Several creators have been called out for faking their age and their race.

A disturbing video is circulating on TikTok. It’s an explainer on a content creator who, it seems, posts nude photos of herself while digitally transforming her face to look younger — like, a teenager.

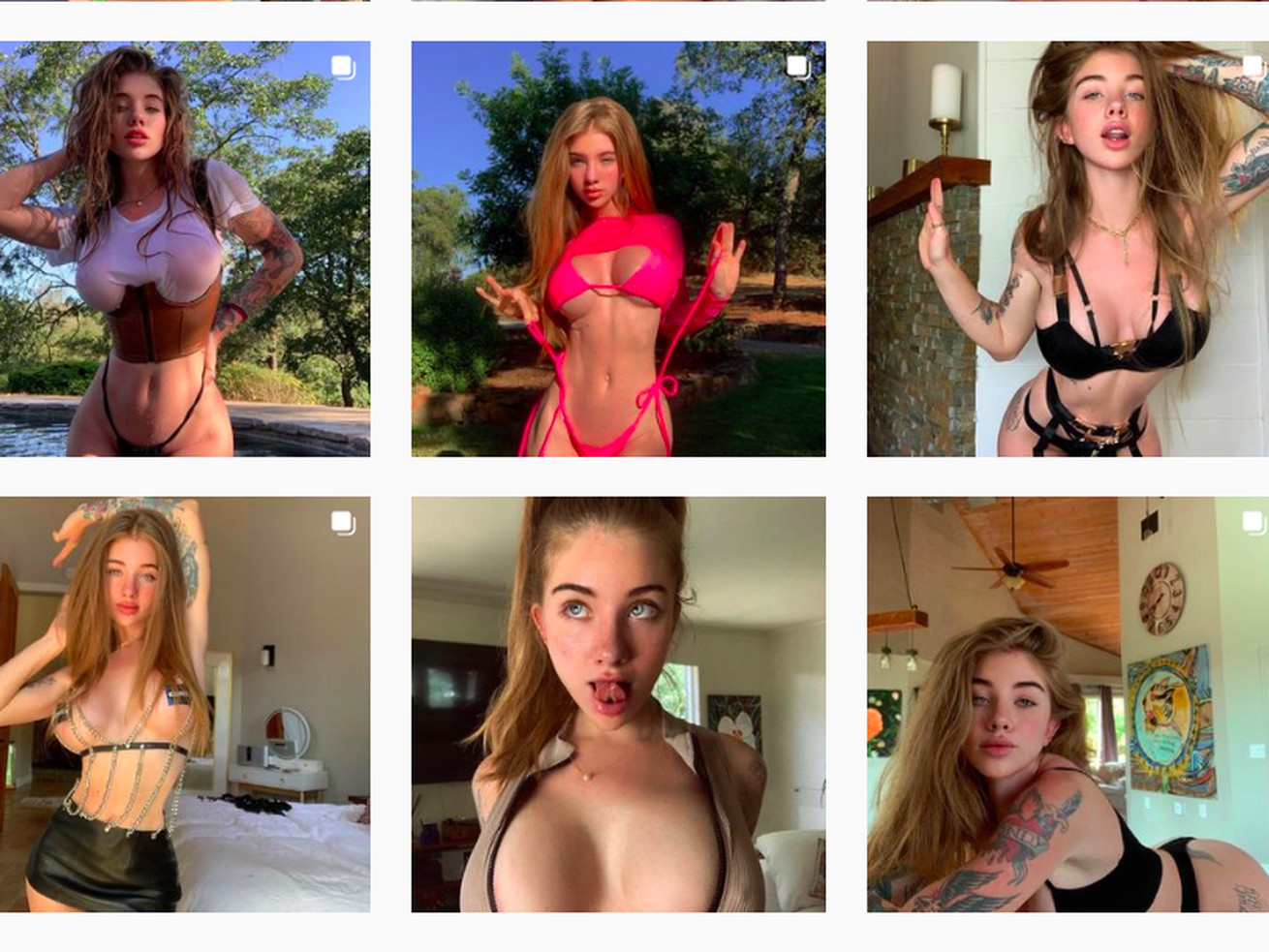

The case of “Diana Deets,” who goes by some iteration of the moniker “Coconut Kitty” on her social profiles, is not exactly difficult to solve. At first glance, nothing seems particularly odd: Her content is on the lewder end of the PG-13 content that’s always thrived on Instagram; she’s a young woman clad in the trappings of a typical bikini or lingerie model. A link in her bio goes to her website, where you can find a link to her OnlyFans account on which she promises “Yes, I get fully nude.” She has nearly 12,000 subscribers who pay $10.99 a month (you can do the math).

@bekahdayyy Creating fuel for p-words and profiting off of it doesn’t sit right with me. #AsSceneOnTubi #PrimeDayDealsDance #TubiTaughtMe #viral #fy #instagram

But if you scroll far enough back on her Instagram, you can see the slow transformation of an unmistakable adult into a rather uncanny-looking teen, despite most of the content — boobs, butts, a cascade of red hair — remaining the same. At a certain point, the line between “typical influencer FaceTune magic” and “actively impersonating a minor” appears to be crossed.

These boundaries are increasingly relevant when it comes to deconstructing online self-presentation writ large. Everyone who uses social media inherently portrays a certain version of themselves while omitting the rest; playacting is the essence of the internet, to the point where, one might argue, our ideas about truth and authenticity are meaningless, or at least grossly incapable of adequately describing what’s going on. Still, it’s become easier than ever to assume an almost entirely new identity online, without regard for the consequences such behavior can cause.

