“The inability of artificial intelligence to reproduce our smiles is teaching us something,” say the tool’s creators.

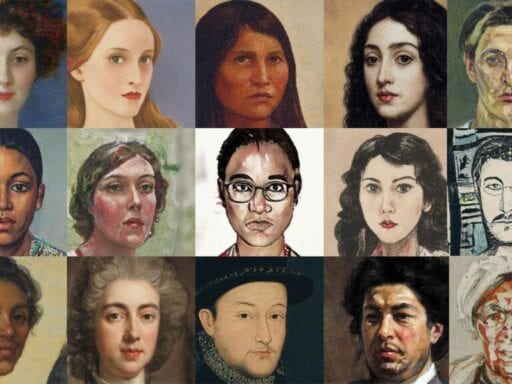

Researchers have launched a website that lets you upload a selfie and see it transformed into a classical portrait of you, thanks to artificial intelligence. Within seconds, you can become a van Gogh or Rembrandt or Titian painting. It’s pretty awesome, and I had way too much fun poking around the site.

That is, until it crashed Tuesday due to overwhelming traffic. The site, which makes art using an AI method known as a generative adversarial network, had gone viral. It’s easy to understand why: The fact that AI can make impressive art has already captured the public’s imagination (a machine-generated painting even sold for $432,500 at auction). Now that AI is making impressive art out of us, of course we’re going to be extra excited.

What I found compelling about AI Portraits was not just its ability to turn me into a fancy Renaissance lady (though, hey, I’ll take that) but also the rationale the researchers gave for creating the site in the first place. They want us to explore the way human bias creeps into AI — including the AI they’ve just placed at our fingertips.

Based at the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab, the researchers used 45,000 paintings to train their model. That data set includes portraits from the early Renaissance through to contemporary art, but its focus is on 15th-century Europe.

“This type of portraiture is quite distinctive of the Western artistic tradition,” they write on the site. “Training our models on a data set with such strong bias leads us to reflect on the importance of AI fairness.”

The researchers are drawing our attention to the fact that, yes, their AI tool remakes our selfies into beautiful portraits, but it’s one very particular type of beauty. It’s not recasting us in the style of, say, Indian miniature paintings, because it hasn’t been trained on Indian artwork. An AI trained on European art will churn out a portrait biased toward European styles.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18333189/Ai_art_spot.jpg) AI Portraits

AI PortraitsAnd it’ll be a portrait that doesn’t allow us to smile. As the creators explain:

We encourage you to experiment with the tool as a way of exploring the bias of the model. For example, try smiling or laughing in your input image. What do you see? Does the model produce an image without a smile or laugh? Portrait masters rarely paint smiling people because smiles and laughter were commonly associated with a more comic aspect of genre painting, and because the display of such an overt expression as smiling can seem to distort the face of the sitter. This inability of artificial intelligence to reproduce our smiles is teaching us something about the history of art.

It’s also illustrating the key AI principle of “bias in, bias out” — meaning that what you get out of an AI system really depends on what you feed into it. In other words, AI is not somehow “objective.”

That’s a reality many of us have not yet internalized, in large part because the makers and marketers of algorithmic decision-making systems have presented them as tools that can help us make choices more impartially.

The problem of algorithmic bias

By this point, we know this dream of unbiased AI is a fantasy, because we’ve seen example after example of how algorithmic bias damages people’s lives.

Amazon abandoned a recruiting algorithm after it was shown to favor men’s résumés over women’s. Researchers concluded an algorithm used in courtroom sentencing was more lenient to white people than to black people. A study found that mortgage algorithms discriminate against Latino and African American borrowers. Transgender Uber drivers had their accounts suspended because the company’s facial recognition system is bad at identifying the faces of people who are transitioning. Three other facial recognition systems were found to misidentify people of color much more often than white people.

I could go on, but you get the picture. It’s pretty bleak. So can we fix it?

The tech industry knows that human bias can seep into AI systems, and some companies, like IBM, are releasing “debiasing toolkits” to tackle the problem. These offer ways to scan for bias in AI systems — say, by examining the data they’re trained on — and adjust them so that they’re fairer.

But that technical debiasing is not the same thing as fairness. In some cases, it can result in even more social harm. For example, given that facial recognition tech is now used in police surveillance, which disproportionately targets people of color, maybe we don’t exactly want it to get great at identifying black people.

That’s why I’ve argued that we need new legal protections to safeguard us from biased AI, and drafted an algorithmic bill of rights with the help of 10 AI experts. The demands in it include transparency, consent, redress mechanisms, and independent oversight of algorithmic systems gone wrong.

Realistically, though, it may be a while before such protections become internalized by corporations, let alone enshrined in law. So in the meantime, I think it’s important for us to be fully aware of the risks posed by AI.

A fun website that transforms our selfies into cool paintings won’t get us all the way there, but precisely because it’s fun and cool, it can be a very effective educational tool.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Author: Sigal Samuel

Read More