The triumph of “law and order” over the rule of law.

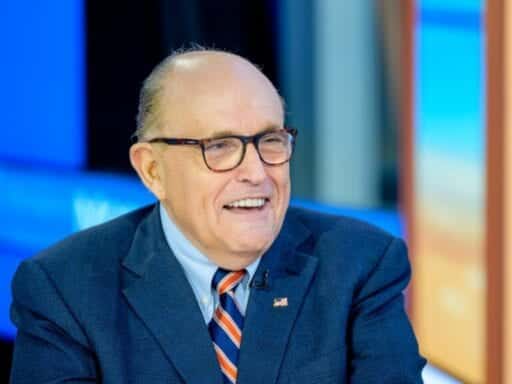

Like Michael Cohen before him, Rudy Giuliani, though described as Donald Trump’s “personal attorney,” does not appear to provide legal services in the conventional sense.

He is, rather, a television surrogate and all-around factotum who carries out requests on the president’s behalf while taking advantage of attorney-client privilege to put himself beyond the reach of subpoena power. And it appears he was the bag man for the Ukrainian caper that’s put Trump closer than ever to impeachment by the House of Representatives.

According to reporting by Greg Miller, Josh Dawsey, Paul Sonne, and Ellen Nakashima for the Washington Post, it was Giuliani who ran a “shadow Ukraine agenda.” The full scope of the agenda is still a matter of investigation, but it involves sidelining then-National Security Adviser John Bolton and other key officials to pressure the Ukrainian government into fabricating corruption charges against Joe Biden and his family.

Running sensitive diplomatic missions may sound like an odd job for an attorney not formally employed by the United States government. Adding that the attorney in question used to be mayor of New York City doesn’t really explain it.

But the happenstance that put Giuliani close to the scene of Ground Zero in Manhattan on 9/11 earned him a totally unwarranted reputation as an authority on national security matters. Early in the Trump era, he was actively pursuing a role as US secretary of state. The fact that he was totally unqualified seems to have hurt his cause in that regard. As did, according to reporting at the time from Dawsey and Shane Goldmacher, a desire to avoid public scrutiny of his “paid work for foreign governments.”

But Giuliani’s tendency to get mixed up in shady international dealings made him a perfect choice for the bag man role. And while nothing about his tenure as mayor suggests an abiding interest in Ukrainian security issues, during that period he did pioneer a style of politics that is recognizably Trumpy — featuring an extremely high ratio of spectacle and cultural grievance to interest in policy specifics, and a strand of authoritarianism that elevates law and order over the rule of law.

Rudy’s rise to power

Giuliani became famous as President Ronald Reagan’s appointee to serve as US attorney for the Southern District of New York. He prosecuted mob bosses and financial industry figures from the “Wolf of Wall Street” era and pioneered the use of the media-friendly “perp walk” to gain attention for his exploits.

Even at the time, careful observers questioned whether his reputation was built more on real accomplishment or flam-flam. William Glaberson reported for the New York Times that “five months after Mr. Giuliani left the office, some of those who are best qualified to judge him say in interviews that not all of Mr. Giuliani’s accomplishments were as impressive as his press clippings suggested and that his successes stemmed partly from extensive work by others and a healthy dose of luck.” Many of his biggest wins largely involved taking credit for the work of others (the Securities and Exchange Commission, the State Organized Crime Task Force), and some of his biggest prosecutions fell apart.

Nonetheless, he emerged from the 1980s as a well-known New York City Republican with a law-and-order reputation.

And in 1989, he got a big chance to run for mayor; the city’s incumbent white moderate Democrat Ed Koch was defeated in a primary by David Dinkins, a more liberal African American. Dinkins narrowly defeated Giuliani, but Rudy essentially kept on running for four years straight, fomenting a radicalized backlash against the city’s first black mayor.

A signature issue during that period was the new mayor’s efforts to create a civilian complaint review board that would oversee allegations of misconduct against NYPD officers. As Nat and Nick Hentoff recounted in 2016, Giuliani helped lead a police riot against the proposed reforms:

As many as 10,000 demonstrators blocked traffic in downtown Manhattan on Sept. 16, 1992. Reporters and innocent bystanders were violently assaulted by the mob as thousands of dollars in private property was destroyed in multiple acts of vandalism. The protesters stormed up the steps of City Hall, occupying the building. They then streamed onto the Brooklyn Bridge, where they blocked traffic in both directions, jumping on the cars of trapped, terrified motorists. Many of the protestors were carrying guns and openly drinking alcohol.

