The “median” justice tells us a lot about the Supreme Court, including how much it needs to be fixed.

Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy — who announced his retirement last week — was often called one of the most powerful people in America.

He was a Reagan appointee and generally on the right, but he did break from the Court’s conservatives on some key issues. For decades, he occupied a middle position on the Court, with four of his colleagues on either side of him — a position scholars have dubbed the “median justice.”

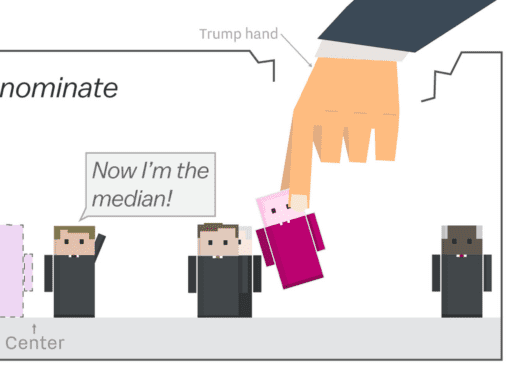

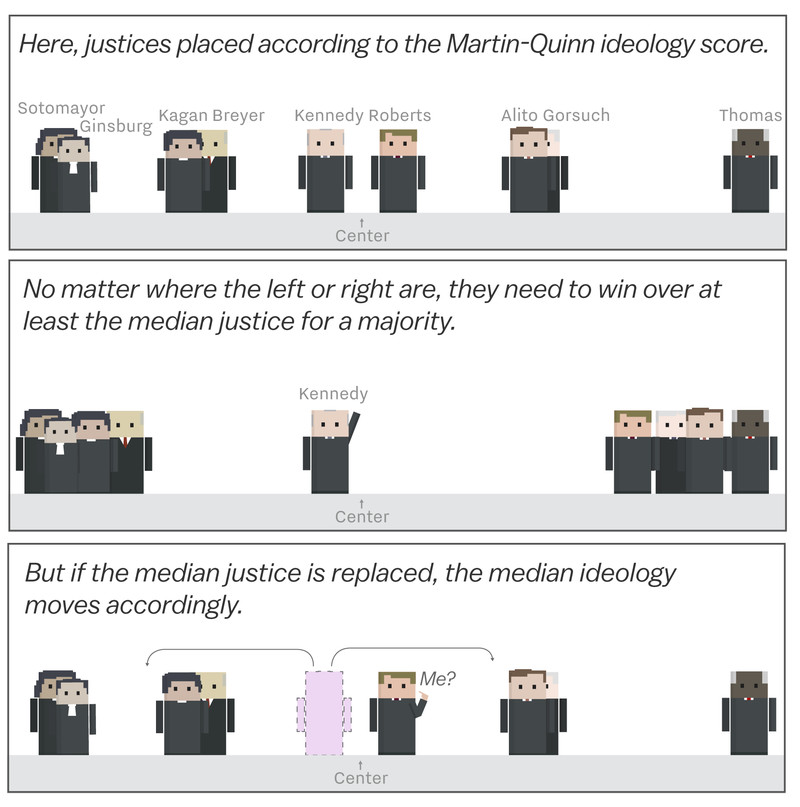

The way to think about the median justice is simple: Justices on the extremes can be very liberal or conservative, but each side must win at least five votes — which makes the median justice potentially very powerful.

If the Senate confirms President Trump’s nominee to replace Kennedy, the court’s median justice will almost certainly be more conservative.

