Just when Trump thought he was out of the Mueller investigation, they pull him back in.

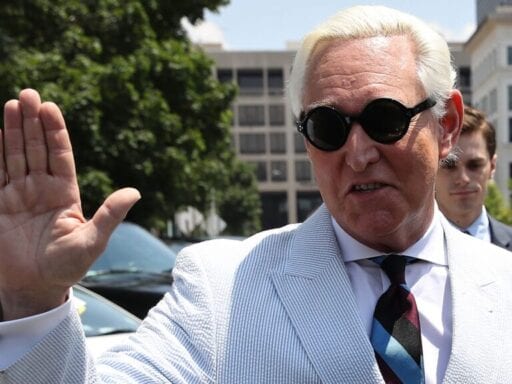

While Donald Trump is attempting to avoid Richard Nixon’s presidential fate, the Trump adviser with Nixon’s face tattooed on his back is going on trial.

The trial of Roger Stone — the longtime GOP operative and dirty trickster who was indicted by special counsel Robert Mueller — will finally kick off in Washington, DC, this Tuesday.

And the proceedings will feature ample discussion of Donald Trump and advisers such as Paul Manafort and Steve Bannon, with a focus on just what, exactly, Stone was telling them about those hacked Democratic emails back in 2016.

The charges against Stone allege that he tried to obstruct the House Intelligence Committee’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election by lying to the committee about his efforts to contact WikiLeaks and by encouraging another witness to lie for him as well.

Russian intelligence officers’ hacking of leading Democrats’ emails was one of the key planks of the Kremlin’s effort to interfere with the 2016 campaign. Those emails, from the DNC and Hillary Clinton’s campaign chair, were eventually posted publicly by WikiLeaks. But one big question Mueller explored was whether any Trump associates were involved in the dissemination of those hacked emails.

That investigation eventually focused on Stone, who had both publicly and privately claimed some advance knowledge about what WikiLeaks was planning. Prosecutors claim senior Trump campaign officials “directed” Stone “to inquire” about future WikiLeaks releases, and have revealed emails showing that Stone indeed tried to get in touch with the groups.

But what, exactly, prosecutors believe truly happened between Stone and WikiLeaks isn’t clear. They didn’t end up charging Stone about anything he actually did in 2016, but rather his alleged attempts to lie about and cover up what happened afterward. And the Mueller report’s final word on what, if anything, Trump’s advisers knew about WikiLeaks’s plans was redacted — to avoid prejudicing this very trial.

The proceeding is certain to be a sensation. Steve Bannon, the former top White House adviser, is reportedly likely to testify — against Stone. Prosecutors have signaled they will discuss several phone numbers for Trump himself, apparently to allege Stone spoke with the president about Wikileaks. Stone, a colorful character, may take the stand in his own defense. And all of this will unfold at a perilous moment for Trump, with unpredictable effects on the House’s impeachment inquiry.

Who is Roger Stone?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19337776/GettyImages_853851716.jpg) TNS via Getty Images

TNS via Getty ImagesStone has had a reputation for political shenanigans since he was a 19-year-old volunteer carrying out dirty tricks to embarrass Richard Nixon’s 1972 Republican primary opponent — something that earned Stone a minor role in the Watergate hearings.

As a Republican campaign operative, he worked for Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bob Dole; as a highly paid lobbyist, he worked alongside his friend Paul Manafort for a host of seedy clients. And he’s long been known as a colorful character who rejoices in the dark side of politics: scandals, smears, division, and negativity. Journalists have called him “the state of the art Washington sleazeball” and the “boastful black prince of Republican sleaze.”

Stone also, incredibly enough, spent nearly three decades trying to get Donald Trump for president before Trump actually went through with it. The two met in the mid-1980s, as Trump hired Stone and Manafort’s firm to do lobbying and PR for him. After Trump released his book The Art of the Deal in 1987, Stone urged him to consider running for president the following year, but Trump demurred. In 1999, Stone ran a presidential exploratory committee for Trump — but Trump again ended up not officially running.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19338246/AP_18121718774455.jpg) Daniel Hulshizer/AP

Daniel Hulshizer/APThe two had their ups and downs over the years (“Roger is a stone-cold loser,” Trump told the New Yorker in 2008, arguing he “always tries taking credit for things he never did”). But by 2011, as Trump mused about challenging President Barack Obama, Stone was egging him on again, urging him to spread conspiracy theories about Obama’s birthplace.

So when Trump finally did launch his presidential campaign in June 2015, Stone was on board as an official campaign adviser. But he didn’t last long. After clashing with then-campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, he left his official role in August 2015.

Yet Stone remained in contact with Trump himself to some extent and continued to try to support Trump’s candidacy from the outside. And some of those outside efforts landed him at the center of the Mueller investigation, leading to his arrest and indictment this January.

Why was Roger Stone indicted?

The charges allege that Stone attempted to obstruct the House Intelligence Committee’s investigation into Russian interference in 2017 because he wanted to hide the truth about what happened between him and WikiLeaks during the 2016 campaign.

WikiLeaks infamously posted thousands of emails that Russian intelligence officers had hacked from the DNC (in July 2016) and Clinton campaign chair John Podesta (in October 2016), rocking the presidential campaign.

