Can you remember your first experience with the police? For these 9 Black and brown people, the encounters would shape their sense of safety forever.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21869561/highlight_epic_logo.png)

It was a warm Sunday afternoon in late May when a friend mentioned he was organizing a Black Lives Matter march near my home in San Francisco. Like many, I hadn’t left the house in weeks; the city was in lockdown, and Covid-19 was well underway. But despite my fears of getting sick, something told me I needed to go — that I needed to show up for my community. So I decided to go alone.

We walked on Market Street, circling the Embarcadero twice in a peaceful protest of the deaths of George Floyd, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, and so many more of my fallen brothers and sisters. We had been marching for two hours and were just about to start a third loop, when suddenly, an unmarked white van approached us, blocking our path. A slew of other unmarked vehicles followed. Several heavily armed police officers flooded the sidewalk, forming a line around the building we had just passed.

Immediately, as if by instinct, all the people of color stepped into the street, away from the police, just as two white protesters stepped forward. They got into the officers’ faces, screaming and yelling, calling them pigs. One of them moved even closer, till it looked like it might escalate into something physical. A short Black woman with dreads and a loudspeaker screamed for them to step back. “This isn’t helping!” she yelled.

But they didn’t stop.

In fact, one of them continued walking up and down the line, eyeing the officers. Unafraid and untouched.

Their audacity shocked me. I was struck by the deep divide between how those with less melanin reacted to the police, compared to those with more — and how young I and so many others were when we were forced to learn to be cautious with those sworn to protect us.

I thought about my first interaction with law enforcement, when I was just 10 years old. I thought about how traumatic it was, and how that experience shaped me into the person I am today: someone who knows that law enforcement isn’t always right, and who speaks up when she sees injustice. And I thought about how different it must have been from the experiences of those two protesters, who felt they could yell at a line of officers without deadly consequences.

I also thought that if people, allies or not, could hear our stories, maybe they would finally listen and would understand why we are marching for change. Why we need change. Since our march, with the killings of Rayshard Brooks, David McAtee, and so many others at the hands of police and the National Guard, our calls have only felt more urgent.

After that day, I started talking to people. I posted a callout on social media asking them to share their first, most impactful experience with the police — good or bad. The post spread. I began to get countless messages and texts from people I knew, and many I did not. Most of their stories were unpleasant and abusive. Of the dozens of people I spoke with, almost everyone struggled to come up with a positive experience. I opened up my old scars, and those of the people brave enough to share their stories with me — stories of hurt, disdain, aggression, privilege, corruption, occasional kindness, and very little understanding.

These are just a few of these stories, told over several conversations and edited for length and clarity. Each is unique, and a different lens on the complex relationship between citizen and officer.

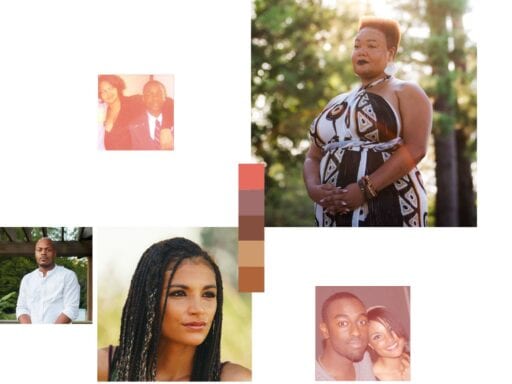

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867614/Rabi_1_2_wide.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867619/Rabi_3_4_wide.jpg)

Rabi Basir

Now: 46

I was 15 years old, and I had just gotten off from work. I was planning to meet some friends at a party, so I took the bus to my cousin’s house to change clothes.

I walked in, and everyone was in the living room watching the BET Awards. My cousin had a couple friends over, her kids were there. I said hi and went straight to the bathroom to get ready. I couldn’t have been in the house more than 15 minutes when I heard a huge bang, so loud that it literally felt like it shook the house. Before I had time to think, I heard people running up the stairs and kicking in doors. The kids all started screaming. Then I heard the cops say, “Freeze! Everybody get on the floor!”

I started thinking to myself, Oh, crap. Do I stay where I’m at, or do I open this door? I don’t want to surprise them, and if I open the door too quickly they might think I’m a threat, and I don’t want them to shoot me. But before I can figure out what to do, they kick in the door and put their shotguns in my face. I was so scared. I was just frozen there for a moment, because I wanted to seem as nonthreatening as possible. I move slowly, I have my hands up, and I get on the floor. I look up and I see that they all have on these vests that say SWAT.

Then a female officer steps in and says, “I’m going to need to pat you down.” I have on a skirt, and she tells me that she needs me to take down my underwear. I was a child, alone in the bathroom with someone I didn’t know, who made me disrobe so she could search me. Again, they didn’t call my mother for consent or anything. I was a minor.

Out in the living room, they’re lining everyone up on the floor. They’re pulling people aside, asking them questions about drugs and all this other stuff. After searching me, they bring me to the living room, too, and one of the guys says to the other one, “Yeah, this one was in here flushing the dope down the toilet.” And I’m thinking to myself, “The hell is going on? What dope?” But then another officer says, “No, I think she just got here, because I saw her when she got off the bus and walked down the street.” So they were aware that I didn’t have anything to do with this operation, and they still made me take off my underwear and bend over so that officer could search me.