To reference a popular example, CGI influencer Lil Miquela was created by two digital artists to “create character-driven story worlds” on social media, which on its face sounds like an interesting artistic concept. Yet its real purpose appears to be far more banal: Adopt already popular markers of Gen Z cool kids and use it to rake in sponsorship money from fashion brands without having to deal with the messy realities of managing an actual person. In 2019, Lil Miquela’s creators released a vlog in which she — a digital avatar — claimed to have been sexually assaulted in a ride-share cab, after which many survivors criticized the team for using a very real problem in order to make their character seem more relatable.

CGI influencers are an extreme example of something far more common and insidious, however. Consider Blackfishing, a term that spiked in popularity around 2018, when conversations circulated around Ariana Grande, the Kardashians, and ordinary non-Black women who adopt the aesthetics of Blackness and capitalize on it. Over the past few years, the discourse around Asianfishing has grown more urgent as East Asian cultures have become increasingly visible in the US in entertainment and social media. The YouTuber Sherliza Moé recently made a video about the line between experimenting with trendy beauty looks — the “fox eye,” kawaii makeup, straight eyebrows — and perpetuating East Asian stereotypes, particularly when said trends are accompanied by clothing or mannerisms that accentuate one’s youth or submissiveness.

@slightlykiki happy aapi month … #aapiheritagemonth #aapi #racism #antiracism #culturalappropriation #asianfishing #korean #anime #stopaapihate

If you’ve been on TikTok, it’s possible you wouldn’t even have known you’d just seen someone Asianfishing. “A lot of people have asked me to talk about this girl, who is not Asian but frankly looks more Asian than I do,” begins @SlightlyKiki, a popular TikToker in a recent video. She’s referring to an account by the name of @itsnotdatsrs, who has nearly 2 million followers and posts videos of herself in skimpy schoolgirl cosplay and wears her makeup to mimic East Asian eye shapes. “You among so many others are literally training your millions of viewers to associate Asian women with sexualized children,” @SlightlyKiki says. “Non-Asians get to profit off this image of a sexualized little Asian girl, while actual Asian women suffer for it.”

@itsnotdatsrs is just one of dozens of white women who’ve been called out for capitalizing on harmful stereotypes by cosplaying Asianness. Last week, the writer Leo Kim wrote a piece on techno-Orientalism for Real Life magazine in which he dives into the bizarre world of internet communities that go to great lengths to not only appear, but “become,” Asian. Kim explains how the West has used the characterization of Asian bodies as “machine-like” to subjugate them. Yet in the 21st century, the idea of becoming a “machine” is now desirable. He writes:

As this techno-culture begins to celebrate a new, assembled view of self and explore its limits, the uncanny automata, the assembled human — the Asian body — becomes an ideal to aspire to rather than run from. Mainstream culture now celebrates artificially rendered influencers like Miquela, or figures like [pop star] Poppy who fashion their personas as robo-entertainers … These figures — with their pushed and pulled faces, edited eyes, skin so airbrushed it looks like a render — are uncanny not by accident, but by design. The otherness of the Asian body, which is racialized as technological, is simulated through technology.

I’m reminded of the panic a few years ago over what would happen when the ability to create convincing deepfakes — digitally created likenesses of actual people — would become widespread. We were warned that videos showing, say, Nancy Pelosi supposedly admitting she’d rigged the ballots in the 2020 election could go viral and start a deadly riot (although clearly nobody needed a deepfake to do that). We were warned that, should everyone on the internet have access to appearance-altering software, it would incite catastrophic political chaos.

But that hasn’t been the biggest threat of deepfakes thus far. Instead, what they’ve wrought is more harm to the people society already marginalizes: women, whose likenesses have been weaponized as revenge porn and have suffered severe consequences, and people of color, where anyone from a Twitter troll to an Instagram influencer can adopt the aesthetics of Blackness or Asianness to whatever end they please. Meanwhile, they can weave in and out of those identities at will without experiencing the discrimination and systemic barriers that come with living as a Black or Asian person.

When an eerily accurate deepfake version of Tom Cruise went viral on TikTok earlier this year, its creator said he was trying to prove a point: that actually, it’s really, really hard to convince people that a deepfake of a celebrity or politician is authentic. “You can’t do it by just pressing a button,” he told The Verge. The problem is that everybody knows what Tom Cruise looks like. You don’t have to be a talented digital artist in order to make yourself look decades younger than you are, or to make yourself look like a different race. You literally can do it just by pressing a button.

Underneath all this ickiness, there is another, possibly more disturbing element, which is that Coconut Kitty was right: More people did want to look at her when she made herself look like a teenager, because of course they did, because teen girls are so highly fetishized, as are Black and Asian women. Tech companies like Instagram, Snapchat, FaceTune, and the makers of FaceApp exploit this by giving us innumerable sophisticated tools to convincingly warp our identities. Using these apps is a trap that bleeds into the real world in predictable ways: more young people opting for plastic surgery to make their faces look more like they do with a filter, and at least one white influencer who got surgery in order to reflect the fact that they “identify as Korean.”

All of this, ultimately, is an aftereffect of existing within an image-centric culture in mostly lawless digital spaces. But as Kim argues in his piece, “In the end though, it starts and ends with our bodies.” The promise of the internet was that we could be anyone we want. What did we expect?

This column first published in The Goods newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one, plus get newsletter exclusives.

Author: Rebecca Jennings

Read More