“You go to sleep in one world and wake in another.”

Poetry is a polarizing topic. Admit that you enjoy poetry and you’re likely to hear, “Oh, I don’t get poetry.”

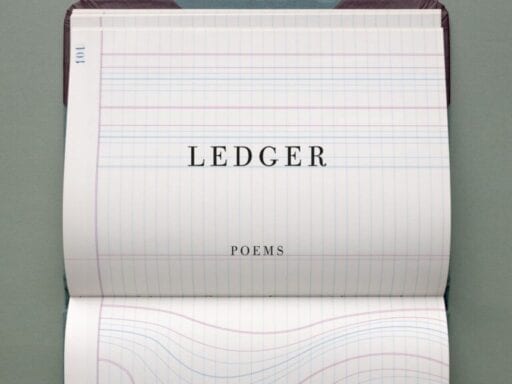

It doesn’t have to be this way. Granted, some poems are thorny, difficult tangles requiring significant work from the reader to comprehend. But some, like the ones in Jane Hirshfield’s new book, Ledger, are small gifts: morsels of meaning that slide right past your poetry defenses and lodge in your head.

Poets help you pay attention. They can look at something ordinary (a tree) and give you words to see it better, see it differently, appreciate it in a new way. Hirshfield has spent a long and award-filled career in poetry shining a light to show you, me, any reader something new about ourselves and the world we live in. Her poems are “tuned toward issues of consequence,” Ledger’s marketing copy proclaims, and I can find no better way to say it. She writes about what matters in the world.

I get it. You might not want that much light on a subject that can be hard to handle, especially in this stressful time. Death and climate change — even ants and flowers and relationships — are sometimes more comfortably left in the dark. It’s okay, Hirshfield understands. She doles out spoonfuls on her subjects (very few of the poems in the book are longer than a page, and most are written in short lines) and lets the reader swallow and breathe between helpings. And yet, as she said in an interview for the 2015 National Book Festival in Washington, DC, sometimes we need to “force ourselves past the common way of looking at things” to see a more nuanced view. That balance between merely showing you something and forcing you to see something in a new way is where Hirshfield lives.

It’s a measured approach, calm and contemplative. Hirshfield studied at California’s Zen Center; she is also an accomplished translator of Japanese poetry. You can feel this in the cadence of her work, and you can see it explicitly in her use of haiku-style stanzas in her longer poems (“9 Pebbles” is nine little poems in one).

Retrospective

No photograph or painting can hold it—

the stillness of water

just before it starts being ice.

Three-line haiku are among the simplest in appearance and the trickiest to write; you may have encountered them in school somewhere around the third grade, counting their syllables on your fingers. The Japanese haiku master Basho is the subject of Hirshfield’s 2011 ebook The Heart of Haiku, and Japanese influence can be felt in many of her poems. There it is in the distilled and concentrated form, there again in the series of poems that all begin with the same line, “Little soul.” It is especially apparent in the way Hirshfield’s poems treat the natural world as something marvelous and rare, something to be cared for and loved.

Word choice is key to the success of these poems

Jane Hirshfield thinks deeply about words.

Take the word that is the title poem: Ledger. A ledger, as the cover shows, is a book with lines on its pages, intended to help one keep track of, say, the influx and outflow of funds in an account. It’s a Google spreadsheet from before Google spreadsheets were a thing. rules and lines, everything in its place.

It is also a precipice — a ledge is — that the reader and the poet and the world are standing on, looking over the edge into a dark and unknowable abyss. We are all ledgers.

My favorite section in the book is a series of poems all beginning with “My”: “My Contentment,” “My Dignity,” “My Glasses,” you get the idea. Each poem is intensely personal since it follows that the poet is talking about “my” whatever it is, but each manages to also be about anybody. In “My Dignity,” Hirshfield writes of the possibility of aging and death:

My dignity, I know,

could be taken from me easily,

invisibly, in a single pickpocketed instant.

An errant driver. An errant rock. An errant anger.

Yet the words “aging” and “death” are nowhere to be found.

Here is “My Wonder” in its entirety:

That it is one-half degree centigrade.

That I eat honeydew melon

for breakfast.

That I look out through the oval window.

That I am able to look out through an oval window.

It’s cold out, yet there is melon for breakfast. That is a marvel of the modern world and deserving of wonder, but it’s not something you necessarily think about. But then there is “wonder” in “As If Hearing Heavy Furniture Moved on the Floor Above Us” (also in its entirety):

As things grow rarer, they enter the range of counting.

Remain this many Siberian tigers,

that many African elephants. Three hundred red-legged egrets.

We scrape from the world its tilt and meander of wonder

as if eating the last burned onions and carrots from a cast-iron pan.

Closing eyes to taste better the char of ordinary sweetness.

Again, you’re eating something sweet, but now you’re thinking about extinction. Yikes. This is what Hirshfield does so well: She gives you the observation of life as we’re all living it and the personal tragedy life entails, and then she slips in themes of planetary crisis. It’s the kind of gut punch good poems provide, the solid fist inside the velvet glove.

Ledger’s titular poem leads the sixth and final section of the book and draws the whole collection together. This ledger records some unusual quantities — the number of lines in a Pushkin novel, the height of an island — and concludes that measuring is both a human thing to do and not a terribly useful endeavor.

On this scale of one to ten, where is eleven?

Ask all you wish, no twenty-fifth hour will be given.

Measuring mounts—like some Western bar’s mounted elk head—

our cataloged vanishing unfinished heaven.

This is all the time we get in the world, says Hirshfield. Humans have written the world into their ledger, and for what? Her galloping syllables in the last line — no commas — at the end seem to propel us forward into the other poems in this concluding section, all of which deal in one way or another with what humans have done and are doing to the planet.

The facts were told not to speak

and were taken away.

The facts, surprised to be taken, were silent.

Poets can get away with all manner of legerdemain simply by performing frantic jazz hands and claiming, “I’m a poet! I follow my muse and cannot be held responsible for wherever it leads me.” Hirshfield is not that poet. She is responsible with every word choice, every line a deliberate beat, each poem its own chrysalis of meaning.

And lest these poems sound hard to grasp or not worth your time, I can assure you, they are a delight. Every other page I caught myself thinking, “Oh, I see what you did there, you clever thing,” as though the poet had stopped by for tea and was peering at me from over her cup. This is a book to read front to back, then at random, then front to back again.

Hirshfield’s poems are no less rich for being generally likable and accessible. You don’t have to love poetry to love these poems. There is no secret key required to unlock them. They speak and we all hear them loud and clear.

Author: Elizabeth Crane

Read More