After a while, they realized they were in the wrong house. My cousin lived on the top floor of a duplex. They were supposed to search the house on the first floor. They didn’t find any drugs or anything illegal, but they needed to justify what they had done, so they said they were taking a few of us to jail. They pointed out the ones that they wanted to get in the van. I happened to be one of them, because I was “outside after curfew.” They also took my cousin’s friend, and then another girl, who was actually younger than me. I think she was, like, 13 years old.

It is traumatic as a teenager getting carted off to jail for not doing anything. It’s embarrassing. It’s demeaning. You feel like a second-class citizen. Everyone in the neighborhood sees you get loaded up in that van. Everyone gets to see them cart you off, like a criminal. Like my grandmother used to say, in the perp walk.

I was at the precinct for roughly an hour. My mother had to come and get me, and she came in the door cursing them out.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21872826/rabi_5_it_is_traumatic.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867630/Rabi_6.jpg)

The next day, I went back to my cousin’s house to check on her, and one of her friends — the one who got arrested — comes up to me. She’s like, “You need to mind your business. The police told me that you told them I was selling drugs or something.”

Luckily, my cousin jumped in and was like, “Does that even make any sense? Why would she come here the next day if she had snitched?” I don’t think the cops realize, in the Black community, when they try to label people as a snitch, how far people will take that information. People get hurt! I don’t know what would have happened if my cousin didn’t step in for me.

It made me look at the police differently. I never thought they would lie about me. When they kicked that door in and put those shotguns in my face, I can’t even explain to you how that felt. How do you prepare a person for a situation like that? I mean, I literally felt like I was about to die.

Police officers have in their mind exactly how they’re going to perceive us, whether we say or do anything wrong or not. Even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, they’re going to find a way to justify it. Even if it isn’t true or right. Even if it’s the wrong house. They think to themselves, “They’re a bunch of animals and savages.” And so they prepare themselves to deal with animals and savages.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867607/R_1_2_wide.jpg)

R. Gippetto

Now: 33

I’m a US citizen, but I grew up in the Caribbean, around mostly Black and Latino people. Also, my mother was a police officer. But not just any police officer: She worked for internal affairs. She policed the police. So when I moved to Georgia at 18, my understanding of the police force was that only the good officers stayed; the bad ones were fired. But all that changed after I moved here.

So I was 19, my laptop was broken, and I needed to finish a job application. All of my friends were busy, and I couldn’t borrow their laptops, so I went to the library. At the time, I had just started my locs and I hadn’t had a haircut for a couple of weeks, so I put on a durag to cover up my hair and threw on a hoodie because it was kind of chilly.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21873337/R_3_up_until_that_moment.jpg)

As I was walking along the side of the library, no more than a block away from the entrance, a police officer patrolling the parking lot said, “Hey, take that durag off.” I’m outside, just walking by myself, so I didn’t pay him any attention. Then he repeats, “Hey, take that durag off and pull your hoodie off your head.” I looked at him and said, “Sir, I don’t have my hair cut and my hair’s not bothering you, so you have a good day.”

I turned and continued walking to the library, but then the cop sped up, hopped out of his car, and blocked me off. Then he put his hand on the library wall, pinned me to the side of the building, and moved an inch away from my face. His other hand was now on his gun. He repeated, “Look here, boy. I told you to take that durag and that hoodie off your head. Now.”

Up until that moment, I still didn’t think he was being for real. I’m just thinking to myself, “Are you serious?” My face was clearly visible — my hoodie wasn’t over my face. So I asked him again, “Why do I have to take it off?” And he said, “Because you look suspicious, and I need to be able to see your whole face.” I tried again. I said, “Sir, I really don’t understand. I’m just going to the library to finish a job application.” Then he responded, “I said you better take that off right now or else you’re going to be in for a world of trouble, and you’re not going to be going home tonight.”

I could tell I didn’t fit a “description” — that this cop just wanted power over me. But I was terrified. He still had his hand firmly on his gun. He would not let me move. I just had to accept defeat. I pulled my hoodie off my head and took my durag off. My hair was looking crazy, and he’s like, “That’s what I thought. Now you can go about your business.” So I walked toward the entrance of the library while he watched me from his car. Once I turned to enter, he drove off.

Before that, I’d always had a reverence for police. I was never somebody who thought all police are evil. When I first moved to Georgia, a lot of my Black friends would say to me, “See what that white person did? That’s racist.” But I was unfamiliar with microaggressions, so I didn’t catch those cues at first.

Back on the Virgin Islands, I didn’t have any one-on-one interactions with racist white people. So I would always play devil’s advocate with my American friends — like, yes that person was kind of short with me, or kind of rude, but maybe they were just having a bad day.

But when I got home that day, I started calling my friends, saying, “I get it now.” It had to happen to me for me to be like, damn, this is for real. I can’t just walk around thinking this is the land of the free. I am a Black man in America. My eyes just totally blew open.

