Tanner ’88 perfectly satirized the faux authenticity that candidates adopt to get elected.

One Good Thing is Vox’s recommendations feature. In each edition, find one more thing from the world of culture that we highly recommend.

At the 1988 Democratic National Convention, two candidates vied for the nomination: Jesse Jackson and Michael Dukakis. But if you seem to recall that there were actually three, you might have been watching Tanner ’88.

The HBO series had an all-star pedigree. Created and written by Doonesbury cartoonist Garry Trudeau, the show’s 11 episodes were directed by Robert Altman, who was in a critical slump at the time but had secured his place in film history a decade earlier with films like M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, Thieves Like Us, California Split, and Nashville.

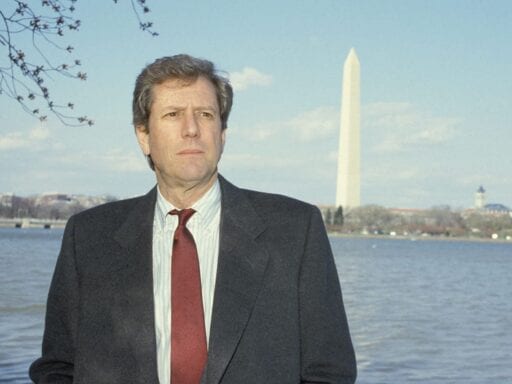

But the most interesting thing about Tanner ’88 wasn’t the creative team; it was the series’ whole concept. Tanner ’88 follows Jack Tanner (played by longtime Altman collaborator Michael Murphy), a liberal Democrat running a come-from-behind presidential race, as he and his staff travel the campaign trail from the New Hampshire primary in February to the Democratic National Convention in August. (The episodes were released on an irregular schedule, so that real-world events would sync up as much as possible to what was happening on the show.) Tanner’s college-aged daughter (played by a youthful Cynthia Nixon) joins the campaign, too, gently elbowing her father into more progressive causes like environmental issues and the abolishment of apartheid in South Africa.

The Tanner ’88 team set out to make the show with an unusual plan. They didn’t know what the plot would be, exactly, except that Tanner — who was not a real person running for president — would have to “lose” the nomination at the DNC in August of 1988. But everything else was pretty much up in the air. By the time the convention rolled around, there were only two candidates with a serious shot at securing the nomination — but in February, when production began, a host of contenders were still in the race: everyone from Jackson and eventual nominee Dukakis to Al Gore, Dick Gephardt, Paul Simon, Gary Hart, and Bruce Babbitt. (Joe Biden had dropped out under the fog of a plagiarism scandal, but he comes up in conversation several times nonetheless.)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21788211/tanner3.jpg) HBO

HBOAnything that happened over the course of the 1988 Democratic primaries was possible plot fodder. For instance, the name of Gary Hart — who dropped out of the race after a sex scandal in May 1987, only to reenter in December and then drop out again in March after a poor showing in the primaries — is invoked repeatedly on Tanner ’88, as a comparison point for Tanner’s far more wholesome scandal. (Tanner is divorced, and his girlfriend works for Dukakis; their relationship predated Tanner’s candidacy.) In the series’ fourth episode, which aired in May, Tanner’s staffers discuss whether they should send Hart flowers. There’s also a brief mention of the plagiarism scandal that prompted Biden’s dropout. Since the episodes aired irregularly and infrequently, especially in the spring, watching Tanner ’88 in real time would have been like seeing news coverage of developments in the Tanner campaign you’d missed over the past few weeks — except that they didn’t actually happen.

In contrast to other political comedies like the terrific Veep — which invented an entire alternate universe in which events from our own political world are rarely invoked — Tanner ’88 had made a deliberate choice to be about a candidate in this particular race, at this particular time in American history. The best way to do that, the creative team found, was to make sure their “candidate” and their cameras were nearby whenever and wherever the actual campaign was happening.

As a result, the first episode features a New Hampshire run-in with Pat Robertson, who was seeking the Republican nomination. In later episodes — especially the ones filmed after Tanner ’88 attracted attention and name recognition — several figures from the “real world” show up, including Babbitt, Hart, Jackson, Bob Dole, Ralph Nader, Chris Matthews, Gloria Steinem, Studs Terkel, Linda Ellerbee, and Kitty Dukakis, along with a bevy of advisers and strategists. Sometimes these people just make a cameo; other times they have dialogue and interact with Tanner, giving advice and talking about the race. They weren’t given a script, just a sense of the scenario, and sometimes not even that. For the most part, they knew they were appearing in a fictional series (though fleeting shots of figures like Tom Brokaw at the convention were likely an exception).

These folks were all politicians, so they knew what to do in front of cameras, especially these kinds of cameras. The crew was made up largely of people with TV news experience (including future Christopher Nolan cinematographer and Oscar winner Wally Pfister), and they used the same lightweight equipment that the actual TV news crews following candidates were using. Altman’s signature style, in which actors often deliver their lines all at once, talking over each other instead of taking turns speaking, made it feel like you were in a buzzing room full of busy people. The idea was to evoke the feeling of watching something newsworthy, even though viewers were in on the joke.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21788210/tanner4.jpg) HBO

HBOAnd that’s the grand irony of Tanner ’88. It’s a show about a candidate who rises to popularity because people see him as “authentic,” after one of his campaign staffers films him giving an impassioned speech to the team following a setback in New Hampshire. Tanner’s campaign slogan becomes “for real.” He is always polite, always kind, and seemingly genuinely interested in the people he talks to at campaign events, from high school students to mothers of young Black men shot in Detroit to celebrities at Hollywood fundraisers. He also speaks from the heart, making statements that strategists worry won’t test well, and gets arrested for activism. He needs coaching. He drinks beer. He’s in love. He’s a real guy.

