Society has undervalued care workers for centuries. Biden has a chance to fix it.

President Joe Biden’s $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan contains one particular provision that looks much different from physical infrastructure: $400 billion to make long-term care cheaper and raise care workers’ wages.

For health care policy experts, the need is obvious. Care work is a tough job. It’s also an essential service, and one of the fastest-growing occupations in a country with a rapidly aging population. About 95 million Americans will be 65 and older by the year 2060 (nearly double the number in 2018), ballooning the need for affordable in-home care. But in order to entice more people to do care work, many lawmakers and experts agree that these need to become better jobs.

For decades, home care has been defined as a profession with low wages, long hours, and scant benefits. It’s a job primarily held by women and people of color; 87 percent are women and 62 percent are people of color, according to a recent report from PHI International, a national nonprofit that advocates for home care workers. The average annual salary for a home health aide in 2020 was $27,080, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, about $13 an hour.

That was the wage that Chicago-based home health aide Adarra Benjamin, 27, made before the Covid-19 pandemic hit last year. Benjamin used to work up to 18-hour days shuttling between five clients, sleeping about four hours each night in between, she told me in a recent interview. The pandemic meant cutting back to one client — and she saw her income shrink by about half. Benjamin likes what she sees in Biden’s American Jobs Plan: She wants financial security and more normal hours when she feels it’s safe enough to add more clients.