I always wonder what would have happened if I’d given the officer pushback. If I had walked off with my durag on my head, what would have happened. Black people, we all have that little sense in us. But I truly feel that a shift is happening, and must happen, because we can’t deal with this no more. We as Black people can’t keep running around, shuddering at the thought of something tragic happening to us at any point in time.

Breonna Taylor — they kicked in that woman’s door and killed her. When I saw that footage of Ahmaud Arbery, I stopped jogging in my neighborhood, because I don’t even want that to be a possibility. When it happened, the Trayvon Martin story really stuck with me and put a knot in my stomach and my heart — because he had on a hoodie, he looked “suspicious.” And Trayvon Martin was walking away.

That particular story stays with me. This young Black man who “looked suspicious” was minding his own business, and somebody took it upon themself to take his life. It just brings me chills, because what if I had just blown the officer off and walked away? He likely would have shot me and said he thought I had a gun. I know that’s extreme, but after what he said, having his hand on his gun — I might not have made it home that day.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867645/R_D_1_2_wide.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867646/R_D_3_4_wide.jpg)

Diamond Collier and Rakim Rowley

Now: 39 and 30

Diamond Collier:

I was in college, back home to see my family for the holidays. At that time, my younger brother was staying with my grandmother because our mother was in the prison industrial complex of the early ’90s. When I came home, I saw he wasn’t being taken care of in the way he should have been — like he didn’t have a coat or enough clothes. And it was in the middle of winter.

I came to realize my grandmother was navigating sobriety. So I called my mother and I told her what was going on. She immediately filed papers for me to get guardianship of my brother. I had to drop out of school and move in with my aunt and her six kids to take care of him.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867650/R_D_5.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867651/R_D_6.jpg)

Eventually, I got a job at a tech company, and I worked, worked, worked, and saved, saved, saved. After two months, I was able to find us a duplex with enough space for Rakim and me. Then, right after we moved in, my supervisor called me into his office and fired me for being trans. It was 2002. I was a great worker, and I hadn’t been written up before, but I lived in a state that didn’t have protections for me.

I tried looking for another job, but I didn’t have my name changed on my ID, so I would go to the interview and then never get a call back. I’m not saying I didn’t get the job because I was trans, but I could tell once they found out, the interview changed. I didn’t have a job, I was running out of savings, and I had my younger brother to take care of — so I turned to sex work. I had never done it before, but I had no option.

When I started, I set up a system where Rakim would know if I had a client or not and stay away from the house, so he had no interaction with the people coming over.

Rakim Rowley:

Zero interaction.

Diamond Collier:

On this particular day, I was upstairs with a client, and where were you, Rakim?

Rakim Rowley:

I was with my friends down the street, and we’d decided we were going to play some basketball. They didn’t have a ball, so I said, “Well, let me go to the house real quick and grab mine and I’ll meet back up with you.” I got to my backyard and noticed that the signal was out. At the same time, I also noticed someone standing on the side of the house.

Diamond Collier:

We never had random guests. After a previous incident at Rakim’s school and being fired from my job, I was hyper-aware of how my transness could affect him. So people didn’t come to the house. I had queer friends, but we would hang out at other places. I didn’t want to bring attention to my house, and I didn’t want him to be shamed for having a trans sister.

Rakim Rowley:

So when I see this man on the side of my house, I am thinking, What’s going on over here? As I walk toward this person, I hear them say, “Let me see your hands.” It’s not registering to me what’s happening, and I can’t see his face, so I keep walking forward, and then he says, “Put your hands up right now.” And I can plain as day see a gun.

In my head, I really thought it was a robbery. We’re in the inner city, Indianapolis. Nobody has nothing. Everybody is trying to look for a come-up. We live in a neighborhood where these are regular, everyday people fighting for survival. So to see someone and to hear that — what’s going on in my mind is, Dang, my time then finally came. It was a surreal moment.

I was never told, “This is the police,” or anything. I didn’t see any badge, I didn’t see anything but a gun and a heavy jacket. The guy was in plainclothes, so I didn’t know he was an officer until he took me to the front of the house, where these people in uniform were gathered. Then he says to me, “We need to get in your house. Go in the house and let us in.” I’m like, “All right.” ’Cause I’m a 12-year-old child, and when you’re a kid, you’re always taught the police are your friends.

When I walk in, I see Diamond walking down the stairs.

Diamond Collier:

We are looking at each other trying to figure out what is going on, because Rakim wasn’t supposed to be in the house.

Rakim Rowley:

Meanwhile, the guy she was with comes down, walks past her, and opens the front door. At that moment, we realized something was up.

Diamond Collier:

It was a sting. They sat us down, and I explained what I was doing, and the officers started having these weird-ass fucking conversations about how I’m this young guy’s “big brother,” I shouldn’t be doing this, “What you are doing is wrong and you should be ashamed of yourself.” It didn’t matter that I was the only one in my family who stepped up to take care of him and that I was unfairly fired.

Rakim Rowley:

The officers kept referring to her as “him,” “he.”

Diamond Collier:

“Him,” “Sir,” “You’re the big brother.” It was really disrespectful. You would think on the outside looking in that maybe they’re just trying to teach me something, but no, they weren’t trying to teach me anything. They didn’t care about this little Black boy, because if they really cared, they could’ve come back and said, “Hey, we’re going to try to get you some help and assistance. Let’s get your younger brother in some programs. Let’s try to get you a job somewhere. How can we help you in this situation?” But that wasn’t the case. They just wanted to shame me in this moment because of their transphobia.

