Many voters simply don’t believe a politician could hold toxic policy stances on health care.

Prior to the passage of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, health insurance companies could (and routinely did) decline to offer coverage to patients with preexisting health conditions. This behavior is common sense from the standpoint of insurance underwriting — nobody is going to sell you a homeowners’ insurance policy if your house is already on fire — and the idea that it should be allowed is a straightforward aspect of free market thinking.

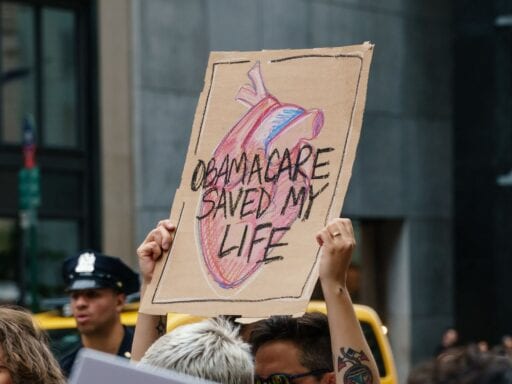

Congressional Democrats and President Barack Obama banned the practice. But Donald Trump and congressional Republicans tried to bring it back with their various ACA repeal efforts, and this has become one of Democrats’ most potent political attacks against Republicans. Not only did Republicans try to scrap these regulations back in 2017 and 2018, they are still trying to scrap them in the form of a lawsuit pending at the Supreme Court — even though Trump himself keeps lying and claiming he supports these protections.

Some people believe him. And according to Sarah Kliff and Margot Sanger-Katz of the New York Times, some of them believe him because they recognize that his real position is politically toxic:

“There is not a single guy or woman who would run for president that would make it so that pre-existing conditions wouldn’t be covered,” said Phil Bowman, a 59-year-old retiree in Linville, N.C. “Nobody would vote for him.”

Mr. Bowman cast his ballot for President Trump in 2016, and supports him in this election as well.

Bowman is, of course, mistaken. But the heuristic he’s using isn’t crazy. I don’t really know anything about Al Gross, the independent running to unseat Sen. Dan Sullivan in Alaska, but if someone told me that Gross wants to ban fossil fuel extraction I wouldn’t believe him. Why? Because even though there are plenty of Americans who do want to ban fossil fuel extraction, anyone running on that platform in Alaska would obviously lose, so there’s just no way he’s doing it.

But in Trump’s case, the inference is wrong. It’s true that his position on preexisting conditions is politically toxic. But it’s still his position. And there’s a long tradition of Republicans taking advantage of voter incredulity in this way.

The politics of incredulity

The Kliff/Sanger-Katz story reminded me of Robert Draper’s reporting from the 2012 cycle on the challenges that the then-new Priorities USA Super PAC faced in trying to develop effective ads to use against Sen. Mitt Romney.

One of their first ideas was to take note of the fact that Romney was advocating a bunch of unpopular ideas, and run ads highlighting that. It didn’t work, because the actual Romney policy mix — huge long-term cuts in Medicare in order to create budget headroom for large tax cuts for the rich — sounded so absurd (emphasis added):

Burton and his colleagues spent the early months of 2012 trying out the pitch that Romney was the most far-right presidential candidate since Barry Goldwater. It fell flat. The public did not view Romney as an extremist. For example, when Priorities informed a focus group that Romney supported the Ryan budget plan — and thus championed “ending Medicare as we know it” — while also advocating tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans, the respondents simply refused to believe any politician would do such a thing. What became clear was that voters had almost no sense of Obama’s opponent.

Since Romney’s defeat, Republicans have invested a lot of time and energy into being mad about the ways Democrats attacked his character.

I cover economic policy for a living, and have done so for 17 years now. So I know that a lot of smart, competent people who are kind and friendly in their interpersonal behavior sincerely believe that depriving working and middle-class families of economic resources to reduce taxation on the rich is the right thing to do. I am not sympathetic to that agenda, but a healthy number of decent people do think that way, and they are extremely influential in Republican Party politics.

But most voters find these ideas so outlandishly bad that they’ll only believe someone espouses them if you can convince them first that the person in question is a heartless monster. Priorities USA ultimately did, somewhat wrongly, convince people to think of Romney this way, and in doing so succeeded in driving home the larger (and completely accurate) point that these were his policy ideas.

Still, it’s continually a struggle. Consider what happened when congressional Republicans tried to respond to 9/11 with a capital gains tax cut (emphasis added):

The struggle really began less than 48 hours after the terrorist attack, when Bill Thomas, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, tried to ram through a sharp cut in the capital gains tax. Even opponents of the capital gains tax generally acknowledge that cutting it does little to stimulate the economy in the short run; furthermore, 80 percent of the benefits would go to the wealthiest 2 percent of taxpayers. So Mr. Thomas signaled, literally before the dust had settled, that he was determined to use terrorism as an excuse to pursue a radical right-wing agenda.

A month later the House narrowly passed a bill that even The Wall Street Journal admitted ‘’mainly padded corporate bottom lines.’’ It was so extreme that when political consultants tried to get reactions from voter focus groups, the voters refused to believe that they were describing the bill accurately. Mr. Bush, according to Ari Fleischer, was ‘’very pleased’’ with the bill.

The point is simply that the roots of this dynamic are deep, and Trump is only somewhat incidental to them.

On a policy level, the Republican Party is deeply committed to a profoundly unpopular world view that says that progressive taxation to support broad social programs is immoral (see former Bush administration economist Greg Mankiw’s thoughts on moral philosophy) and inimical to economic growth. But these ideas are very unpopular, so Republican Party politicians tend to obscure them with deceptive rhetoric and try to keep the focus of national politics on other topics.

Consequently, people who align with Republicans on broad values themes — whether opposition to abortion rights, love of guns, patriotism, or panic at the thought of a diversifying country — find it simply not credible that their champions are actually running on a politically toxic agenda that would clearly lose elections.

The case for normalization

This adds up to a powerful case for Trump’s opponents to try to “normalize” his presidency — to try to focus more media attention on the banal policy stakes in the election and less on the president’s bizarre personal behavior and scandals. Conservative writer Charles Fain Lehman coined the term “diminishing marginal offensiveness” to describe the phenomenon in which new outrageous conduct does nothing to further erode the standing of a president who has been unpopular from the beginning.

By contrast, Trump’s opposition to raising the minimum wage is even less popular than his overall rating. A solid 64 percent of the public says it favors higher taxes on the rich. And there’s overwhelming public support for stricter air pollution rules.

But the fact that the minimum wage, higher taxes for the wealthy, the stringency of clean air rules, and a dozen other “normal” policy issues are on the ballot is rarely a focus of media coverage. To the extent that voters hear about these issues, it tends to come from Democrats’ ads where, as we have seen, it is somewhat challenging to get voters to believe that anyone could seriously be running on GOP economics.

That’s why Sean McElwee of Data for Progress told me that an effective use of time as someone nervous about the future of the country is to “harass you and other journalists personally to get you to cover health care instead of whatever else is in the news.” In the real world, journalists cover all kinds of stories. But which topics get flood-the-zone style treatment largely depends on audience response.

My colleague Dylan Scott has written that if Trump gets his way on health care, 20 million Americans could lose insurance, and Joe Biden’s plan would extend coverage to 25 million people. If those kind of stories routinely went viral, campaign coverage would be more issues-focused, and more people would know that this really is what Trump and other Republicans believe.

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Matthew Yglesias

Read More