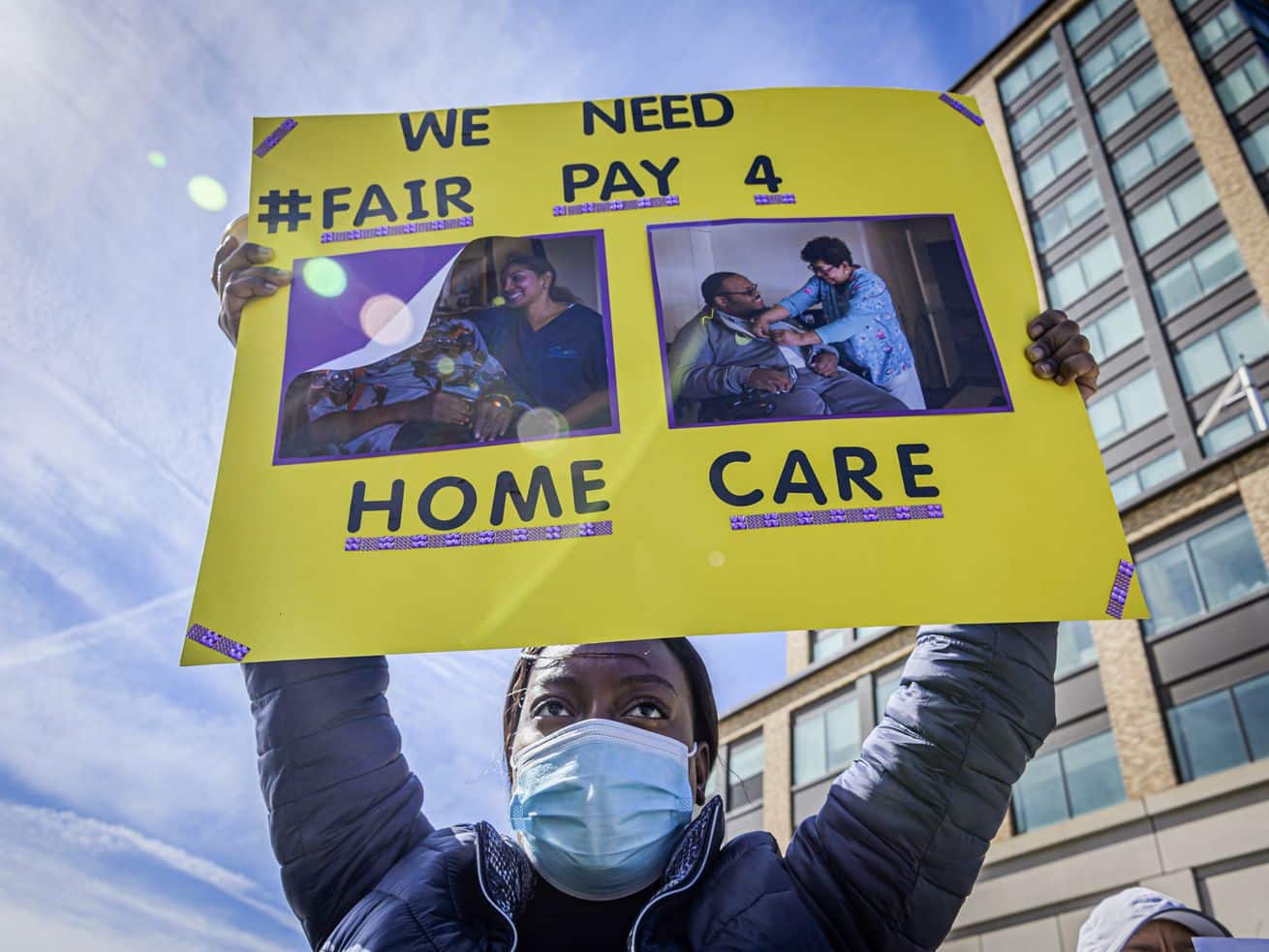

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22521258/GettyImages_1231612352.jpg) Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images

Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images“It would allow people to have a sense of a living wage, to not decide between transportation to work and food in the house,” Benjamin told me. “We know our worth.”

Underlying the fact that care workers’ wages have languished even as the profession grows is a long history of racial injustice, and a more recent reckoning on the history and legacy of slavery in America. The history of the profession goes back to the early days of America — domestic workers were mostly women cleaning homes, cooking meals, and caring for children and the elderly — and is deeply rooted in slavery.

Biden wants to cultivate an economic legacy akin to FDR’s; the progressive New Deal president’s portrait hangs prominently in the Oval Office. But that legacy has come under scrutiny in recent years for how Roosevelt approached racial equity, and because many of his New Deal reforms excluded jobs primarily held by Black workers — including domestic care.

Progress and recognition from the White House has only been made possible by years of organizing and activism from workers. And Biden’s administration employs a number of economists who have made boosting the wages of these workers their life’s work, including chief economist for the US Department of Labor Janelle Jones, who formerly led policy and research at Groundwork Collaborative.

“Receiving the respect, recognition, and compensation they are due is not only essential and necessary but it is just the beginning of what we must do to address the long history of racial exclusion that this workforce has faced,” Ai-jen Poo, the co-founder and executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, told Vox in an interview. “I think is a huge statement and a commitment to equity.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22520988/GettyImages_1232869830.jpg) T.J. Kirkpatrick/The New York Times/Bloomberg via Getty Images

T.J. Kirkpatrick/The New York Times/Bloomberg via Getty ImagesBlack women and people of color are important constituencies for Biden. The past few years have seen a reckoning on the racial wealth gap — hammered home by the Covid-19 recession. And after years of disinvestment in the field of domestic work, Biden has a chance to reverse that trend.

“If there was a moment to step in to bring a once-in-a-lifetime change to the home care industry … this is the moment,” said Celeste Faison, the director of campaigns for the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

How domestic work was excluded from the original New Deal

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s landmark New Deal agenda of the 1930s transformed the landscape of work in America — but not for Black domestic workers.

In the 1930s, lawmakers intent on preserving the racist order of the Jim Crow-era South carved out exclusions for domestic and farm workers from Social Security, minimum wage, and overtime laws — setting a standard of low pay and lack of benefits for decades to come.

“The basic template of America’s welfare state was set in the 1930s,” Theda Skocpol, a professor of government and sociology at Harvard University, told Vox. “Almost all occupations that Black people were in were excluded from the original version of the Social Security Act, but it’s a pattern that I would say persisted as long as the Democratic Party straddled the urban North and the one-party segregationist South.”

