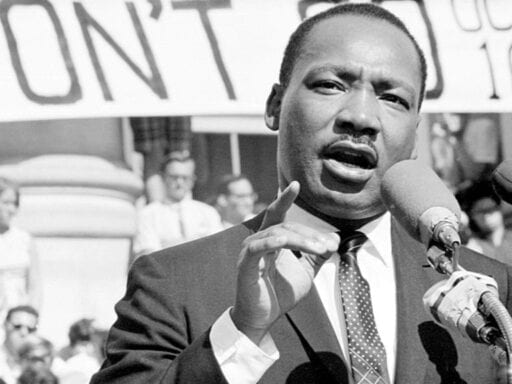

MLK was murdered more than 50 years ago. His legacy has been distorted ever since.

The following article was first published on April 4, 2018 on the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. In the decades since, his name has become synonymous with the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

But the King that America remembers (and uses to sell pickup trucks) and the man that actually lived are very different.

Jeanne Theoharis, a professor of political science at Brooklyn College-City University of New York, argues that the story of King’s activism has been watered down, obscuring his complexity and controversial aspects in favor of something far less complicated.

“There’s a desire to say, ‘We embrace Dr. King, we’re with Dr. King,’ and not really reckon with what he stood for,” Theoharis told me.

In her book A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History, Theoharis seeks to expand the conversation about King and the fight for civil rights in the US as a whole. She focuses on the people and histories that have been condensed or completely omitted, revealing a movement that is broader and far more complicated than the one students read about in textbooks.

I spoke with Theoharis about Martin Luther King’s legacy, Black Lives Matter, and why the fight against racial injustice is far from over, 50 years after his death.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

P.R. Lockhart

In your book, you speak of the “national fable” that has been built around the civil rights movement. What does that mean?

Jeanne Theoharis

When I talk about the national fable, it’s useful to think of President Ronald Reagan. Reagan comes into office in 1981 not supporting the idea of a holiday for Martin Luther King at all. But he came to see it as a way to signal his racial sensitivity.

In Reagan’s arguments for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we see what are going to become the key elements of the national fable.

The first is the focus on courageous individuals, not movements. The second is the idea that King and figures like Rosa Parks shone a light on injustice, and [said injustice] has since been eradicated. The third is the act of putting the movement and the problem of racism in the past. And the fourth is the idea of American exceptionalism — the belief that the civil rights movement demonstrates the power of American democracy.

So the Dr. King that we celebrate on the third Monday of January keeps getting smaller and smaller.

Another example is the King memorial in Washington, DC. Part of the memorial showcases quotes from King, and none of the quotes that were chosen include the words “segregation” or “racism.” It’s extraordinary — we have a monument to Dr. King that doesn’t speak to race.

We also don’t think about how many people opposed Dr. King when he was alive. That’s a much more uncomfortable history.

For example, most Americans did not support the March on Washington. In 1966, three-quarters of Americans did not agree with Martin Luther King. But because of the power of the movements that King was a part of, there’s a desire now across the political spectrum to say, “We embrace Dr. King, we’re with Dr. King,” and not really reckon with what he stood for.

P.R. Lockhart

You argue that this focus on individuals like King obscures how large the black freedom struggle is and how long the fight has been going on. Can you explain what you mean?

Jeanne Theoharis

Part of our fable of Dr. King has him doing everything, everywhere. There are many people in Montgomery, or Harlem, or Brooklyn, or Boston, or Los Angeles that were also doing things. When we learn about the civil rights movement, it seems like we have these exceptional individuals, they shine a light — and the problem is fixed. It makes work in the present seem less righteous, or feeble, because the things being highlighted now aren’t being fixed.

King and Rosa Parks are well known. But, what we actually know about them is a far cry from who they were and what they did.

We focus very heavily on the South, but King and others are adamant that racism is not a regional problem. Even in the early 1960s, King is traveling across the country to raise money for the Southern movement, but he’s also making speeches on the importance of housing desegregation, school desegregation, and police accountability, and reforms outside of the South.

P.R. Lockhart

While you were writing this book, what were some of the things you learned about King that people wouldn’t necessarily know?