In the midst of all this, Stone was telling top Trump officials that he had some inside knowledge about what WikiLeaks and the group’s founder Julian Assange were planning next, prosecutors allege. And he was telling one of his associates — conservative author Jerome Corsi — to try and find out more about what Assange had.

“Get to Assange” at the “Ecuadorian Embassy in London and get the pending WL emails,” Stone emailed Corsi on July 25, 2016. Corsi’s response to Stone, sent about a week later, contains a curious reference to “Podesta” — even though it was not yet publicly known that Podesta’s emails had been hacked.

Stone then began publicly making ominous predictions about what WikiLeaks was planning. He claimed he’d had “some back-channel communication” with WikiLeaks and Assange. He tweeted in August that it will soon be “Podesta’s time in the barrel.” And in the days before the Podesta emails were actually posted by WikiLeaks, Stone exchanged emails and messages with Trump campaign CEO Steve Bannon and Bannon’s associates about WikiLeaks’s plans.

Enough of this occurred in public that Stone earned a good deal of scrutiny. Congressional investigators probing Russian interference in the 2016 campaign wanted to know if Stone did in fact have inside information about the stolen emails, who he might have gotten that information from, and whether he told anyone in the official Trump campaign.

So prosecutors allege that, when the House Intelligence Committee started asking questions in 2017, Stone lied. Specifically, Stone falsely claimed all of his information about WikiLeaks’s plans came from a single “intermediary”: radio host Randy Credico. He also claimed he never asked his intermediary to communicate anything to Assange, said he had no relevant documents to hand over to the committee, and pressured Credico into backing up his false cover story.

For all that, Mueller’s team charged Stone with one count of obstructing an official proceeding, five counts of making false statements, and one count of witness tampering.

What actually happened here?

What did Stone actually know about WikiLeaks? Who did he learn it from? And did he share inside information about this with the Trump campaign?

Those questions have never fully been answered by the government. Mueller’s prosecutors had enough information to feel comfortable charging Stone for lying, but they haven’t publicly laid out any larger explanation about what they feel the truth was.

Such an explanation, however, may be sitting in the Mueller report, covered by black bars.

Recall that Mueller did not end up filing any criminal charges against Trump associates related to the hacking and leaking of emails. The investigation, he said, did not “establish” such a criminal conspiracy.

That is different from claiming Trump associates had no involvement in the email leaks. In fact, there is a section of the report titled “Trump Campaign and the Dissemination of Hacked Materials.” It’s 10 pages long, and the only public version of it is heavily redacted. Here are a few tastes.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19339077/Screen_Shot_2019_11_01_at_2.27.04_PM.png)

Most of the redactions in this section were made under the justification that they’d cause “Harm” to an “Ongoing Matter” — and, from context, it’s clear that that ongoing matter is Roger Stone’s prosecution. (Court rules require that the government not release derogatory information about a defendant before the trial.)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19339084/Screen_Shot_2019_11_01_at_2.27.32_PM.png)

You can see above that the redacted material in this section involves Trump personally. “Shortly after the call candidate Trump told [deputy campaign manager Rick] Gates that more releases of damaging information would be coming,” one unredacted bit reads. It’s likely that Roger Stone was at the other end of that call, but those frustrating redactions prevent us from seeing the full story.

Much of this section discusses Corsi, who Stone had told to “get to Assange.” But again, it’s mostly redacted.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19339094/Screen_Shot_2019_11_01_at_2.29.32_PM.png)

It is likely that prosecutors trying to make their case at Stone’s trial will reveal at least some of what is under these redactions. If, for whatever reason they don’t, this material could be released after Stone’s trial ends. So we do seem to be getting close to learning more about one of the Mueller report’s biggest missing pieces.

What else should we expect to see at Roger Stone’s trial?

For one, expect there to be some interesting witnesses. One will likely be Rick Gates, the deputy Trump campaign chair who flipped on his longtime boss Paul Manafort last year, testifying against him at his own trial.

Steve Bannon, the former Trump campaign CEO and White House chief strategist, is also reportedly likely to appear as a government witness against Stone. Bannon seems to have told the government about discussions he and Stone had about WikiLeaks. Because of that, Stone has publicly attacked Bannon, calling him a “#muellerinformant”.

Trump himself will also be the subject of ample discussion. One of the false statements charges against Stone focuses on his claim that he never discussed his WikiLeaks intermediary with anyone involved in the Trump campaign. To prove Stone was lying here, prosecutors have signaled they intend to bring up various phone numbers — for Trump, Bannon, Gates, Manafort, and others — that will make clear Stone was in contact with them at key moments.

And then there’s the question of whether Stone will testify in his own defense (something Manafort did not do). Earlier this year, Stone’s attorney Bruce Rogow asserted to the New Yorker that “Roger will definitely take the stand in his own defense” and that “it will be key to the case.” Such a move is often not advisable for a defendant, but Stone has a good deal of confidence in his talents at obfuscation. The trickster may have one more trick to play — though the audience, a Washington, DC, jury, may be a skeptical one.

Author: Andrew Prokop

Read More