Yet the uniformed police present did little to stop them. Why? Because the rioters were nearly all white, off-duty NYPD officers. They were participating in a Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association demonstration against Mayor David Dinkins’ call for a Civilian Complaint Review Board and his creation earlier that year of the Mollen Commission, formed to investigate widespread allegations of misconduct within the NYPD.

In the center of the mayhem, standing on top of a car while cursing Mayor Dinkins through a bullhorn, was mayoral candidate Rudy Giuliani.

”Beer cans and broken beer bottles littered the streets as Mr. Giuliani led the crowd in chants,” The New York Times reported.

Witnesses, including New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin, reported racial invective from the crowd, which challenged Breslin with questions like, “Now you got a ni**er right inside City Hall. How do you like that?”

About a year later, New York had a new mayor — Rudy Giuliani.

Governing the ungovernable city

New York City today is safe for many, and difficult to afford, with a politics overwhelmingly dominated by the reality that lots of people want to live there. Strong demand for living in New York generates political conflict around gentrification, rent prices, infrastructure capacity, school zoning details, NIMBYism, developers, and resentment of the rich.

But when I was a kid in New York in the 1980s, it was a city that was widely seen — like essentially all other Northeastern and Midwestern cities — as in decline.

Population had fitfully fallen since the rise of postwar suburban development, crime was high, and while the city certainly had its expensive neighborhoods it was not by any means particularly difficult to afford a place to live that had a reasonably convenient commute to somewhere.

The city was widely regarded as “ungovernable” — paralyzed between intractable interest group demands and limited fiscal capacity. And while Giuliani’s demagogic approach won him the election, it was a tenuous victory. Dinkins carried Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, while Giuliani dominated heavily white areas of Queens and depended for his margin of victory on a thumping performance in Staten Island — a place with a very suburban vibe that voted the very same day in favor of a referendum to secede from New York.

Just four years later, Giuliani won a landslide reelection and was widely regarded as a success story. Crime was down, property values were up, and shows like Friends and Seinfeld (along with many of the less-fondly-remembered sitcoms from the Must See TV block like Caroline in the City) portrayed New York as a desirable place for young people to live.

Looking back in retrospect at the miraculous New York City turnaround, what’s striking is how little there really was to it. It was David Gunn’s six-year run as the head of the New York City Transit Authority from 1984 to 1990 that cured the subway of its graffiti problem and restored reliability to service. The city’s population, similar, had already started growing again by 1990. And crime, Giuliani’s signature issue, began to fall before he took office.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19231236/NYC_murders2.png) RobMagin1

RobMagin1What’s more, we know now that murder rates started to fall in virtually all major American cities in the 1990s. In retrospect, some analysts credit the natural waning of the 1980s crack epidemic and the delayed benefits of the switch to unleaded gasoline. A Clinton administration initiative to fund hiring of more police officers also seems to have helped.

It’s true that New York’s crime drop was unusually large, so there’s a decent argument that NYC-specific innovations around police tactics — specifically using COMPSTAT computer data to keep better track of exactly where crimes were happening — played a role.

But broadly speaking, it’s easy to tell a story in which Dinkins narrowly wins reelection in 1993 and then presides over four years of accelerating crime decline and leaves office term-limited, beloved, and well-positioned to challenge Al D’Amato in the 1998 New York Senate race. In this alternate reality, Giuliani becomes an obscure figure, Chuck Schumer rather than Hillary Clinton likely runs for Senate in 2000, and all the rest of American history plays out differently.

Instead, Giuliani won. And he aggressively sought — and received — the credit for the crime decline through both relentless PR efforts but also constant championing of the police in even their darkest hours.

Giuliani Time

Like Trump, Giuliani appeared to be deliberately courting accusations of racism as a way to position himself as the true champion of the city’s white majority.

In 1994 when veteran Rep. Charlie Rangel called on the mayor to do more outreach to black elected officials, Giuliani retorted that “they’re going to have to learn how to discipline themselves in the way in which they speak also.” That in turn prompted a scolding from Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and helped entrench perceptions in liberal intellectual circles (like my parents and most of their friends) that Giuliani was a racist, and perceptions in working class white circles that Giuliani was the victim of political correctness.

Early in his term, officers charged aggressively into a Harlem mosque based on a fake 9-11 call setting off a brawl that led to the injury of eight officers. Giuliani quickly positioned himself as the anti-Dinkins, insisting their was nothing wrong with the police officers’ response, even though they’d clearly failed to follow departmental guidelines about dealing with places of worship, and insisted “the only real issue was the assault on police officers.” Days later, the unarmed 17-year-old son of a prominent Brooklyn imam was shot after an arrest on drug possession charges, and Giuliani again simply backed the protesters.

Later, in 1997, Abner Louima was physically and sexually assaulted by police officers who subsequently tried to cover up the attack.

