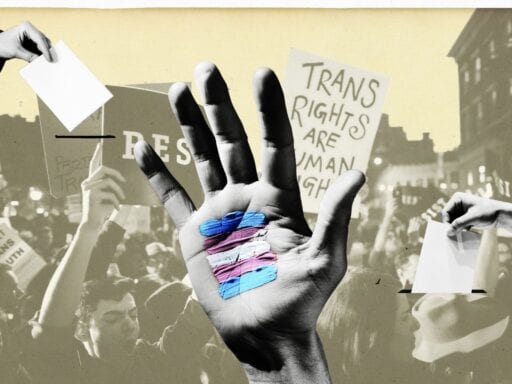

Trans people have always been disenfranchised. Voter ID laws are making the problem worse.

Last November, a trans woman was asked for identification when she went to her local polling place to vote in Cornelius, North Carolina. The poll worker had balked when the woman gave what the worker perceived was a masculine name, calling over the precinct’s chief judge to get involved and demand identification, according to the Charlotte Observer.

While the state had recently passed a voter ID law, it hadn’t taken effect yet. None of this was legal.

The woman was ultimately able to vote, but the incident and others like it underscore the shame and harassment many trans people endure to cast a ballot — and that’s if they can even cast one. Trans people who live in the 35 states with voter ID laws face challenges if they don’t have a form of identification that matches their gender identity. According to a February report from the Williams Institute, an LGBTQ research hub at the University of California Los Angeles, an estimated 260,000 trans people do not have an ID that correctly reflects their name and/or gender to use in the 2020 presidential election. With approximately 1.4 million trans adults in the US, this is a significant portion of the trans population.

While voter ID laws may be the latest barrier to trans people accessing the vote, they’re historically by no means the only one.

Most trans people have always lived at the margins of society and have faced social and economic difficulties — homelessness, incarceration, and institutionalization — that have long served as roadblocks to voting.

A lack of employment and housing protections throughout most of the country contributes to financial insecurity for trans people, particularly for Black and Indigenous trans women and other trans women of color. According to a 2017 survey by New York City’s Anti-Violence Project, transgender New Yorkers were more likely to have a college degree than the general population, but just 45 percent of them have full-time jobs. Overall, transgender workers are more likely to be unemployed compared to their cisgender counterparts, and 34 percent of Black trans women face housing insecurity compared to just 9 percent of non-Black trans people. Such instability can make the logistics of voting challenging.

“People tend to be more engaged politically when they’re stable, when they’re invested in a community,” Astra Taylor, whose 2018 book Democracy May Not Exist, but We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone is a deep dive into American disenfranchisement, told Vox. “All of these things compound when you are more likely to be poor, you’re less likely to own property, and you’re more transient. [They] make it really hard to register to vote.”

Systemic problems, coupled with discriminatory laws, have long limited the voting rights of America’s most marginalized — and trans people have faced disenfranchisement from all angles.

The history of trans voting rights

Many people are familiar with the more famous dates in suffrage history, even if the logistics are much more complicated than they seem: Black men, at least on paper if not in practice, gained the right to vote in 1869; white women did the same in 1920; and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 got rid of Jim Crow voting laws, giving many Black women the right to vote for the first time. But the history of trans voting rights is more amorphous and more difficult to define.

Anti-cross-dressing laws in many cities and jurisdictions made it difficult for trans people to simply exist openly in public before the 1960s. According to Susan Stryker, a trans historian and professor emerita at the University of Arizona, anti-cross-dressing laws started popping up in the United States in concert with the mass urbanization seen in cities like St. Louis, San Francisco, and Chicago, which were “undergoing really rapid demographic and economic transformation” in the 1840s.

“It wasn’t necessarily transphobia per se, but usually it was part of a broader suite of things that were imposing social order and good governance and morality,” Stryker said. “They were connected with things like ordinances against public drunkenness or nudity or lewd behavior, and often against prostitution.”

But while those offenses weren’t felonies on their own — in many states, felons can’t vote, or can only vote after their maximum prison term has expired or their probation is completed — they did attract attention from the police, which often led to further, more serious charges that potentially put a trans person’s right to vote at risk.

“What counts as a criminal is always political,” said Taylor, who noted that criminals in democratic societies, going back even to ancient Greece, were often denied the right to vote. “The disenfranchisement of felons in this country is, on one hand, a kind of very cold and calculating strategy led by Republicans to enforce their minority rule and to bolster their power. But it’s also this very old, timeworn idea that is deeply enmeshed in our culture and our collective unconscious.”

