The Bernie Bro stereotype is reductive. But there’s a specific group of Sanders fans that pose a real problem for him.

It seemed natural to many that when Sen. Elizabeth Warren dropped out of the presidential race, she would endorse her longtime ally for Bernie Sanders for president. Yet she didn’t — and one reason, judging by her Thursday exit interview with Rachel Maddow, is anger at the way Bernie’s online supporters have behaved.

“I think there’s a real problem with online bullying and online nastiness. I’m not just talking about who said mean things; I’m talking about some really ugly stuff that went on,” she said.

The behavior in question ranges from angry Sanders fans tweeting snake emojis at Warren accusing her of being an anti-Sanders backstabber to online harassment of (generally female) Warren supporters. There have also been accusations that possible Sanders supporters published the home addresses and phone numbers of two women who worked for the Nevada Culinary Union after it produced a fact sheet critical of Sanders’s health care plan.

When Maddow asked if “it’s a particular problem with Sanders supporters,” Warren replied bluntly: “It is. And it just is. It’s just a factual question.”

Warren’s frustrations cut to the heart of a debate that’s been raging throughout the Democratic primary, but has come to a head since Biden supplanted Sanders as the race’s frontrunner on Super Tuesday. Observers have started assigning blame for the Vermont senator’s fall from grace — and one purported culprit, though certainly not the only one, are the antics of the “Bernie Bros.”

But the media’s obsessive focus on Bernie Bros — a term coined in 2016 to describe privileged white male Sanders supporters that doesn’t accurately describe his 2020 base — has obscured the real nature of the problem: a particular subculture among some Sanders fans that flourishes primarily on Twitter.

This group has coalesced around a loose group of left-wing media outlets that call themselves the dirtbag left, most notably the podcast Chapo Trap House. The dirtbag left promotes vulgar online attacks as a means of promoting left-wing politics, often through crass jokes in podcast episodes and on Twitter. (A recent Chapo episode involved hosts joking that Warren would have pretended to be Arab to join with the Flight 93 9/11 hijackers, making a crass sexual comment about Warren-sympathetic New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg, and a proffering a jokey, false theory that “Big Vaccine” and/or Bill Gates made up the coronavirus.)

And while it’s true the media can overreact to this kind of taunting, it really does seem to be hurting Sanders’s efforts to expand his coalition beyond his hardcore base.

Many mainstream Democrats see the behavior of Sanders’s dirtbag left fans as a reflection on the campaign and link their rhetoric to Sanders supporters’ harassment of Nevada Culinary Union staff (there is no evidence that Chapo fans are the ones responsible for the Culinary Union attacks). Fairly or unfairly, many Democrats believe as Warren does: that Sanders should have done more to rein his fans in.

The perception that Sanders’s partisans are a fount of online nastiness and harassment is a real problem for Bernie. They make it harder to position himself as a potentially unifying leader at a time when his campaign needs to stop treating Democrats like the enemy.

So there are now two distinct debates about the Bernie Bro problem. First, there’s debate between the Sanders camp and more conventional Democrats over how much of a problem the dirtbag left is and how much blame Sanders deserves for their behavior. Second, there’s an emerging internal argument on the Sanders-friendly left over whether the dirtbag left is doing more harm than good.

Sanders’s 2016 and 2020 runs have helped revive the American left, helping take it from a sideshow to an influential part of Democratic party politics. The conclusion of the fights over Bernie Bros won’t determine the future of that movement on its own — but could end up having more influence than you might think.

The “Bernie Bro” is a stereotype — but the “dirtbag left” is real

The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer seems to have coined the term “Berniebro” (his spelling) in a 2015 article, a piece that was more an impressionistic, semi-serious sketch of a kind of person than an actual attempt to identify a political demographic. It described an obnoxious, if basically well-meaning, young, white, male Sanders supporter.

“The Berniebro is not every Bernie Sanders supporter. Sanders’s support skews young, but not particularly male. The Berniebro is male, though. Very male,” he wrote. “The Berniebro doesn’t really talk about how President Bernie Sanders would interact with the GOP-controlled House of Representatives. The Berniebro talks a lot about DC insiders, though.”

