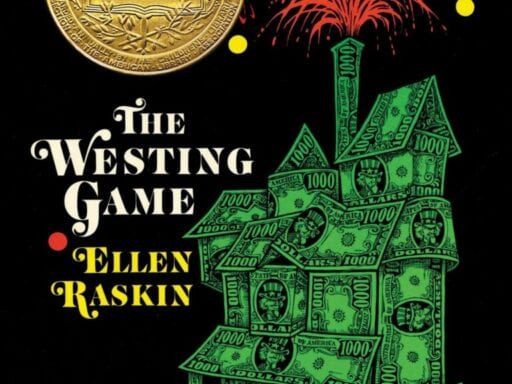

Ellen Raskin’s 1978 novel is a technically perfect mystery. It’s also ideal reading for when you need an escape.

Have you ever thought to yourself, “Wow, I wish I could experience Knives Out for the first time all over again, but this time I would like it to also be an extremely charming children’s book”? Then friend, you are in luck, for such a book does indeed exist. It is called The Westing Game, written by Ellen Raskin in 1978, and it is the perfect antidote to the quarantine anxiety blahs for readers of any age.

Like Knives Out, The Westing Game revolves around the will of a mysterious billionaire. Paper products tycoon Sam Westing — who would certainly have cleaned up in this, the era of toilet paper scarcity — has been found dead in his mansion. And 16 strangers have been named Westing’s joint beneficiaries, much to their bewilderment.

Adding to the mystery: All 16 of them have also recently moved into Sunset Towers, a glittery new apartment building on the shores of Lake Michigan that faces (the narrator points out helpfully) east rather than west, and has no towers. They were all rented their new units by one Barney Northrup, who, the narrator interjects, does not actually exist.

“Who were these people, these specially selected tenants?” Raskin writes. “They were mothers and fathers and children. A dressmaker, a secretary, an inventor, a doctor, a judge. And, oh yes, one was a bookie, one was a burglar, one was a bomber, and one was a mistake. Barney Northrup had rented one of the apartments to the wrong person.”

As the body of Sam Westing holds state in the hall of his mansion, dressed as Uncle Sam, his lawyer divides the 16 heirs are divided into eight teams of two. (No two family members can be on the same team.) Each team gets a set of “clues,” a collection of apparently random words written on slips of paper. The aim of the game, they are told, is simple: “to win.”

Baffled, the heirs retire in their teams back to Sunset Towers and try their best to work their clues out, each working through the lens of their own expertise. Perhaps the words are code for a chemical notation, suggests one heir. No, they’re stock market symbols, says Turtle, who is 11 years old and determined to be a businesswoman.

What ensues is a technically perfect puzzle-box mystery, one that baffled me when I was 9 and probably would baffle me today if I picked up The Westing Game without already knowing the plot. But it’s also a rich, paranoid allegory of American capitalism. There’s Sam Westing, the domineering and all-seeing Uncle Sam, dangling the opportunity for wealth over the heads of his resentful heirs. And there are the tenants of Sunset Towers, each one from a different social group, competing against their closest family members for the chance at $200 million.

Each of the heirs believes that to win, they have to work against one another. But the solution to the puzzle they finally reach suggests that to get their hands on the money, they’ll need to work together.

And in the end, it’s only precocious Turtle who grasps the true solution: to win the Westing Game, you have to understand that the point of the game was never to do what Uncle Sam told you to do in the first place. It’s to understand that the game is rigged and played by liars, and pass it by entirely.

But Ruskin, who trusts her child readers with hard truths, would never lie to us, and even though capitalism is a cheater’s game, she never cheats, either. That’s why this book endures: Ruskin tells us the truth when she builds her mystery, and she tells us the truth in her allegory, too. So whether you’re reading The Westing Game as a child or as an adult, you’ll always walk away feeling that you’ve been reading a book that respects you.

One Good Thing is Vox’s recommendations feature. In each edition, find one more thing from the world of culture that we highly recommend.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More