Hindsight is 20/20, so I can talk about it clearly now, because I understand the politics of white supremacy and patriarchy and all that kind of stuff, but in the moment, I didn’t. I was only 22. All I knew was to sit there and comply because they were cops.

Rakim Rowley:

That same homophobia and transphobia clearly dictated how everything was handled. They didn’t find any drugs or guns. They knew Diamond was in sex work, and she told them she was taking care of me. After that, they could have said, “Yes, we see what you are doing, and we are going to write a citation. This is the citation; this is when you will appear in court. Have a nice day.”

But they abused their authority. You approached a 12-year-old — I couldn’t have been bigger than 100 pounds, 5-foot-4 at the time. You pulled your gun on me, on my property, while in plainclothes, without knowing how I was going to react to the situation.

What would have happened if I had run away because this is a person in plainclothes? This is a stranger. I’m afraid …

Diamond Collier:

… Because you got a gun in his face.

Rakim Rowley:

… or I’m angry, I’m upset. Let’s just say I had an aggressive tone to begin with because I didn’t know who this person was in our yard. What could have happened? What was the unnecessary aggression for? Why did you come here with a preconceived notion that I am going to have a gun out? Even when they could see I wasn’t a threat, the gun the first cop pulled never went away.

Diamond Collier:

That is because the police state is an arm of white supremacy in direct opposition to our existence. In that moment, and now, they will never be equipped to see my humanity. Therefore their ability to protect and serve me will always be insufficient and lead to more oppression instead of liberation or safety.

When it happened, there was fear there. I’m thinking, I’m about to get locked up. And what happens when the trans woman who has custody of her brother gets locked up? They go into the system — the whole thing that I was trying to keep from happening to my brother in the first place.

Luckily for me, in Indiana, they don’t actually lock you up for sex work — which I didn’t know at the time. They just give you a ticket. And that’s what they did, then told me I had to go to court. I was like, “Just a damn ticket? A $250 ticket?” The crazy part is when I went to court, they had the wrong girl’s info on my file. It wasn’t my picture. It was a different voice recording as evidence. It was this white girl who don’t sound nothing like me. The judge was like, “This is not her. Get this shit out of my face.” And they threw it out.

Rakim Rowley:

I didn’t even know that part.

Diamond Collier:

I didn’t have to pay $250; I didn’t have to go to jail. I just went home.

Rakim Rowley:

In hindsight, I can chalk it up to my youth and being naive. I was sold the idea that police were the neighborhood saviors, but that day, I learned how I really needed to see them. They didn’t care that Diamond took care of me. They weren’t there to save anyone. And to this day, I still get harassed in the same way. And I’m a veteran. I fought for this country, and they don’t care.

Diamond Collier:

I never trusted police officers after that. They weren’t there to help me. They didn’t care. It don’t matter if you’re a good officer: If you’re working in a system that is broken, it don’t matter if you’re good. It don’t matter.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867656/I_1_2_wide.jpg)

Isaac Osei

Now: 40

Growing up, I lived in the Bronx, but I went to high school about an hour away at Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics in New York City. On this particular day — I was a sophomore or freshman — I was returning home from school. I had just gotten off the bus, and I was about to make a turn onto my street when an officer approached me from behind and said, “Hey, can I ask you a few questions, please?”

For the most part, I was a pretty easygoing kid. I didn’t get into a lot of trouble, and I was brought up to trust the police. Also, I’m an immigrant — and at the time, I hadn’t had a lot of interaction with law enforcement. My family is from Ghana, and we immigrated to New York in the early ’80s. So when the cop asked if he could speak with me, I didn’t mind. I figured he was just looking for somebody or something, and it had nothing to do with me, obviously. Also, I believed he could have been Hispanic. I didn’t get the sense that he was a white male, so I trusted him. I thought he was part of my community.

So he says to me, “Where are you coming from?” I have my backpack on, so I just kind of indicate with my head that I’m coming from school. Then he asks if I’ve been around for long. I’m like, “No, like I said, I’m just coming from school.” Then a shorter lady comes from behind the officer, and he goes, “Is this him?” And she’s like, “Yeah, yeah — he looks like one of them.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21873803/isaac_3_i_was_less_than.jpg)

At that point, I still wasn’t sure what was happening. Then the officer says, “Well, this lady said that you were part of a group that stole her purse.”

I was kind of shocked by it. The whole time, I was thinking this is a misunderstanding — I hadn’t done anything. I was less than 200 feet from my house. I still didn’t really grasp the magnitude of the situation, until the cop says, “Well, we’re going to have to take you down to the station and talk to you some more.” They ended up cuffing me and putting me in the car.

When I got to the station, they put me in a room by myself and left me there for a while. No one talked to me for a few hours, and then all of a sudden, there was a knock on the door and they said, “All right, you can come out now. Your dad’s here.” As my father was filling out some paperwork, they explained, “Yeah, we found the perpetrators. You’re free to go.” The whole thing was a head-scratcher, because the cops had barely talked to me.