Though officially repealed in the late 1970s after protests by LGBTQ people and several significant legal wins, the anti-cross-dressing seeds planted in the mid-19th century took root and still exist in many places in the US today in the form of “walking while trans” laws, which allow police to stop trans women on the assumption that they are sex workers. A Black trans activist in Arizona was infamously arrested in this fashion in 2014, and an NYPD officer testified at a deposition last year that he would drive down the street looking for women with “Adam’s apples” to stop on suspicion of solicitation. Under the law in New York and many other states, discovery of a condom in a purse is sufficient evidence to arrest a trans woman on prostitution charges.

Much like the anti-cross-dressing laws, these are also not felonies, but more interactions people have with police can potentially lead to harsher charges, which can potentially lead to disenfranchisement. For example, Arizona has one of the stricter felony voting rights restrictions in the southwestern US, while New York state allows felons to vote only if their maximum prison term has expired or they have completed probation.

Because of this, Tori Cooper, director of community engagement for the transgender justice initiative at the Human Rights Campaign, told Vox that the fight for former felons to vote and the fight for trans voting rights are inherently linked — 21 percent of Black trans women will face incarceration at least once in their lifetime, a rate significantly higher than the general population.

Cooper pointed to the legal dispute in Florida over felon voting rights. After a statewide referendum in 2018 to restore voting rights to felons in the state, Republican lawmakers in Florida passed a law requiring felons to pay off any fees associated with their sentence before being allowed to vote, which critics liken to a poll tax. It was recently upheld in court, and now 774,000 Floridians, many of them from marginalized identities, have once again been presented with a roadblock to voting.

“We know that there are certain entities that are fighting tooth and nail to make sure that folks who have felonies can’t vote, no matter what the felony, and that’s terribly, terribly wrong. And it leads to further disenfranchisement, which leads to further marginalization,” said Cooper.

Voter ID laws and inconsistent gender change processes combine to marginalize trans voters

In 35 states, you need an ID to vote; 18 of those states require a photo ID. If you’re trans and your name and your gender don’t match your ID, you can be challenged at the polls like the woman from North Carolina.

Unfortunately, the solution to this roadblock isn’t as easy as a trans person walking into the DMV and asking for a gender marker change.

In fact, it wasn’t even possible for trans people to change their legal gender until well into the 1970s. A series of court battles in New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s failed to challenge administrative rules in the state that only allowed gender changes on birth certificates in the case of error. But a Connecticut state court ruling in 1975 began to move the legal needle on the issue, when it was decided that the state must demonstrate a significant interest in order to deny a name and gender change. Like anti-cross-dressing laws, rules and standards around legal name and gender changes for trans people differed depending on where a trans person was born.

“When we’re looking at voting while trans, we’re looking at the intersection of two different types of state laws: voter ID laws and name and gender change laws,” Arli Christian, campaign strategist with the national political advocacy department at the American Civil Liberties Union, told Vox. “In the past 10 years, we have seen improvement in gender change laws on the state level. We’ve seen laws move away from a medicalized model of trans identity where administrators would inappropriately request information about private medical procedures to get your documents updated.”

Up until the early 2010s, states that allowed gender changes on official IDs required proof that an applicant underwent gender-affirming surgery in order to change their gender marker. With the procedure often explicitly excluded from health insurance coverage and costing at least $20,000 out of pocket, that requirement put legal gender changes out of reach for the vast majority of trans people. Add to that the cruelty in requiring trans people to sterilize themselves just to get an ID that matches their identity and the fact that many trans and nonbinary people don’t want surgeries in the first place.

According to Christian, about 20 states now allow legal ID changes without a doctor’s note. However, nine states — Iowa, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma — still require proof of surgery in order for someone to change their legal gender. All of those states also have voter ID laws on the books, potentially opening up trans people to discrimination at the polls on Election Day.

“The most problematic states are when you have a state with a strict photo ID requirement, and on top of that, they have burdened burdensome policies for updating the name and gender marker on the ID,” said Christian. “That’s when you present a huge barrier for trans people in that state, and sort of coming together, those two things make a mess.”

After four years of attacks from the Trump administration — from the trans military ban to rolling back trans health care protections — the election is critically important for trans rights. And with so much on the line, as many trans people as possible need to be able to cast a vote this November. Their lives, livelihoods, and chances at stability may depend on it.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Katelyn Burns

Read More