After Meyer’s article, the phrase separated out into the two-word format — Bernie Bro — and became a common term of abuse for Sanders supporters in 2016. The basic idea was that Sanders’s most serious fans tended to be white, male, and privileged; they weren’t willing to acknowledge political reality and the need for compromises in the way that Clinton’s more diverse base was. (There were also concerns about online harassment by Bernie fans, which we’ll circle back to in a moment.)

The problem with the demographic argument, as Meyer himself noted, is that Sanders’s fans were not disproportionately male — and they certainly don’t fit the “rich white man” stereotype conjured up by the Bernie Bro phrase. The stereotype was wrong in 2016 and has become even more wrong in 2020.

In the first few primaries this cycle, Sanders cleaned up with Latino voters and Asian voters. He has won outright with young women and young African-Americans, reflecting the fact that age — rather than race or gender — is the biggest determinant of Sanders versus Biden support. It’s simply false to call Sanders a candidate of privileged white men. Some of Sanders’s fans have even started calling themselves Bernie Bros (or “Bernard Brothers”) as a form of ironic reappropriation.

Despite the Bernie Bro stereotype’s obvious deficiency, the term hasn’t gone away. Here’s a Google Trends chart of search interest in “Bernie Bro” over the course of five years, showing that interest has really picked up recently in the 2020 race:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19773829/Screen_Shot_2020_03_06_at_4.29.31_PM.png) Google Trends

Google TrendsThis peak in interest has largely coincided with Sanders becoming first the frontrunner and then, shortly thereafter, the only serious remaining challenger to a surging Joe Biden. In January, the New York Times ran a lengthy piece on anger inside the Democratic Party over the behavior of those believed to back Sanders. A few examples:

Some progressive activists who declined to back Mr. Sanders have begun traveling with private security after incurring online harassment. Several well-known feminist writers said they had received death threats. A state party chairwoman changed her phone number. A Portland lawyer saw her business rating tumble on an online review site after tussling with Sanders supporters on Twitter.

More recent examples include the Nevada Culinary Union doxing and the flooding of Warren’s replies on social media with the snake emoji, referring to the idea that she’s a traitor to the left for claiming that Sanders once told her that a woman couldn’t win the presidency.

The Times reporters framed this as a kind of modus operandi, suggesting that this is a relatively common thing:

When Mr. Sanders’s supporters swarm someone online, they often find multiple access points to that person’s life, compiling what can amount to investigative dossiers. They will attack all public social media accounts, posting personal insults that might flow in by the hundreds. Some of the missives are direct threats of violence, which can be reported to Twitter or Facebook and taken down.

More commonly, there is a barrage of jabs and threats sometimes framed as jokes. If the target is a woman, and it often is, these insults can veer toward her physical appearance.

To be clear, there’s a difference between what’s described in the first paragraph and the second.

No one is defending doxing and threats of violence. The campaign has condemned this behavior in the strongest terms; it’s unclear who’s responsible for it and, in the absence of direct evidence, it’s unfair to hold the Sanders campaign or any of its prominent supporters responsible.

The insults described in the second paragraph, however, are the sort of thing that the dirtbag left valorizes. Its leading voices believe very deeply that biting mockery — including, yes, insults targeting your opponents’ physical appearance — are a vital tool for holding the powerful accountable. It’s not all that Chapo Trap House (for example) does; a lot of the show features conventional punditry and political analysis from a socialist point of view, leavened by a heavy dose of irony. But what makes their political style distinctive is its embrace of harsh, often cruel, humor as a deliberate political tactic.

“To dismiss vulgarity as a tool for fighting the powerful, to say that being mean is ‘ridiculous,’ is to deny history, and to obscure a long and noble tradition of malicious political japery. In fact, ‘being mean’ not only affords unique pleasures to the speaker or writer, but is a crucial rhetorical weapon of the politically excluded,” Chapo host Amber A’Lee Frost wrote in a 2016 essay titled “The Necessity of Political Vulgarity” in the left-wing magazine Current Affairs.