It was kind of embarrassing, having my dad come to the station to get me. And when my dad asked me about it afterward, he sounded disappointed. It was also embarrassing because I was a pretty good kid. I never ran with the wrong crowd, it wasn’t part of my personality, and then my dad had to see me come out of this jail.

It was kind of traumatic, in a sense. Fortunately, nothing really bad came out of it, but it definitely opened my eyes and made me realize, Hey, I’m not a kid anymore.

What impacted me most was learning that anyone could use the police against me. The simple fact that a woman could say, “Yeah, that’s him,” was enough to take me to the precinct. It was enough for everyone to think, “You’re the guy.” I haven’t experienced anything overt like that since, where I was detained or arrested. But I became a bit more cautious in terms of dealing with the police after that, because I learned they didn’t see me as innocent.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867666/L_1_2_wide.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867667/L_3_4_wide.jpg)

Lynarion Hubbard

Now: 36

I had just graduated with degrees in TV/film and computer science from the University of Miami, and I was ecstatic. It had always been my goal to go to college and get a degree. I remember walking across the stage, and feeling so happy that I had done it — especially within four years, because I was a double major.

It was a really hot day. A lot of my family had come. My dad’s two sisters and their husbands had driven down from Georgia. My grandparents on both sides of the family had driven down, too. My mom and her siblings were there. To celebrate, we were all going to gather for dinner downtown.

As a student, I was allowed to park on campus, so after the ceremony, I volunteered to drive my grandmother to her car at the commuter lot, which was being used for guest parking. I took my uncle and one of my close friends along for the ride.

I had to make a left-hand turn into the garage because of the direction I was coming from. The traffic cops — one Miami cop and two campus cops — were supposed to be directing cars, but they were off on the sidewalk talking. There weren’t any signs saying I couldn’t go into the lot because of graduation, so I turned into the garage.

Before I could even pull into the driveway, the Miami cop walked in front of my car and stopped me from going any further. He didn’t say anything, just crossed his arms. So I rolled down my window and I was just like, “Sorry, I’m not trying to park, I’m just dropping my grandmother off at her car after the ceremony.” But he didn’t respond.

At this point, I am still fully dressed in my graduation gown. I don’t have my cap on anymore, but it’s clear that I’m a graduate. There’s no confusion that I was a student, that I’m someone who had permission to be in that lot. But instead of arguing, I tell my uncle to walk my grandmother to her car.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867669/L_5.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867670/L_6.jpg)

I have no idea why this cop is being so difficult. But I attempt to put him out of my mind and reverse the car so I can head out to meet the rest of my family. I’m trying to safely finish my reverse three-point turn without hitting any cars. People stopped their cars to let me finish. But once I got into a position to go straight, the Miami cop walked around the car and said, “License and registration.”

… I was like, are you kidding me?

But you don’t argue. My purse was on the floor of the passenger side, so I put my car in park and reached down to grab it. Then my friend started screaming, “He’s got his gun! He’s got his gun!” And I look to my left, out the driver’s side, and the cop has his gun out, pointed at my face. He’s yelling at me, “You tried to hit me with your car!” In that moment, I went on autopilot. All I knew was, I don’t want to die today.

I don’t remember everything that happened next, but I do remember unbuckling my seat belt, opening the door, and turning around to get handcuffed and walked to the sidewalk. I don’t even think I turned the car off. I’m sitting there on the curb, hyperventilating, bawling, and wondering to myself, What is going on? I hadn’t realized it, but a crowd had grown around us, and everyone — including some of my classmates — had started yelling in my defense. They had witnessed what had happened and could see no reason why the cop had responded the way he did.

After 15 minutes of discussion between the Miami officer and the campus police, the officer came over and said, “Well, I’m not going to arrest you, but here’s my card, and if you have a problem with what happened, you can go talk to someone downtown,” and then he uncuffed me.

That was it. There was no apology. He even had a smirk on his face.

I don’t remember the rest of the day after that. I don’t remember going to dinner. This was supposed to be my day, and he’d completely ruined it. He had embarrassed me, not just in front of my family but my peers and my friends. I just shut down.

A few weeks later, I went to the Miami Police Department to file a formal complaint, but it was futile. It was just, “Oh, we’ll put it on his record.” But nothing ever came of it.

After that, what I realized is, as a Black person, it really doesn’t matter how you present yourself. All that matters is how the police view you. I can think I am a good person and that I don’t get in trouble, but none of that matters. We’re not worthy of the benefit of the doubt. We’re not even worthy of sympathy. I just don’t believe that if I was a blonde, white girl in that car, the cop would have reacted the way he did. I mean, I was in my cap and gown, during my graduation, on my campus — and none of that mattered at all.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867680/Y_1_2_wide.jpg)

Yunus Coldman

Now: 62

I was taking the subway home from school, and I had a lit cigarette in my hand. It was 1973, I was 14 or 15 — still in high school — and I was with some classmates. I was being very bodacious and walking around like I was somebody and didn’t have a care in the world. Then, as I was transferring at 42nd, going to the next train, a police officer stopped me. And I froze.

