Corey Robin on Thomas’s black nationalism and why more people should understand it.

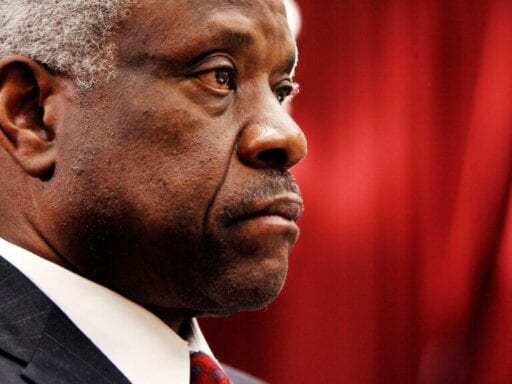

Most people have strong opinions about Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

At 71, Thomas has been on the court for nearly three decades and his views on everything from affirmative action to abortion rights to prison reform and voting rights have delighted the right and offended the left.

And then, of course, there’s the Anita Hill fiasco.

The truth, though, is that we don’t know all that much about Thomas apart from his public pronouncements. And if a new book by political theorist Corey Robin, called The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, is correct, it turns out Thomas’s worldview is more complicated than we thought.

Arguably the most reactionary member of the Court, Thomas is also, according to Robin, a bundle of contradictions. His position on affirmative action, for instance, is basically in lockstep with the largely white Republican Party. And yet Robin argues that Thomas has always been a “black nationalist” with a very coherent and fatalistic view of race in America. And it’s that skepticism about progress and the belief in black self-determination that pushed Thomas down the road to ultra-conservatism.

Thomas’s pessimism about race and politics, as described by Robin, captures a dilemma at the core of American life: if white supremacy is baked into the DNA of America, if it’s so deeply embedded in our culture and institutions, is there any hope of moving beyond it?

Thomas seems to think there isn’t, and it’s why he regards every attempt at using the law as a tool to redress inequalities as futile. His alliance with a conservative movement that is overwhelmingly blind to these realities makes for a strange marriage indeed; it also, oddly enough, aligns him with many progressives who share his grim view of racial progress in America.

Robin, a leftist who studies the history of conservatism, made a deliberate choice in this book not to critique Thomas but instead to understand what he believes and why he believes it. The result is a deeply instructive and fair look at one of the most important political figures in the country.

I spoke to Robin about the roots of Thomas’s philosophy, why his brand of conservatism is so emblematic of this moment in history, and why it’s important to understand Thomas even if you disagree with him.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

Let’s start with the most eye-popping claim of your book. You make a pretty convincing case that Thomas is — and remains — a “black nationalist.” What, exactly, does that mean?

Corey Robin

The core of black nationalism begins with a recognition that the destiny of African Americans cannot be accommodated by the American political system — that African Americans have a set of interests and a destiny that lies apart from the overall American experience.

The implications of this belief vary depending on who you ask. Sometimes it has meant looking outside the US to fulfill that destiny. Sometimes it has meant looking within the US, but within a kind of self-determining sovereign enclave, what is often called “the Black Belt.” More often than not, though, it has meant creating separate parallel institutions, building up the race with the understanding that African Americans aren’t going to leave America.

But the main idea has always been that African Americans could carve out some measure of autonomy if they disengaged from the dominant institutions of white America. And this is where Clarence Thomas has always located himself. He was very active as a younger man in leftist black nationalist movements, but he begins to move to the right in the early ’70s.

Sean Illing

And how do you trace Thomas’s thinking in the book? Are you looking at his early writings, his speeches, his activism?

Corey Robin

There are several really excellent biographies of Thomas, and if you read them closely, all of this stuff is there. Most of them detail his college years when he was extraordinarily active politically. Even among a group of young black men who were recruited to Holy Cross, he sort of stood out both for the depth of his commitment and the extensiveness of his involvement.

But what’s even more interesting is when you start reading his speeches and writings as he makes his right turn in the ’70s. And you can see how all of his black nationalist assumptions remain with him as he’s making that right turn, even when he’s a very visible member of the Reagan administration.

And of course I looked at his jurisprudence. What I discovered was a pervasive thread of race-conscious conservatism running throughout all of his judicial opinions

Sean Illing

Thomas’s opposition to affirmative action or really any attempt at improving race relations looks a lot different to me after reading your book. You argue that Thomas isn’t objecting to these things because he denies the underlying injustices but rather because he rejects anything that smacks of “white paternalism.”

Can you explain this?

Corey Robin

Thomas assumes that racism and white supremacy is ineradicable in America. It’s a permanent feature of the American condition. And the problem for him with contemporary liberal America, which he thinks really begins with the New Deal, is that white supremacy to a certain degree changed its spots but not nearly as much as most people think.

Sean Illing

And that means what, exactly?

Corey Robin

For Thomas, it means that there’s an assumption among white liberals that the job of the American ruling class through the state is to improve the lot of African Americans and to use the state to rectify these past injustices. And Thomas just doesn’t believe that it’s impossible to remedy these injustices, he also believes that the acts of paternalism end up perpetuating the injustices.

Sean Illing

How so?

Corey Robin

They perpetuate the conditions of black weakness and black victimization by making black people dependent. Now, Thomas doesn’t object to dependence as such; he thinks depending on white people means depending on a force that’s as arbitrary and as whimsical as the weather, and very dangerous and ends up weakening black people and destroying the kinds of habits and skills and virtues that black people depended upon and developed over centuries of subjugation and oppression.