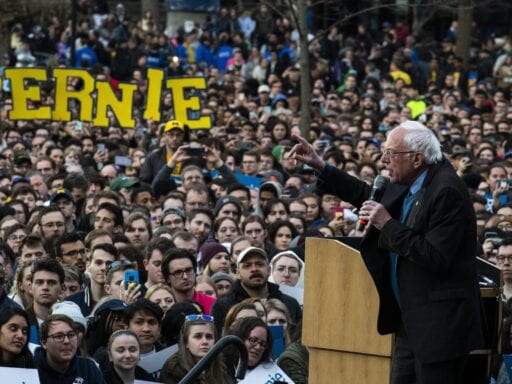

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19779515/1205529850.jpg.jpg) Brittany Greeson/Getty Images

Brittany Greeson/Getty Images“Real people are angry about the status quo and if that news is distressing to financially comfortable journalists who see the election only as an opportunity to harvest pageclicks then they deserve to be distressed,” Chapo-affiliated writer Alex Nichols argued in a now-deleted Medium essay.

The dirtbag left, which generally is defined to include Chapo and similar left podcasts Red Scare and Cumtown, practices what it preaches. In a single live taping in Iowa attended by the New York Times’s Nellie Bowles, Chapo hosts referred to Michael Bloomberg as a “midget gremlin,” Pete Buttigieg as a “bloodless asexual,” and Biden supporters as “gelatinous 100-year-olds.” They have encouraged flooding Warren’s social media mentions with snake emojis.

After the New Hampshire primary, pseudonymous Chapo co-host Virgil Texas tweeted a still from the movie Salo to mock Buttigieg’s campaign:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19776984/EQn8ipJX0AIJPUy.jpg)

A lot of observers were furious about the tweet’s homophobic overtones. While Virgil has deleted it, his co-host Will Menaker defended the thinking behind it:

Salo is about a group of bourgeois sadists and philistines who make a group of young people torture each other because they can. It reveals the libidinal, nihilistic pleasure that undergirds fascism, everyone mad at Virgil’s tweet about Salo reveals the exact same thing lol

— Will ♂️Menaker (@willmenaker) February 14, 2020

The dirtbag left cannot be as easily separated from the Sanders campaign as anonymous online harassers.

Sanders himself has sat down for an interview with Virgil; his speechwriter David Sirota and national press secretary Briahna Joy Gray have both been on the show. For the past few months, Chapo has done a kind of rolling pro-Bernie tour — selling out live shows in vital primary states prior to the contest and encouraging attendees to go out and work the campaign. The show is a financial powerhouse, raking in around $168,800 per month through Patreon subscriptions.

At least one (former) campaign staffer shares their ethos. The Daily Beast’s Scott Bixby reported that Ben Mora, a Sanders organizer in Iowa and Michigan, seems to have run a Twitter account called “Fags against Pete” that posted “scatological” tweets about the former South Bend mayor. Mora’s private account described Elizabeth Warren as, among other things, “an adult diaper fetishist.”

The Sanders campaign fired Mora after Bixby’s article came out. But Chapo defended him, with Virgil Texas describing him as “one of the best organizers I’ve ever met and a true exemplar of the posting-to-praxis pipeline.” After the article, Bixby faced backlash from Bernie fans; he was doxed and sent thousands of spam text messages.

Bernie’s dirtbag left problem

It’s true that all the candidates have nasty supporters; Sanders doesn’t have a monopoly on fans who have treated their opponents cruelly online.

But there’s no equivalent to Chapo and the other dirtbag left outlets on the other side of the Democratic Party’s internal divide — a closely allied media outlet that has elevated online abuse of its opponents into a political value. Fairly or not, the prominence of these Sanders supporters and their many social media supporters has shaped the way that media and Democratic Party elites think about the campaign — and maybe even affected some ordinary voters.