I was scared, really scared, because I knew I shouldn’t be walking through the subway with a cigarette in my hand. You weren’t allowed to smoke in the subway, and the cop had a gruff, serious look on his face. He asked for my name and phone number and told me that he was going to call my mother.

I didn’t know what my mama was going to do if she found out that I was walking around like I’m grown, smoking a cigarette. At the time, I didn’t have strong feelings about the police, but I was afraid of him telling her.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867681/Y_3.jpg)

After the cop took my information, he told me to go straight home, and I did. For a week, I was terrified he was going to call my mother. But I waited and waited, and it never happened. Years later, I realized what he’d done: He’d made it look like he was creating a report to scare me into doing the right thing to make sure I never did it again. And it worked. It absolutely worked.

Unfortunately, however, my second experience wasn’t as positive.

I was around 33, 34, and I was strung out on crack. I was actually on my way to secure some drugs. I had been addicted for about six or seven months, and I wasn’t really a very good drug addict. I never really looked around and paid attention, trying to spot anyone who might be looking for me. So I didn’t notice the police car until they were right on me, blocking my passage. To me, it was like they came out of the blue. A female officer jumped out and began to frisk me and tell me, “I’ve been trying to catch you for the longest time. I’ve been waiting for this opportunity.”

In that moment, everything seemed to go really fast. In all honesty, my mind was still focused on going to get the drugs — my body needed it, my mind needed it, I needed it. But the cop went through all the motions and found nothing. She was quite disappointed, I’m sure. Realizing there was nothing on me, they had to let me go.

The thing is, I had lived in that neighborhood for eight years. Had she really been watching me, she would have realized that something was wrong.

I was hurt and hitting rock bottom. Instead of trying to “catch me” doing something illegal, to arrest me and put me in jail, she could have helped me. Asked me what was wrong. Said, “Okay, I might have to arrest you now, but we’re going to try and get you some help.” Anything but, “I’ve been trying to catch you.” Because in my mind, that really just meant, “You’re just a worthless piece of shit.”

With both of my experiences, there was an opportunity there. There was a choice. In the first encounter, the cop chose to help me learn — he chose to lead me on a path of the law. He helped me get my shit together. But in the second incident, they chose to mess me up. If they would have tried to help, my bottom might have been different — I might not have lost everything. And isn’t that what “protect and serve” really should be?

It is almost 30 years later, and I’m still hurt from it, even though I have been sober and clean for almost as long. Police aren’t supposed to be feared. They went from being peacekeepers and helping people to thugs and criminals. And just like I devolved when I was on crack, I look at them as devolving: It has gotten worse and worse and worse and worse.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867707/S_1_2_wide.jpg)

Sham Ibrahim

Now: 40

I’m gender-fluid, in the process of transitioning to female, but when I was 18, I was still exploring my gender identity, experimenting with makeup and women’s clothes and things like that.

It was 1997 or 1998. I was high, I was partying. I had just left this guy’s apartment in the Tenderloin. I had on tight-fitting pants and a kind of blouse thing, and I had eyeliner, and I had long bangs. I wanted to be more feminine-looking, but at the time I would say I was more androgynous.

I was walking down, I believe, Eddy and Hyde. And as I was walking, I heard the word “fa**ot.” The next thing I know, somebody grabbed me by the neck, and another person hit me in the face with — I don’t know if it was brass knuckles or something, but they hit me so hard in the face that I fell backward.

It happened so fast. I was spitting blood everywhere, and the first thing I noticed with my tongue was that I could feel my front teeth were pressed against the roof of my mouth. Someone had basically knocked my teeth back. My mouth was filling up with blood, so I jumped up and ran. I remember hearing someone laughing as I ran toward Market Street.

The first thing I encountered was a police car with police in it. I remember going up to them, spitting all this blood everywhere. My body was full of adrenaline, and I was still kind of processing what had even happened. So when I ran up to them, I was in a panicked state and talking very fast. Like, “Oh, my God. Help, help, help. Give me a ride to the hospital.”

But instead, they just looked at me, and the first words out of their mouths were, “We can’t touch you. We can’t put you in our car. We can’t take you anywhere because you might have AIDS.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867708/S_3.jpg)

Obviously, HIV and AIDS were very different than what they are now, because there wasn’t the medication and it was still kind of considered a death sentence. So their fear came from that place. But at the same time, they made this assumption just by looking at me. It was just so discriminatory and such a horrible thing. They didn’t even try to take a report. They did nothing.

At that moment, I felt less than a person. I can’t tell you how that feels. Like I did something wrong, like what happened to me was all my fault, and I didn’t deserve help. I was already feeling guilty for being dressed the way I was. They made me more ashamed. I mean, they could have easily been, like, “Oh, my God. You’ve been through a horrible thing. Just sit down, relax” — just treated me like a human being. But they didn’t.

I just remember walking away from them, and thinking, “Well, fuck you, I’ll take a cab.” Luckily, I found one, and the cab driver was nice enough to take me to the hospital even though I was bleeding all over the place.