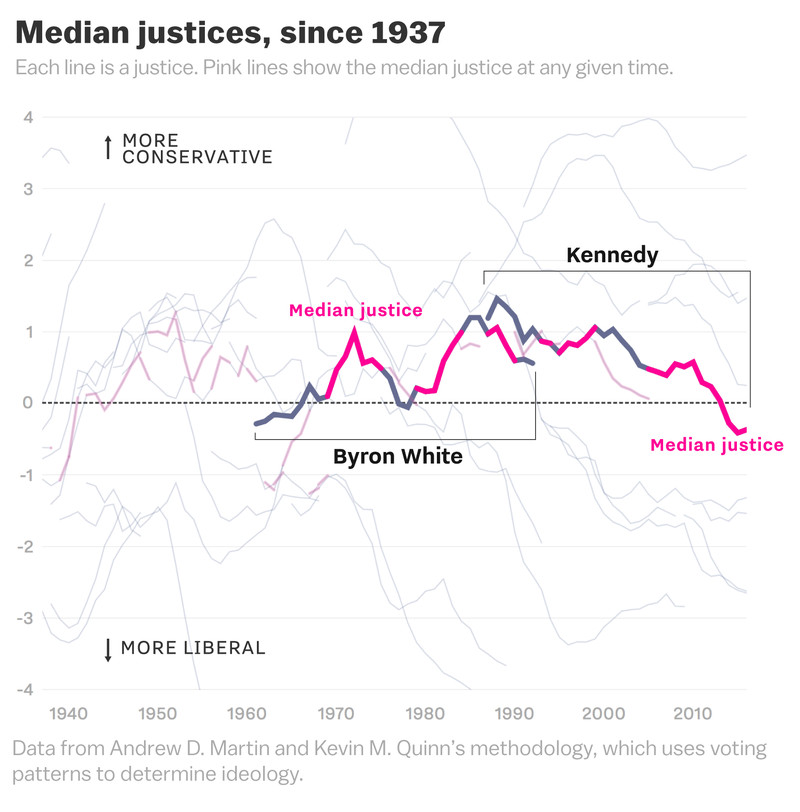

Using a measure developed by political scientists Andrew Martin and Kevin Quinn, the most likely scenario is that Chief Justice John Roberts will be the next “median justice,” assuming Trump’s nominee is more conservative than Roberts. (In the unlikely scenario the nominee is more moderate, the newest justice would become the median.)

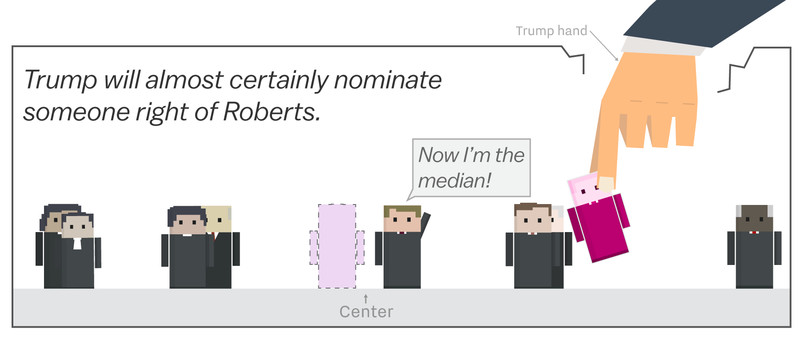

The Martin-Quinn ideological score shows us that Roberts has actually been moving to the center since his appointment, much like Kennedy did over his career — a reminder that the median justice may not be ideologically static over the course of their Supreme Court stint.

Could Roberts continue that drift to the middle? Maybe. But given Roberts’s record, his slow shift to the center probably won’t assuage people who are worried about specific issues, like reproductive rights.