Even after the abolition of slavery in 1865, formerly enslaved people in the South continued to work mostly as sharecroppers or domestic workers in homes. Women initially did both of these jobs, but the vast majority were employed as domestic workers by the mid-20th century.

In 1890, 52 percent of Black women were domestic workers, compared to 44 percent who did farm labor, historian Jacqueline Jones writes in her book Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present. By 1940, a full 70 percent of Black women were working in private household service — a trend that was exacerbated by the Great Migration of Black families from the South to the North.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22521027/GettyImages_504216682.jpg) JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images

JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty ImagesLeaving domestic and farm laborers out of the New Deal wasn’t the original intent of Roosevelt’s administration. In a 1935 report drafted by Roosevelt’s Committee on Economic Security, the committee specifically mentioned “many who are at the very bottom of the economic scale” who could benefit from Social Security, including agricultural workers, domestic servants, home workers, and the self-employed, according to Columbia University political science professor Ira Katznelson’s 2005 book, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America.

Members of Roosevelt’s committee opposed excluding specific industries and workers from the 1935 Social Security Act, and recommended that all workers earning under $250 per month be mandatorily included. Still, other officials in Roosevelt’s Department of Treasury opposed including the groups, simply arguing it would be extremely difficult to collect payroll taxes from domestic and farm laborers. Whatever the intentions of Roosevelt’s administration were, they soon ran into the harsh political realities of the US Congress, and the factions within the Democratic Party.

In the 1930s, the Democratic Party could be roughly split into liberals and conservatives, many of whom were from the South. And while the Southern Democrats broadly supported making labor laws friendlier for workers, this did not extend to Black workers.

“You cannot put the Negro and the white man on the same basis and get away with it,” wrote Democratic Rep. James Mark Wilcox of Florida in the late 1930s, as the Fair Labor Standards Act was being debated. “We may rest assured, therefore, that when we turn over to a federal bureau or board the power to fix wages, it will prescribe the same wage for the Negro that it prescribes for the white man. Now, such a plan might work in some sections of the United States but those of us who know the true situation know that it just will not work in the South.”

The Southerners didn’t need to push very hard to get liberal Democrats to capitulate to their demands. Katznelson noted that even leading pro-civil-rights Democrats, including New York Sen. Robert Wagner, “were prepared under pressure to jettison the people whose inclusion the South most feared.” That, combined with the fact that Southern lawmakers chaired multiple key committees, meant that first drafts of bills like the 1935 National Labor Relations Act that allowed farm and domestic workers to organize were later tweaked to specifically exclude such provisions. “These changes met with a virtually total absence of any criticism by non-southern members of Congress,” Katznelson concluded in his book.

Liberal Democrats in Congress had a calculation to make: They could either abandon Black workers or stand firm to Southern demands and risk tanking the bills altogether. Ultimately, they chose the former.

“They had to put together the coalitions, and a lot of times they did it the same way everybody does now, just exclude things a blocking coalition would refuse to accept,” Skocpol said.

By the time Congress was considering the hallmark Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, other major bills had already been passed excluding domestic and farm workers — setting the standard. In 1938, women domestic workers weren’t even explicitly mentioned in the text of the Fair Labor Standards Act, but they “were effectively excluded by virtue of the law’s narrow embrace only of workers ‘engaged in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce,’” Katznelson wrote in his book, adding, “by now, these exclusions seem to have been taken for granted as a condition for passage.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22521166/AP_3003060161.jpg) AP

AP“I do think it’s fair to say [with] domestic work, the obstacles were even bigger than agriculture because you also have the gender biases and also the sense of the home,” said Eric Schickler, a professor of political science at the University of California Berkeley. “If there’s a usual workplace, it has some public character to it, whereas the home is the most private.”