But what the show chronicles is the high artifice that’s inherent to American political campaigns — not least at the national conventions, where the theatrics on the stage and in the arena (at least in the Before Times) take a back seat to the machinations and horse-trading going on in back rooms. Tanner ’88 is about the lack of reality in post-1960 politics, something that’s at least partly the fault of the cameras following Tanner and everyone else around. (The series bears some resemblance to Altman’s 1975 film Nashville in this regard.) People perform to the cameras and then worry about how what they did or said will play on the evening news. Characters are constantly watching TV coverage in the background. In one episode, a wedding is interrupted by a hovering helicopter trying to capture footage.

And so even Tanner — who disparages the Reagan White House as “intellectually inert, obsessed with TV” — is stage-managed by his staffers, who run focus groups and make deals and arrange the details behind the scenes so that they can shape the narrative that forms around him. It happens little by little over the course of the show, and Tanner knows it. He gripes to Babbitt — who’s dropped out of the race and wants to offer his advice to Tanner — that he feels as if he’s giving away a little more of himself every day, committing to things because his daughter has said on TV that he’ll do them, or agreeing to campaign ads that he privately finds kind of humiliating. Babbitt laughs, and they compare what kinds of makeup their respective staffers have told them to wear. To look better on camera, of course.

In scenes like this, we’re in on the joke. We’re witnessing a seemingly private conversation between Bruce Babbitt — a man who, when the series aired in 1988, had recently dropped out of the actual presidential race — and Tanner, who is really just an actor playing a guy named Jack Tanner. And we’re hearing them have conversations on camera. They’re aware they’re being filmed, and we know we’re watching something that’s been contrived for our entertainment. The implication is just below the surface: There’s not a lot of daylight between the “reality” of Tanner ’88 and the “reality” of what politicians and their campaign staff let us see on the news.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21788217/tanner1.jpg) HBO

HBOI was four years old when the 1988 convention happened, so beyond a hazy memory of the name Michael Dukakis, I don’t really remember any of it. But I started watching Tanner ’88 a few weeks ago as convention talk heated up. And I happened to be reading Joan Didion’s 2001 collection Political Fictions as well, in which the lead essay, “Inside Baseball,” is a piece of reporting from this same campaign.

So I let her eyes and ears be mine, and noticed that her observations about political campaigns and conventions lined up neatly with the point Trudeau and Altman were making with Tanner ’88. Didion writes about how campaigns on the road feel like movie sets, moving from location to location, and that the staffers act like a film crew: “There was the hierarchy of the set: there were actors, there were directors, there were script supervisors, there were grips,” she wrote. “There was the isolation of the set, and the arrogance, the contempt for outsiders.” She goes on to talk about how the campaign is viewed by journalists as “a big story” in which, in exchange for access, they “transmit the images their sources wish transmitted.” And she writes, with some exasperation, about how the images projected by campaign events are designed to generate a kind of credulous journalism. Reporters might cast those images as spontaneous — Michael Dukakis tossing a baseball on the tarmac outside his plane — but they’re often scripted moments intended to feed the candidate’s character, being created in real time.

The fact that Jack Tanner was a character being created in real time for entertainment purposes means that Tanner ’88 is not just richly entertaining; it’s terrific satire about the entire enterprise of American campaigns, particularly presidential ones. Elections have gotten far more intense in the decades since, thanks to increased polarization as well as an imperative to be thinking about the image you project at every single moment — especially if your job at a political convention is not just to give a speech and wheel and deal, but also to choose books and backdrops and camera angles for your Zoom.

In an interview recorded for the Criterion Collection’s release of Tanner ’88 in 2004, Robert Altman and Garry Trudeau talk about their memories of making the show. They speak of how they instructed the “real” politicians to act and talk since, Trudeau says, they’re nonactors, and you can’t give them a script and expect them to perform in scenes on cue.

“They’re nonactors,” Altman agrees. Then he stops himself and adds the line that gives away the game: “Well. Not that kind of actor.”

Tanner ’88 is available to stream on the Criterion Channel and on HBO Max. It’s also available to digitally rent or purchase on Amazon Prime. A four-part series, Tanner on Tanner, was released in 2004, but isn’t available on digital platforms. Political Fictions is available to purchase; the essay “Insider Baseball” is also collected in Didion’s book After Henry and in the New York Review of Books archives.

New goal: 25,000

In the spring, we launched a program asking readers for financial contributions to help keep Vox free for everyone, and last week, we set a goal of reaching 20,000 contributors. Well, you helped us blow past that. Today, we are extending that goal to 25,000. Millions turn to Vox each month to understand an increasingly chaotic world — from what is happening with the USPS to the coronavirus crisis to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work — and helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More