There There is a searing examination of American Indianness in the 21st century

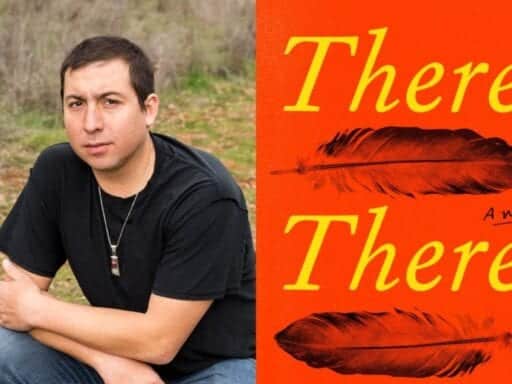

If there’s a novel of the summer this year, it’s Tommy Orange’s There There.

“Have you read There There yet?” I was asked at a publishing party.

I confessed that I had not.

“So she’s not there there yet,” one of the publishers concluded. “But I’m there there.”

“Is it that good?” another one asked.

“It’s so good,” the first confirmed.

“Yes, Tommy Orange’s New Novel Really Is That Good,” says the New York Times headline, in an echo of its famous Hamilton review.

Reader, I must confirm: There There really is an extremely good book.

There There is a novel about American Indians in Oakland, California: “Urban Indians,” Orange writes, who “came to know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range, the redwoods in the Oakland hills better than any other deep wild forest.”

Orange takes on the voice of a different character in each chapter. And his characters dance in and out of one another’s lives with relationships so complex you’ll want to chart them — Edwin from chapter four is working with Blue from chapter 17 who is the daughter of Jaquie from chapter 10 who is the sister of Opal from chapter three — but all of them converge at a single point: the upcoming Oakland powwow.

For everyone involved, the powwow is a shifty, ambivalent avatar of Indianness, an identity that many of these characters feel themselves to be playing at. In 21st-century America, the concept of “Indian” is so often treated as an anachronism (a reminder of a people tragically slaughtered, with remnants of the population on reservations) rather than as an identity held by living human beings, that it’s difficult for Orange’s characters to find a way to think of themselves as authentic Indians.

“I’m as Native as Obama is black,” says Edwin, who has a white mother and grew up without meeting his American Indian father. “It’s different though. For Natives. I know. I don’t know how to be. Every possible way I think that it might look for me to say I’m Native seems wrong.”

Orvil, meanwhile, is American Indian on both sides but grew up without learning about this heritage, so he gets it all from YouTube. When he puts on tribal regalia and looks at the mirror, he appears to himself as “dressed up like an Indian.” That’s the only way that he knows to be Indian, writes Orange: “It’s important that he dress like an Indian, dance like an Indian, even if it is an act, even if he feels like a fraud the whole time, because the only way to be Indian in this world is to look and act like an Indian. To be or not to be Indian depends on it.”

As Orange’s characters attempt to reconcile themselves to their shifting sense of their identities, tragedy lurks in the background. At the opening of the novel we met Tony, a kid with fetal alcohol syndrome (he calls it the Drome) who’s mixed up with some petty criminals, a gun, and plans for a robbery at the powwow. You know that as soon as everyone finally gets there — to the place where they are supposed to be truly and authentically Indian, as best they can figure out what it means — something terrible is going to happen.

Orange’s crisp, elegant sentences keep things moving unobtrusively, but his greatest strength is his ability to mimic the rhythms of speech without becoming so gimmicky as to be grating. Each character in this novel has a distinct narrative voice, but there’s a unified flow from chapter to chapter; it can sweep you along.

This is a trim and powerful book, a careful exploration of identity and meaning in a world that makes it hard to define either. Go ahead and go there there.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png