Social Security benefits were extended to these groups starting in 1950, but it would take until 2013 — a full 75 years — before millions of domestic workers enjoyed the benefits of the fair wage laws passed during the New Deal era. Live-in caregivers still are barred from accessing these protections, as are “caregivers who spend less than 20 percent of their job helping clients do basic tasks,” Alexia Fernández Campbell reported for Vox in 2019.

Domestic workers are starting to get the recognition they’ve been fighting for

The percentage of Black women who worked in private homes decreased steadily during the 20th century, due in part to civil rights and equal employment legislation in the 1960s. That number fell from 70 percent in 1940 to 33 percent in 1960, cratering to just 6 percent in 1980. By the 1980s, most Black workers in service jobs were working in health services, economist Julianne Malveaux found.

As of 2017, Black workers had their highest representation in the medical field as nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides, where they made up 32 percent of the workforce, according to American Community Survey data gathered by the US Census Bureau. Black workers also accounted for about 22 percent of personal care aides, the data showed. And Black women made up 40 percent of those employed in education and health services as of 2018, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“It’s work that’s naturalized as the labor of women and people of color, and historically over many generations, it’s not considered real work that’s worthy of recognition and compensation,” said Kezia Scales, director of policy research at PHI International.

That view is slowly starting to change, with academics and activists laying a foundation of historical evidence that care work has for decades been an underrecognized profession. Biden’s administration has consistently mentioned racial equity as one of its top goals, and it employs a number of economists who have worked specifically on how to raise wages for women of color.

“I’m a Black woman. I center Black women in a lot of my thinking,” Janelle Jones, the Labor Department economist, told NPR recently. “But I think you can really apply this to all types of groups that we usually don’t center.”

The profession is also getting more protection from federal laws. In 2013, the Obama administration updated Labor Department regulations known as the Home Care Rule to extend the Fair Labor Standards Act to about 2 million home care workers who were previously excluded. And Biden placing long-term care workers in his centerpiece infrastructure proposal — the American Jobs Plan — is a nod to the profession.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22521212/_P9A2033.jpg) Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/Vox/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22521215/_P9A2120.jpg) Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/Vox/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22521216/_P9A1790.jpg) Christina Animanshaun/Vox

Christina Animanshaun/VoxIt also comes after centuries of organizing and protesting by domestic care workers themselves. Indeed, Black women workers had been organizing themselves since the 1800s, during multiple washerwomen’s strikes across the South, demonstrating for higher wages. And in the 1960s, domestic worker Dorothy Bolden helped create the National Domestic Workers Union of America, an organization of Black women workers to fight for better jobs.

“A domestic worker is a counselor, a doctor, a nurse,” Bolden told the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution in 1983. “She cares about the family she works for as she cares about her own.” But, she added, these workers “have never been recognized as part of the labor force.”

More recently, then-Sen. Kamala Harris introduced a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in 2019, in Congress alongside Rep. Pramila Jayapal — reforming labor laws to include caregivers and nannies, and extending them benefits such as paid time off.

Women and people of color were crucial to Biden’s presidential win, and they are also crucial elements in his jobs plan. And time is running out to make these jobs more enticing; America’s rapidly aging workforce and high costs of long-term care are colliding, keeping more women out of the workforce to care for aging parents or children with disabilities.

Benjamin, the Chicago-based home care worker, loves her job. But she also wants it to be a better job, for her and for the next generation of workers. “I’m 27. I know in 20 years that my daughter or granddaughter, [future] generations, are still going to need this job,” she told me. “It’s time we start looking at it as a system that’s important rather than being left on the back burner. Without us, there will not be anyone to keep the ship moving.”

The domestic workers who were left out of the New Deal have a chance to be prominent parts of Biden’s economic agenda. But they recognize the fight is not over.

“Our membership is fired up,” said Faison, the director of campaigns for the National Domestic Workers Alliance. “We have a directive from our home care workers to go and get it.”

Author: Ella Nilsen

Read More