Roughly 22 percent of Americans use Twitter, a not-so-large percentage of the overall public. But virtually everyone in politics and media uses the platform, so the behavior of what are almost certainly a small fraction of Bernie fans on that platform has an outsized impact on the way that the American elite views Sanders. And that does matter for his campaign.

To understand how this works, it’s worth watching the entirety of Warren’s interview with Maddow on the subject. She starts off by talking about her long friendship with Sanders, how much respect she has for him. And then she pivots to an emotional discussion of online harassment; you can hear that it’s clearly shaped her perception of the race:

In the interview, it’s clear that Sanders’s disavowals of online harassment ring a little hollow in Warren’s ears. Given that the candidate and his staff have appeared on Chapo, you can understand her thinking. It might seem like Sanders is speaking out of both sides of his mouth: vaguely disavowing online anger in public statements while his campaign reaches out and appeals directly to the people purveying it.

The purported aim of all the pro-Sanders trolling, the snake emojis directed at Warren on Twitter, and the vitriolic attacks on the Nevada Culinary Union is to shame or bully the targets into getting behind Sanders. Judging by this interview, it seems to have had the opposite effect on Warren.

And what people like Warren think about this matters. If Democratic politicians see the Sanders campaign as a fount of negativity and anger, and a source of direct attacks on them and people they admire, they’re less likely to see it as something they’re comfortable lining up behind. And these sorts of endorsements can be significant in primaries; support from Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-SC) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) seems to have really helped buoy Joe Biden in their respective states.

Fundamentally, if Sanders and his movement want to succeed in remaking the Democratic Party in their image, they can’t just drive out every person in a position of power. To go from insurgents to party leaders, they need to figure out a way to persuade the rest of the party to join its cause. Right now, it seems like pro-Sanders online brigades are making that harder.

Some online Sanders supporters have dismissed this attitude as childish: that Warren and other progressives are letting their hurt feelings get in the way of their own political goals. What matters more, they ask rhetorically — your mentions or universal health care? Are you really concerned about mean comments, they ask, or just playing into a smear campaign led by moderates?

This response, in the mind of Sanders’s critics, is in some ways the problem. The dirtbag left sees the race in such starkly moral terms — either you support Bernie or you want poor people to get sick and die — that they’re willing to countenance abusive tactics in order to get people on board. They don’t understand how anyone could disagree with Sanders in good faith, or how treating someone viciously might be counterproductive to the cause they profess to care about.

The Sanders campaign did not respond to a request for comment on this story by publication time. But in the wake of Joe Biden’s Super Tuesday ascent at Sanders’s expanse, some of his supporters are starting to debate what went wrong — and that includes, to a limited degree, pointing the finger at the dirtbag left.

New York magazine’s Sarah Jones, a prominent writer on the socialist left, argued that there’s a germ of a point to the Chapo arguments; that the elite obsession with “civility” justified treating truly bad people in positions of power with undeserved respect. But this, she believes, has been taken too far — to justify outright, purposeless meanness.

“Some of you interpreted critiques of civility politics as though they justified performative cruelty,” she tweeted.

Patrick Iber, a historian and editorial board member at the left magazine Dissent, made related arguments at length on Twitter — noting that, in real life interactions with voters, the harassment issue keeps coming up again and again.

“I can’t tell you how many people I’ve talked about whose major concern about supporting Sanders isn’t Sanders himself but specific bad experiences they’ve had with supporters,” he writes. “We’ve reached the limits of how far the politics of being a jerk will take you. To go beyond that, we need to show that we can welcome allies.”

This backlash, both from mainstream Democrats and some on the pro-Sanders left, raises two questions.

First, does the dirtbag left have an interest in reforming — or are they even capable of it? And second, what concrete steps can the Sanders campaign take to repair its image?

It’s hardly the most cosmic issue at stake in the 2020 election. But it’s an increasingly important one politically, one that could influence just how much power Sanders and his allies wield in the Democratic Party in the coming years.

Author: Zack Beauchamp

Read More