When I got to the emergency room, I remember this older, nice doctor came up. He was the one who saw me, and he was like, “Well, what do we have here?” I was crying. I was hysterical. I told him what happened, and he gave me hope. I remember him saying, “You’re going to be okay. Luckily, there are no major injuries. You don’t have a concussion. There’s no internal bleeding in your brain.” He told me I’d need to see a dentist. But he made me feel safe. The next morning, my mom came and picked me up, and I had the teeth extracted.

After that experience, I developed a resentment toward law enforcement because they did absolutely nothing to help me. They did nothing to even say, “Who did this to you? Let’s go get him.” I mean, he was only two blocks down the road. They probably could have caught the guy. But they didn’t care — all they cared about was catching AIDS. I mean, how ignorant that they think you can even catch it like that.

I blamed myself for what happened for a long time. I really felt like there was something I did to deserve that, that it was my fault. For years, I never told anybody the truth about what happened. I said that it was a drug deal gone bad. I told my parents I got mugged. I had a different story for everybody. And I’m one of the lucky ones, in the sense that I walked away with my life.

Since then, I’ve had all kinds of different experiences with police. Once, the cops saved my life, so I’m not going to say the police are all terrible. The majority are probably dedicated to saving lives and helping people. But I think there’s certainly a faction that got into this job because they feel like they need power, and they’re just not good people. So it’s time to hold them accountable and to acknowledge that there’s a problem — to really ask, how can we protect our citizens?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867713/B_1_2_wide.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867714/B_3_4_wide.jpg)

Bonnie McIntosh

Now: 33

So, just to give you some backstory, I’m mixed, I come from a middle- to upper-middle-class family, and I grew up in a predominantly white neighborhood in a very nice suburb. When I was younger, I experienced microaggressions, like people touching my hair, and the occasional “ni**er” from a kid — which was obviously very frustrating and hurtful — but I didn’t fully realize I’d grown up in a bubble until I moved to LA.

I was about 19 or 20. I was standing outside of my apartment complex with my best friend, who is Jamaican and has extremely dark skin. We had probably gone to a party or something. We’re just talking and laughing — we’re a little loud, but we’re just a couple of kids standing outside my apartment.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867715/B_5.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21873815/bonnie_6_after_that_day.jpg)

And then, within minutes, four cop cars pull up with sirens blaring and completely surround us. A group of officers jump out of their cars, run past me to grab my friend, shove his face to the concrete, cuff him, and pull out two handguns. It happened so fast, I didn’t even realize what was going on. The officers never announced themselves. The only thing they said was, “On the ground” — after they were already on top of him.

It was my first time seeing a gun pointed at a person with the intent to kill that person. My friend was completely unable to move. He wasn’t in a situation where he couldn’t breathe, because I could hear him talking, but I was screaming at the top of my lungs, begging them not to kill him.

As they held him to the ground, two other officers came and, using force, took me down the street. They asked me if I was a sex worker and started questioning me as if I’d broken the law. I don’t really remember what the questions were because my mind was so focused on my friend. I just remember him trying to be as calm as possible. And I kept begging and pleading for them to let him go, but the cops would not stop questioning me.

I’m not sure exactly what happened, but after about 45 minutes, they let my friend go, and I just ran up to him. I hugged him. We asked the officers why they came, and they said that they had received a call that there were suspicious people on the street. That was it. “Suspicious people.”

We went into my apartment. I was a complete wreck, and my friend was shaken up but fine. When I asked him why, he explained to me that it was not his first time being held at gunpoint — that had happened when he was about 8 years old. He was used to it: This was the life of a Black man in America. But it was different for me. After that day, I never forgot the term “suspicious” — because what was suspicious about us? It was so clearly a racially motivated thing. We were in a neighborhood that was mostly Asian and white, so being Black was pretty much the only difference between us and everyone else that lived there.

A few months later, I was driving from Los Angeles to San Diego, and it was very late at night, probably 1 in the morning, and I needed gas. I was in San Juan Capistrano, which is an extremely white neighborhood, and I passed what I thought was an open gas station. I pulled in, went to the counter, and realized it was closed. I started walking back to my car and saw it was surrounded by cops.

They ended up cuffing me and searching my car without my consent. They claimed that they saw a beer can, but whatever. I had no drugs, no nothing. I hadn’t had a sip of alcohol, so they didn’t find anything. Then a male cop started body-searching me. I remember saying, “I will sue you. If you’re going to body-search me you have to bring in a female cop.” Eventually, he stopped.

They sat me down on the side of the road, and I could hear them talking about trying to book me for a DUI. I literally yelled out, “Just breathalyze me.” I knew if they did, there was no way they could book me for a DUI, and there would be a record of it. They refused and eventually let me go with a warning. All I could think was, What is the warning for? I didn’t do anything.

I remember sitting in my car crying for about an hour. I was on the phone with my father, and he was giving me the “Black dad talk,” where next time you need to get their badge numbers, never let a cop do this, ask their name, this is what you do when this happens, blah, blah, blah. And I was like, “Oh, I wish I knew this before. Why didn’t you tell me sooner?” He said he honestly didn’t think that I would deal with it. He thought I would be safe since I was light-skinned. Because I didn’t grow up in the hood or with police brutality.