Louima initially told the press that the officers, while assaulting him, had said “it’s Giuliani time” — a claim that quickly became a focal point for liberal contentions that Giuliani’s pro-cop identity politics was encouraging misconduct. As the case moved to trial, however, Louima withdrew the claim, thus turning the incident into more grist for the grievance mill, as Giuliani said his critics owed him an apology.

The key policy dispute, however, continued to be about civilian oversight of the police department. To critics, the Louima case showed that police misconduct is a real problem that required a systematic policy solution, while to Giuliani it showed that the system worked, the police were in no need of oversight, and his critics were hysterical.

Crucially, the very existence of constant police-related controversies served to bolster the claim that something about Giuliani and his criminal justice policy was a very big deal. In retrospect, this seems false. Crime fell under the previous mayor and fell under Giuliani’s two successors, and it fell in virtually every other major city as well, making it unlikely that anything special was happening at all.

But at the time, the New York situation felt very special because Giuliani was such a touchstone in the debate over police violence. The 1999 Agnostic Front hardcore song “Police State” contains the line “Giuliani, Giuliani, Giuliani, fuck you die.”

After Amadou Diallo was shot 41 times by police officers who mistakenly thought he was reaching for a gun they were acquitted on criminal charges. Bruce Springsteen wrote a song about it titled “American Skin (41 Shots).” That earned him condemnation from Giuliani, who complained, “There are still people trying to create the impression that the police officers are guilty.”

The ultimate case of law and order versus the rule of law, however, came after the shooting of 26-year-old Patrick Dorismond who was shot in a scuffle with undercover police officers who appeared to be attempting to get him to sell them drugs (he was not a drug dealer). Giuliani responded to the shooting by releasing elements of Dorismond’s sealed juvenile record.

This had no relevance to the incident, since it had happened nearly 10 years in the past, but Giuliani explained to Fox News Sunday: “People do act in conformity very often with their prior behavior” and he “would not want a picture presented of an altar boy, when in fact, maybe it isn’t an altar boy, it’s some other situation that may justify, more closely, what the police officer did.’’

Dorismond, it turns out, had literally been an altar boy in Catholic school.

9/11 made him America’s mayor

Giuliani flirted heavily with running for Senate in 2000 but backed down amid some messy personal issues and the realization that he would likely lose.

With his term expiring in 2001 and an incumbent Republican governor set to run for reelection in 2002, Giuliani had no obvious path forward in national politics. What’s more, while he wasn’t exactly unpopular by the end of his term, it’s fair to say that the city was experiencing a fair amount of Rudy fatigue. Mark Green, a Manhattan liberal of the sort Giuliani had long defined himself against, was ahead in the polls and seemed likely to defeat Michael Bloomberg, who himself had stayed fairly aloof from Giuliani.

Giuliani had at this time been making headlines by picking weird fights about art with the Brooklyn Museum and seemed to have largely exhausted his policy agenda. People wanted some effort at mending fences between police and the black community, but Giuliani wasn’t going to touch that topic. And he seemed to have relatively little interest in education, transportation, and the other main elements of municipal government.

Then came the September 11 terrorist attacks, a confusing and frightening time for virtually everyone, and a perfect backdrop for Giuliani’s showmanship. Giuliani did not particularly do anything noteworthy on the day in question, and in retrospect his administration’s earlier decision to house the city’s emergency command center at 7 World Trade Center (which was destroyed in the attack) was a tragic error. But he offered a kind of commanding on-the-ground presence, and his leadership was reassuring to many moderate New Yorkers who’d voted for him but never in a million years would have backed George W. Bush for president.

Frightening, traumatic events tend to boost authoritarian aspects of people’s political psychology so the prevailing climate of that autumn gave a huge boost to Giuliani’s public standing. Giuliani himself attempted to leverage that boost into getting the state legislature to cancel the upcoming election and extend his term, which they did not do. But his surging popularity and strident public endorsement did help put Bloomberg over the top, contrary to the summer polling trends.

It also earned him a slightly baffling selection as Time’s Person of the Year and launched his second act in American politics.

Rudy Giuliani, anti-terrorism superstar

As the mayor of a heavily Democratic city, Giuliani had never been much of an orthodox Republican on policy.

He branded himself as solidly pro-choice, embraced LGBT rights at a time when Republican senators were refusing to confirm an openly gay ambassador, and was a pioneer of the “sanctuary cities” concept fighting to defend New York’s undocumented residents against Clinton-era immigration crackdowns (notably at the time, New York’s Latino population was predominantly non-immigrant Puerto Ricans and its undocumented population was tilted toward Eastern Europeans whites).