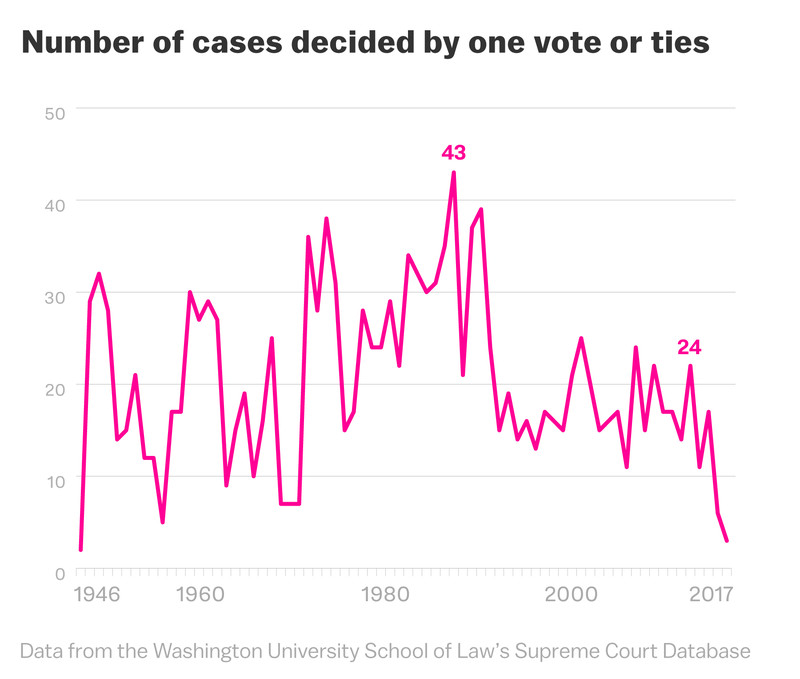

Yes, there are fewer 5-4 decisions these days, making the median justice perhaps less consequential, but several of those rulings have been on high-stakes issues like gay marriage and affirmative action — issues where Roberts has sided with his conservative colleagues.

The end of an era

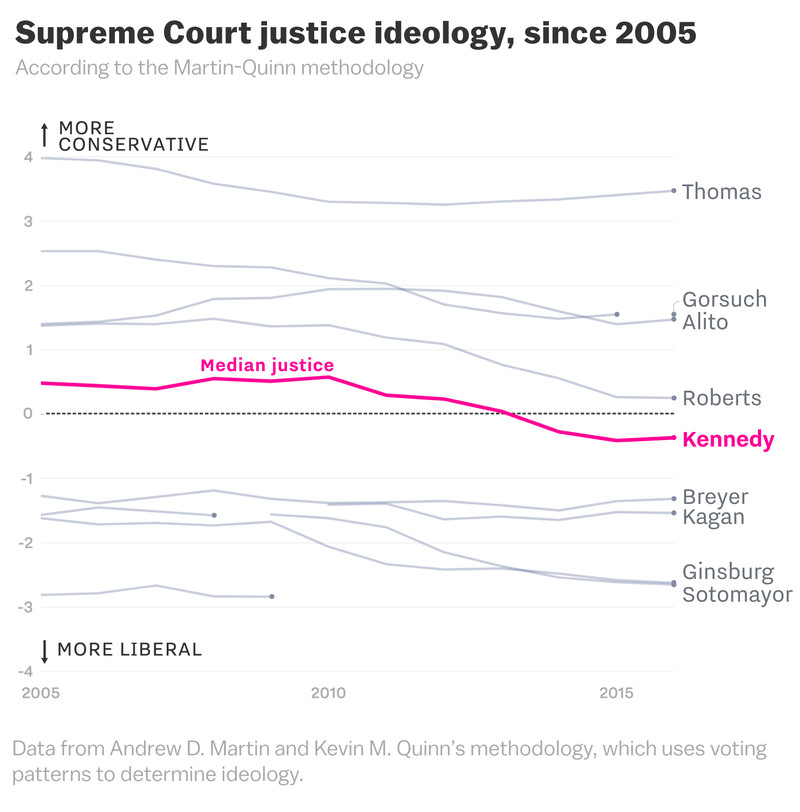

To grasp how influential Kennedy was on this court, take a look at this chart showing the history of the median justice.

During the 30 years Kennedy served, he was the median justice for more than half his tenure.

When he was confirmed, the median justice was Byron White, who retired in 1993. Kennedy then took the mantle for the majority of the ’90s, until Justice Sandra Day O’Connor occupied the middle as she settled into being more of a moderate.

