And the rest of the week’s best writing on books and related subjects.

Welcome to Vox’s weekly book link roundup, a curated selection of the internet’s best writing on books and related subjects. Here’s the best the web has to offer for the week of January 26, 2020.

- A new survey shows that publishing has failed to become significantly more diverse since 2015, Publishers Weekly reports.

- On the heels of that survey and the ongoing American Dirt controversy, at Refinery 29, Patrice Caldwell, founder of People of Color in Publishing, talks through some of the problems in publishing that can ensue:

Simply put, the very senior publishing professionals who have power to truly change this industry for the better are the same people who are making things worse, again and again. In 2017, Keira Drake pushed back her debut, The Continent, because it faced criticism about racist character portrayals. But what most don’t know is that the same editor that acquired that book also acquired The Black Witch, another YA novel that received similar criticism. There are many more patterns like this.

- Meanwhile, at the Atlantic, Hannah Giorgis considers American Dirt and the limits of polemical fiction:

Are the tens of thousands of migrant children held in government custody, some of whom never see their families again, to feel comforted by American Dirt’s limp exhortation to the average reader—or by Oprah Winfrey’s selection of the novel for her famed Book Club? For those whose lives are not shaped fundamentally by the indifference of others, empathy can be a seductive, self-aggrandizing goal. It demands little of author and reader alike. “The empathy model of art can bleed too easily into the relishing of suffering by those who are safe from it,” the author Namwali Serpell wrote last year in an essay for The New York Review of Books. “It’s an emotional palliative that distracts us from real inequities, on the page and on screen, to say nothing of our actual lives. And it has imposed upon readers and viewers the idea that they can and ought to use art to inhabit others, especially the marginalized.”

- The other big publishing controversy over the past few weeks has been the short story “I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter,” a piece by the trans writer Isobel Fall that deconstructed the title meme through the lens of cyberpunk. Fall took down the story after enormous backlash, and at the Outline, Gretchen Felker-Martin argues that this decision was a mistake:

Many reactions to Fall’s story, for all that they come from nominal progressives, fit neatly into a Puritanical mold, attacking it as hateful toward transness, fundamentally evil for depicting a trans person committing murder, or else as material that right-wing trolls could potentially use to smear trans people as ridiculous. Each analysis positioned the author as at best thoughtless and at worst hateful, while her attackers are cast as righteous; in such a way of thinking, art is not a sensual or aesthetic experience but a strictly moral one, its every instance either fundamentally good or evil. This provides aggrieved parties an opportunity to feel righteousness in attacking transgressive art, positioning themselves as protectors of imagined innocents or of ideals under attack.

- Stephen Joyce, the executor of James Joyce’s literary estate since the 1970s, died last week. Also at the Outline, B.D. McClay writes in praise of Stephen and the dying breed of obstinate literary executors:

I like James Joyce’s letters to Nora — indeed, I find them sweet — but they were not written by my grandparents. I don’t think it’s wrong to go snooping around in a dead writer’s diaries and letters, but most of them would be horrified to know their private thoughts and correspondence were published and went out of their way to try to prevent such things from surviving their death. That their families take this desire seriously does not seem, at least to me, a reasonable thing anyone can resent them for. James Joyce’s work might be public property, but when it comes to letters, at least as far as this voyeur is concerned, you can hardly get mad at someone for closing the blinds.

- At Slate, Dan Kois demands that some American publisher acquire the US rights to a fantasy novel from New Zealand and, solely on the strength of Kois’s summary, I would like to add my pleas to his:

When I was finished with The Absolute Book I wanted everyone I knew to read it so I could discuss it with them. I’ll have to be satisfied, for now, with using the tried-and-tested form of a semi-deranged blog post to attempt to browbeat American publishers into acquiring it. The fact that the only way for most Slate readers to read this majestic, brain-bending novel is to pay international shipping from a bookstore in New Zealand is maddening, but it’s an opportunity as well—for any clever American publisher who wants to make a bunch of money while publishing something truly remarkable. I hope someone leaps at the chance.

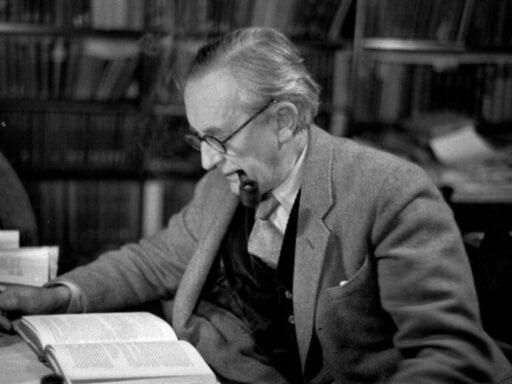

- At LitHub, John M. Bowers looks at how Tolkien’s procrastinating on his academic work on Chaucer drove him to write The Lord of the Rings:

For so many years, in short, he had been loafing in his scholarly career as a losel who squandered time on children’s stories when he should have been whipping his Beowulf book into shape. He confided to his publisher in 1937 that Oxford would merely add The Hobbit to his “long list of never-never procrastinations” (Letters, 18). Fiction-writing simply did not count in terms of academic production, especially after Tolkien had idled away his two-year Leverhulme Research Fellowship. “The authorities of the university,” he would lament when The Lord of the Rings was in press, “might well consider it an aberration of an elderly professor of philology to write and publish fairy stories and romances” (Letters, 219).

- A new research firm has begun programming an AI to write poetry, reports LitHub. Here’s the computer’s take on Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18.” The bolded lines are from Shakespeare (uses rhyme and meter, human, boring) and the rest is pure robot genius, baby:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

And the grass is green and the trees are full of fruit’.

And, when the sky is blue and the heat is blazing,

And the rain is falling upon the fields and the trees,

But the sun is downcast as when it is rising,

And the sky is covered with clouds and the land is shrouded by fog,

And the sky is not bright to behold yet:

Thou hast not a thousand days to tell me thou art beautiful.

- At the Cut, Nora Caplan-Bricker sits down with Vivian Gornick, the hugely influential but largely forgotten feminist culture critic:

Though she deserves as much credit as any writer alive for codifying the current form of the personal essay — The Paris Review has credited her with pioneering the genre of “personal criticism” now associated with essayists such as Leslie Jamison, Maggie Nelson, and Jia Tolentino — her influence as a writer has always outstripped her exposure. Other authors have long valued her writing about writing — its unyielding frustrations and the battle for selfhood it encompasses. Perhaps most beloved among her 12 books are a pair of memoirs: Fierce Attachments, from 1987, and The Odd Woman and the City, from 2015, both of which consider her struggle to forge an unconventional life. A 13th book, Unfinished Business, a reflection on rereading done in her signature hybrid of memoir and criticism, comes out in February. Over the years, a certain romance has accrued to the person of Gornick herself, a born-and-bred New Yorker, radical second-wave feminist, and archetypal staffer for the late, great downtown alt-weekly The Village Voice. Though she says she has always felt like an outsider in literary circles, her work sits at the heart of an alternative canon in which art grows from the politics of being oneself.

- So Nancy Drew turned 90 this month, and Dynamite comics is celebrating … by killing Nancy off so the Hardy Boys can solve her murder. Polygon has the story.

And here’s the week in books at Vox:

- The controversy over the new immigration novel American Dirt, explained

- Oprah says she wants to hear “both sides” of the American Dirt debate on appropriation

- American Dirt’s publisher cancels the rest of the book’s tour, citing threats

- What is going on with America’s boys?

As always, you can keep up with all our books coverage by visiting vox.com/books. Happy reading!

Author: Constance Grady

Read More