Jeanne Theoharis

There’s this myth that King discovers the North after the Watts Uprising of 1965. And yet when you look at what King was doing from 1960 to 1965, it becomes clear how much he’s aware of, thinking about, and participating in [the fight for civil rights in] Northern cities.

He’s talking and thinking about issues that are very present for us today, like police brutality.

In one letter that King wrote two months after Watts, he talks about the horror and outrage against police brutality in the South, and the complete inattention and unconcern with police brutality in the North. That’s really interesting — it’s a King that speaks to our present, a King that is calling out Northern liberals and his Northern liberal allies for not working on the problems at home.

At the end of King’s life, he started talking about Vietnam and economics, and for some people, that’s when King becomes controversial; that’s when King becomes radical.

There’s a certain truth to that, but that narrative leaves out the fact that King was controversial much earlier.

P.R. Lockhart

Today, King is often framed as someone who just wanted black and white people to get along, rather than as a person who condemned white moderates who called his actions “untimely,” fought for economic justice, and critiqued the Vietnam War. What’s one idea of his that would make people uncomfortable?

Jeanne Theoharis

There are so many! Here’s one example. When the Movement for Black Lives linked the situation of black people in the United States to other international human rights issues, like the Palestinians, people were like, “Don’t say that, that’s inappropriate!” They said: “Be more like Martin Luther King!”

Are you kidding me? These are the exact same criticisms raised against him when he was alive.

There’s also this idea that we have Colin Kaepernick and the Black Lives Matter kids over here, and King in his hallowed chamber over there. For example, in 2014, Mike Huckabee wrote a blog post calling on Black Lives Matter to be more like Martin Luther King. (The post has been deleted, but Huckabee made similar comments in 2015.)

When he made that comment, I wrote an article saying a) they are being like King, and b) be careful what you wish for!

There’s this notion that King and the civil rights movement were embraced when things started in Montgomery. They weren’t. They were called un-American. King was constantly called a communist or a communist sympathizer.

In Montgomery, the NAACP helped on the legal side, but they actually kept some distance from the bus boycott at first because they weren’t sure about the tactics used.

There’s always been disagreements and different understandings of what appropriate protest looks like. And the fact that some of the criticism of Black Lives Matter comes from black leaders — it wasn’t all that different 50 to 60 years ago. The day after King spoke about the Vietnam War, the NAACP came out against him.

The disruptiveness of the movement has also been airbrushed. After the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile led to a standoff between police and protesters looking to march onto the highway in Atlanta, then-Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed said, “King would never take a freeway.”

Of course he did! They don’t look like freeways in Atlanta do now, but King wanted to stop business as usual.

P.R. Lockhart

In your book, you discuss how Coretta Scott King has largely been forgotten in discussions of the movement and King’s legacy.

Jeanne Theoharis

As we see more articles come out ahead of the anniversary, I’ve become increasingly dismayed that Coretta Scott King is seen as a side note.

Most people, if they have a sense of what Coretta Scott King did — it’s about protecting her husband’s legacy. And I think that misses the point. Coretta Scott King is a lifelong freedom fighter herself. She’s more political than King when they meet, she certainly influences his politics, particularly his growing internationalism and his stance on the Vietnam War. And then she continues, for decades after his death, [to fight for] issues that they had been committed to.

She takes the Poor People’s Campaign forward. She’s one of the people opposing the Vietnam War. The FBI surveilled Coretta Scott King for years after MLK’s death because they feared she was turning the civil rights movement into an antiwar movement. There’s something sobering about the fact that the FBI took her leadership more seriously than our historical memory has.

P.R. Lockhart

If we were to commemorate King in a way that takes all these overlooked aspects of his life and his activism into account, what would that look like?

Jeanne Theoharis

While King’s assassination is devastating, how we think about the assassination places the movement in the past. I’m hoping that this isn’t seen as just a ceremonial week, but a week of recommitment, of using the 50th anniversary of his death to sharpen our attention toward ongoing injustice in the United States.

Author: P.R. Lockhart

Read More