Once O’Connor retired, Kennedy returned to the middle, and since then he’s had no true challengers from the left or the right.

Chief Justice Roberts, just 63, could hold the middle for at least the next decade — assuming the court’s composition stays the same.

A new appointment can drastically shift the ideology of the median justice

The median justice has, for the last 80 years, stayed near the ideological center of the court, though they have tilted conservative most of the time. Roberts’s ideological rating wouldn’t be out of the ordinary for a median justice.

But the court’s oldest members — Stephen Breyer (79) and Ruth Bader Ginsburg (85) — are liberals. If either of them were replaced by a hardline conservative, it would drastically shift the middle.

In fact, the court has often been one justice away from a drastic shift in the median justice’s ideology. The animation below first displays the median justice, and then it shows you where the next-most conservative judge would’ve been in each term. On the far right, you can see the shift the court is about to make:

We can see an equally big swing in the other direction, if we highlighted the next-most liberal judge in each term. On the far right, you can see the shift the court would’ve made had President Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, been confirmed in 2016:

To be sure, this analysis assumes that justices are acting in a vacuum, rather than adjusting their positions based on their colleagues’ stances.

But this volatility is why several court observers have called for ways to “fix” the Supreme Court. Vox’s Ezra Klein argues that the stakes of who sits on the Supreme Court are too high, and lands on term limits as a possible solution. Political scientist Lee Drutman argues similarly, saying term limits would make the court more predictable. This argument is usually made by the party that isn’t in the White House — but that’s not to say it’s invalid.

We see this volatility in McConnell’s maneuver that kept Garland off the bench.

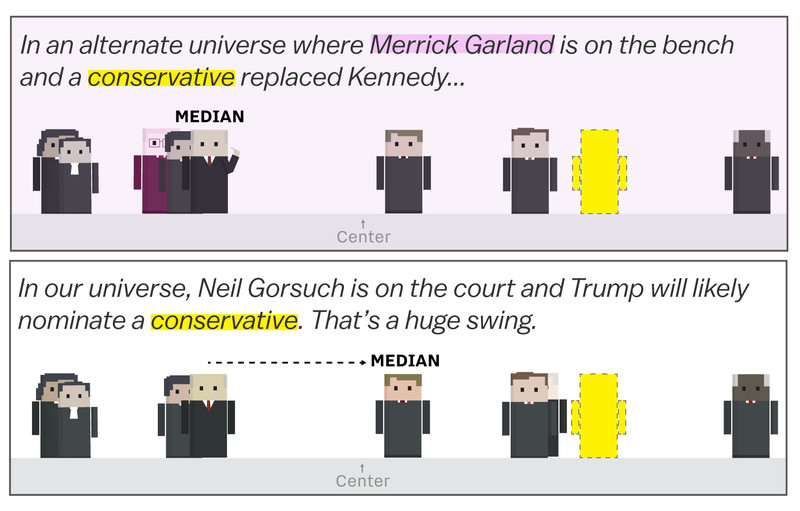

In an alternate universe where Garland was confirmed to take Antonin Scalia’s seat in 2016, Justice Stephen Breyer would have assumed the median justice role. Assuming Kennedy retired in June 2018 in this alternate universe (as he just did in ours), and he was replaced with a conservative, Breyer would’ve continued to be the median justice.

But, of course, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell never gave Garland a confirmation vote. Trump nominated a conservative in Neil Gorsuch. And if Trump’s nominee to replace Kennedy is confirmed, McConnell’s maneuver will end up swinging the court’s median justice from what would have been Breyer to Roberts. That’s a huge swing.

If we put stock in the influence of this median justice — and Kennedy certainly showed us we should — this data shows how fickle the court’s ideological middle can be. This fragile system allows an untimely death or an early retirement to drastically change the direction of American jurisprudence for decades.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png