These two experiences taught me the difference of privilege. The first taught me the privilege of being a light-skinned woman compared with a dark-skinned man. My friend and I were both doing the exact same thing. So why weren’t we both handcuffed? Why weren’t we both held at gunpoint? Why just him? But the second experience showed me that my privilege is fleeting — and just because I’m a light-skinned woman does not mean that I am exempt from being racially profiled, humiliated, and disrespected.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867730/M_1_2_wide.jpg)

Matthew Hooper

Now: 40

I was in high school and worked at the local skate shop. I didn’t make a lot of money, but I made my money — and I wanted to take my girlfriend on a date with the $80 that I’d just gotten paid for the week. I was walking on Riverside Drive, daydreaming, minding my own business, when the police pulled right up onto the sidewalk in front of me, blocking my path. I wasn’t doing anything, so I looked around to see if something else was happening around me that I didn’t notice.

Before I knew what was going on, I was slammed up against the wall. Even then, I thought it was a mistake. The officers didn’t bother figuring out my name or even calling me something respectful. Instead, they just called me “c***s****r” the whole time they were pushing me around.

So I am up against the wall, getting searched, and one of the officer’s hands goes into my pocket, and takes out the money I was just paid. When you’re 15, 16 — 80 bucks is a lot of money, so when I saw him take my $80 and put it in his own pocket, I said, “Hey man, you can’t do that. What’s your badge number?” At the time, I’d never had to deal with the police before, but I thought that it was a safe place to speak up. I was wrong. He covered his badge with his hand and he asked me, “What is my badge number?” in a sarcastic tone. My heart fell into my stomach. I felt nauseous and terrified.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21867733/M_3.jpg)

When I didn’t answer, he slapped me across the face and told me, “Get the fuck out of here,” which I did. I wasn’t going to try to stick around. I was fine giving up a week’s worth of pay to be safe.

I never went to my girlfriend’s house that day. I ended up going straight home, which was 16 miles away. I didn’t have any money, and I was too scared to jump the turnstile because I was terrified the police would harass me again, so I walked the whole way. It took me roughly four hours.

Just a couple years later, I started getting stopped all the time. It was September, October one year, and at that point, I think I’d already been stopped by police four times. Taken into the station three times, like a fish — catch and release, no charges. Then one day, my girlfriend at the time, who was a student at the School of Visual Arts, came to pick me up from work and walk with me to another job interview and hang out for the night.

After the interview, we met up with my friend and were walking around the city, reminiscing, chatting, enjoying the nice weather. As we were walking down an alley, three plainclothes police officers ran up to me, tackled me, and threw my friend and me to the ground. They kept us there for over 10 minutes, with a boot on my head and my face in broken glass. I have a little scar on my head from that now.

They took my girlfriend, who’s white, aside and kept questioning her; asking her how she knew us. Was she in trouble? They didn’t realize we were childhood friends, which is how we got to know each other and become boyfriend and girlfriend. But even when she said she knew me, it didn’t matter — they basically took me to jail because they thought I was pimping her.

All because I was dressed nice for my interview.

At the station, they paraded my girlfriend’s mother by my cell like I was in a zoo, which was embarrassing because I didn’t know her that well. After she left, I waited, but no one checked on me. It was Friday, and the courts were closed, so I had to spend the whole weekend in jail for something I didn’t do.

On Monday morning, they let me go, and all they said was, “We don’t have anything to stick you with, so you can leave.” No apology or nothing. About a week later, the same officers started coming into the restaurant I worked at during the lunch rush and asking me questions, bugging my manager, and harassing the owner. Basically embarrassing me in front of my bosses and the customers. The owner of the business was a really nice guy, so he gave me $1,000 and said, “Unfortunately, I can’t keep you working here. It’s destroying my business having these police here. So here’s some money. I wish you the best.”

It was then I decided: Fuck this place. I felt like NYC was no longer safe for me, and it was going to keep getting worse. I’m a mixed-race kid who grew up middle-class in Brooklyn. Before all this happened, I already had this feeling about how the world was — my dad had warned me — but I guess I didn’t take it at full stock that I wasn’t going to be treated the same way that my friends were, because a lot of my friends growing up were white. I’m a pretty big guy, and at a certain point, I thought, maybe I’ve become too large and I look too scary to a lot of people. Anyone who knows me knows I’m a jolly frickin’ teddy bear. But, being large, as many jams as it got me out of, I think it probably got me in just as many.

In my life, there were criminals who helped me, police officers who beat me. Police officers who helped me, criminals who swindled me. It’s all the same, just different gangs.

Kiana Moore is Vox Media’s vice president of content production and head of Epic Digital. She has a background in television and documentaries and believes in telling stories in an honest, human, and authentic way.

Nolwen Cifuentes is an independent photographer based in Los Angeles, California. She photographed Bonnie and Lynarion. Da’Shaunae Marisa is an independent photographer based in Cleveland, Ohio. She photographed Rabi and Rakim. Michael Starghill is an independent photographer based in Houston, Texas. He photographed Diamond.

CREDITS

Editor: Gina Mei

Highlight editor: Lavanya Ramanathan

Visuals editor: Kainaz Amaria

Designer: Will Staehle

Copy editors: Tanya Pai, Elizabeth Crane

Projects editor: Susannah Locke

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Kiana Moore

Read More