. There were so many mixes, and with so many different countries, so many different socioeconomic backgrounds. I really felt really accepted and loved for the first time.

I think I kind of really grew up as a chameleon and I learned how to code switch and communicate with a lot of different people when I was really young. I think that there’s something special about that. But I think it does come with a cost. I really experienced it from both sides — I’ve experienced colorism, I’ve experienced people saying, “Well, you’re not Black and you’re not Mexican enough.” I feel really strongly connected to both, but at the same time, sometimes I feel like I belong to neither.

Jaymes Hanna, 35, based in Washington, DC

I am a mix of Brazilian and Lebanese descent. I think my identity is very much like a Venn diagram, where I keep moving around those various circles and the overlap keeps changing all the time. The one thing I have kept constant is some sense of mixedness. If I have to put myself in a commonly recognized box, it would be Latino.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22223559/jaymes_collage_1.jpg)

I grew up in inner-city Philly, in a predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood. I very much connected to those communities and those cultures and tried to do everything to highlight my Latino-ness — from clothes to manner of speech. My father being Lebanese, I think he experienced some prejudices when he moved to the country, given the long history with our region, and was never eager for me to play up that part of my heritage and culture. So growing up in a predominantly Brazilian household, it was just easier to move forward with that, which is another reason why I think I’ve identified as Latino more predominantly.

As I got older and progressed into the engineering world, I sort of shifted. That was probably the first time I was in a very white-dominant setting. I did a lot of stuff to play my Latinoness down until I left for the social impact field where I thought I could sort of reconnect with the Latino pieces of me.

Even now, there’s elements of my identity that don’t get represented so clearly to someone who sees me as an early- to mid-career professional, especially if they’re white. I do get, “Oh, you’re not bad!” especially if I talk about being Latino, growing up in that neighborhood and going to an inner-city public school where I’m treated a certain kind of way by teachers and the powers that be. It’s always frustrating or disappointing because when I hear that, that very much means to me that you don’t see me. Like you want to be comfortable with me in a certain box. You’re not interested in the actual things that have shaped me to be who I am today.

I’ve been called ethnically ambiguous by more than one person. It makes me feel like a blank slate sometimes. But in some ways, it is kind of cool because I feel like if someone’s trying to identify with you or call you one of them, that creates openness to actually connect with people.

Kristina, 43, based in Los Angeles, California

I identify proudly as a multiracial woman and as a woman of color. This is because the world sees me as a woman of color. I’ve never been perceived as a white woman.

I only recently became confident that I could just, in some circumstances, say “I’m Filipino.” I don’t always have to qualify the basis of my identity to everybody. That is very new for me because people always felt the need to say, “You’re only half,” or remind me that I’m also white. But as I’ve gotten older, and just with more recent conversations about race, I’ve come to realize that I don’t care anymore. I am Filipino, I am white. I don’t always have to say all of my mixed percentages to everybody.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22223624/kristina_collage_1.jpg)

When I was younger, I would always qualify everything by saying, “I am half white.” I didn’t want people to think I was trying to co-opt any identities or infringe on anyone’s spaces. In college, friends would take me to Filipino student group meetings, and I just always felt like an imposter, like I didn’t have a right to be there. I don’t know if that’s true or not to this day. I still don’t quite know my place sometimes. I just know I feel at home in the Filipino community with my Filipino family.

At the same time, I didn’t want to feel like that was denying my mom. Even though I don’t identify as a white person, I was raised by a white mom who has a beautiful history and life too. So I don’t like to discount that.

I sort of loathe the inevitable reductive discussions that pop up whenever a multiracial person comes up, whether that’s Kamala Harris or Bruno Mars. I just wish the world knew they don’t get to tell multiracial people how we identify. Each of our own experiences is incredibly unique, depending on who we are raised by, where we were raised, how we look.

I also wish people would stop portraying mixed people as so tragic. I grew up in the ’90s and every discussion about it was about how we were so tortured. It almost seemed like they were putting it out there as a cautionary tale about having multiracial children. But for me, most of the “negative” aspects of being mixed were external, not internal. I absolutely would not change being mixed for the world.

Author: Vox First Person

Read More