What’s more, back in 1994 Giuliani had endorsed Democrat Mario Cuomo’s reelection bid on the grounds that the Democrat’s budget ideas were better for the city than those of his GOP opponent. That could have ended up being a very savvy political move, except Cuomo lost the race which ended up landing him awkwardly on the shit list of a new governor of the same party.

But his performance on 9/11 and the weird anti-terrorism politics of the Bush years turned Giuliani briefly into a mainstream conservative icon. He delivered one of the featured speeches at the 2004 Republican National Convention and it was entirely about foreign policy and national security issues, with nothing to say about any topic a mayor would actually deal or know anything about. He launched a consulting business with his last pick for NYPD commissioner, Bernard Kerik, and tried to push Bush to appoint Kerik as Secretary of Homeland Security, an effort that was later derailed by revelations that Kerik had broken all kinds of laws. Even so, Giuliani entered the 2008 GOP primary and jumped out to a big early lead in the polls before collapsing under scrutiny.

Much of this was policy scrutiny — Giuliani was unacceptable to the Religious Right — but it also turned out that as mayor he’d billed city agencies tens of thousands of dollars to take trips to the Hamptons to carry on an affair with Judith Nathan. There were also many questions about his murky lobbying ties to foreign clients, including some deemed national security threats by the Bush administration. After the disastrous collapse of his presidential campaign, Giuliani seemed set to slip into obscurity (he was retirement age anyway) but then along came Trump.

Trump’s loyal foot soldier

It’s easy to forget now, but back in the fall of 2016 not only was Trump widely forecast to lose the election he’d been semi-disavowed by much of his party.

House Speaker Paul Ryan had formally stated that he would no longer campaign with or defend Trump, upwards of a dozen GOP senators pointed refused to endorse him against Hillary Clinton, and Ted Cruz delivered a memorable GOP convention speech in which he exhorted the crowd to “vote your conscience.”

This created an extremely valuable role for Giuliani in the Trump campaign. For starters, Rudy was a well-known public figure and a real Republican Party politician who had held elective office and been a featured speaker at GOP conventions. The specific details of the cloud of corruption and scandal under which he’d slinked away from public life had largely been forgotten, and while movement conservatives had been very alarmed by the idea of Giuliani as president they were happy to see him as a surrogate.

What’s more, unlike most GOP politicians, Trump was personally comfortable with Giuliani.

A notable feature of the Trump administration has been that Trump himself sometimes seems to get along better on an interpersonal level with big-city Democrats — at least older white ones like Schumer and Nancy Pelosi — than he does with churchy rural Republicans. Giuliani, like Trump, is in the very small Venn diagram of big-city Republicans, so they had a strong personal rapport.

Giuliani also more or less shares Trump’s distinctive shamelessness. He once got in a screaming fight about ferrets while hosting a call-in radio show. And Giuliani, like Trump, doesn’t seem to really care about public policy as it’s conventionally understood. Michael Bloomberg had a controversial education policy agenda and Bill de Blasio has a different controversial education policy agenda.

Bloomberg also revamped aspects of New York’s transportation, and de Blasio has made fitful efforts to change housing policy. It would be an overstatement to say that Giuliani didn’t do anything on these subjects, but he didn’t engage with them. The only signature Giuliani policy was opposing civilian oversight of the NYPD. But even there the point was less any specific policy content than a kind of culture war about the police. He liked to fight with people who complained about police brutality more than he liked to delve into the details of crime control policy.

When it was politically important for him to be pro-choice and pro-LGBT he was, then he seemed surprised that the religious right had a problem with those positions, and now that he’s on Team Trump he doesn’t care about them at all — nor does he seem to remember that he used be a strident critic of strict immigration enforcement. During his flirtation with being a foreign policy expert, Giuliani was a pretty hard-core neoconservative hawk, something he also gave up to join the Trump Train.

Rather than having policy views in common with Trump, the two men share a common lack of real interest in policy views. They have, instead, strong views about who should be in charge (men with guns and badges acting in alliance with sympathetic businessmen) and who should shut up (everyone who has a problem with that).

And for all their law and order posturing, they share a distinct record of total contempt for actual laws and legal procedures. The point of law and order politics isn’t that you don’t stage a riot or leak a sealed juvenile record or make sure your police commissioner isn’t corrupt — it’s to make sure the law and order people stay in charge.

While Giuliani’s mission to Kyiv may not have been ethical, in accordance with the law, or reflective of how American foreign policy is supposed to operate it was absolutely in pursuit of keeping the law and order people in charge of the government.

That, for Rudy, has always been good enough.

Author: Matthew Yglesias

Read More