Sean Illing

That perspective is crucial to making sense of his conservatism. In the book, you say that Thomas’s conservatism is “race-conscious,” but in a way that will seem strange to most conservative and even liberal readers. What does black conservatism mean to Thomas? And how does it square with his black nationalism, which I suspect a lot of people instinctively identify with leftist projects?

Corey Robin

It’s true that black nationalism has had very strong leftist elements and traditions, but there’s also very strong conservative elements focused on self-help and discipline going all the way back to Marcus Garvey and, some would argue, Booker T. Washington. I don’t have a dog in that fight, and I don’t make any claims about what black nationalism ought to mean. But it’s important to at least acknowledge that history.

One thing to understand about Thomas’s conservatism is that there’s a strong belief in patriarchy. He has said quite plainly that the salvation of the black race depends upon black men. This is one area where his conservatism and black nationalism converge.

And yet, unlike many conservatives, he’s not that much of an individualist because he’s very much rooted in black communalist traditions. And he doesn’t really believe in colorblindness. All of this distinguishes him from most white conservatives.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19273487/Enigma_of_Clarence_Thomas_cover_image.jpg)

Sean Illing

One of the strangest parts of all this is the fact that Thomas has managed to preserve his core black nationalist beliefs on the court while at the same time, as you put it, “remaining a hero to some of the most racist elements of the American polity.” Is this just a case of his supporters not bothering to understand what he actually thinks and why he thinks it? Or do many of them understand it and just don’t care?

Corey Robin

I think they haven’t bothered to understand what he thinks. It’s clear that most white conservatives just don’t see it. Even the best scholarship on the right just doesn’t touch this dimension of Thomas’s thought, at least not as far as I can tell. And this continues to be part of the paradox of Clarence Thomas. He’s probably the most well-known member of the court, everybody knows who he is, and yet no one really knows who he is.

Sean Illing

I think this is true on the left as well, but we’ll get to that. First I’d like to ask you how these background assumptions structure Thomas’s judicial philosophy. One of the contradictions you explore in the book is the fact that Thomas is an avowed originalist, someone committed to applying the Constitution as it was adopted in 1789, and yet he acknowledges that that Constitution was written by and for slaveholders.

Corey Robin

Well, the first thing I’d say is that Thomas’s originalism is pretty inconsistent, but let’s not get into the weeds on that. Here’s why I think originalism is important to Thomas and it’s partly for the reason you just mentioned: He sees it as a kind of permanent reminder of the constraints written into the Constitution under which African Americans have labored for over three centuries.

Thomas sees value in this, and he’s very upfront about it. It would be too strong to say that he would like to rewrite the Constitution as if it were a Jim Crow Constitution, but he really does believe in his heart of hearts that black people, particularly black men, flourished under the heavy yoke of subjugation that was Jim Crow.

And this is where his ideology is pretty straightforwardly conservative: he believes that under the conditions of extreme hardship, the strongest wills have a way of bashing their way through those constraints in order to overcome them, and he thinks this is what the African American community did when it was oppressed by the white majority.

Sean Illing

You say that “the story of Clarence Thomas is the story of the last half century of American politics and the long shadow of defeat that hangs over it.” This gets at the sense of racial despair a lot of people — on the left and right — feel right now. As the gains of the civil rights movement are eroding, as white nationalism subsumes the White House, it’s hard not to sympathize with Thomas’s pessimism about the possibilities of political progress.

Is that how you feel after writing this book?

Corey Robin

I didn’t need Clarence Thomas to convince me that the gains of the civil rights movement and the black freedom struggle had been cut back in a big way — that movement has been in reverse motion for quite some time. But engaging with Thomas did clarify for me how strong this ambient mood of racial despair is right now, and I think many people on the left think that that signifies the mark of progressive values.

But I don’t think that’s true at all. The beginning of the left tradition — and I say this as someone on the left — is the recognition that oppression can be undone and transformed. Oppression is the product of politics and it can be dismantled through politics — we risk forgetting this when we become overly pessimistic.

I hope wrestling with Thomas’s conservatism opens up a discussion across the country about where we think racial pessimism leads necessarily. Identifying the structures of oppression is critical, but it’s only constructive if we also identify the vulnerabilities of those structures. This is the job of the left and we’ll lose if we cease to do it.

Sean Illing

What sort of impact do you see Thomas having on the court — and the country — moving forward?

Corey Robin

For many years Thomas was a voice in the wilderness on the court, but that has changed in recent years. There are just more hardcore right-wingers with him on the Court. So he’s really having a moment. He is the most senior justice on the court. So that means that whenever he and Roberts are on opposite sides, he gets to assign the opinion.

The fact is, Thomas’s opinions matter now more than ever. And I would say that we’re in this very strange moment right now, particularly on the left, in which there’s a lot more attention being paid to questions of race. And a worldview like Thomas’s just isn’t interrogated seriously on the left, not as seriously as it should be.

I mean, this is the most powerful black person in the United States right now, and nobody knows the first thing about him. Don’t just assume you already know, because there’s a long history of that in this country, of white people just assuming they know the story of someone.

Thomas, whatever you think of him, has a fascinating story — and we all need to know it.

Author: Sean Illing

Read More