Nearly 1 in 5 election officials say they’ve been threatened because of their job.

In a speech on voting rights delivered on Friday, Attorney General Merrick Garland warned that “the dramatic increase in menacing and violent threats against all manner of state and local election workers” is a threat to the country’s democracy.

Garland is right to be concerned. A new survey released by the Brennan Center for Justice found that 17 percent of local election officials in the United States have faced threats because of their job. The same survey, which was released alongside a larger report by Brennan and the Bipartisan Policy Center on threats to America’s elections, found that nearly a third of these officials — 32 percent — have “felt unsafe because of [their] job as a local election official.”

The survey was conducted by Benenson Strategy Group, and it included interviews with 233 election officials “from across the country.”

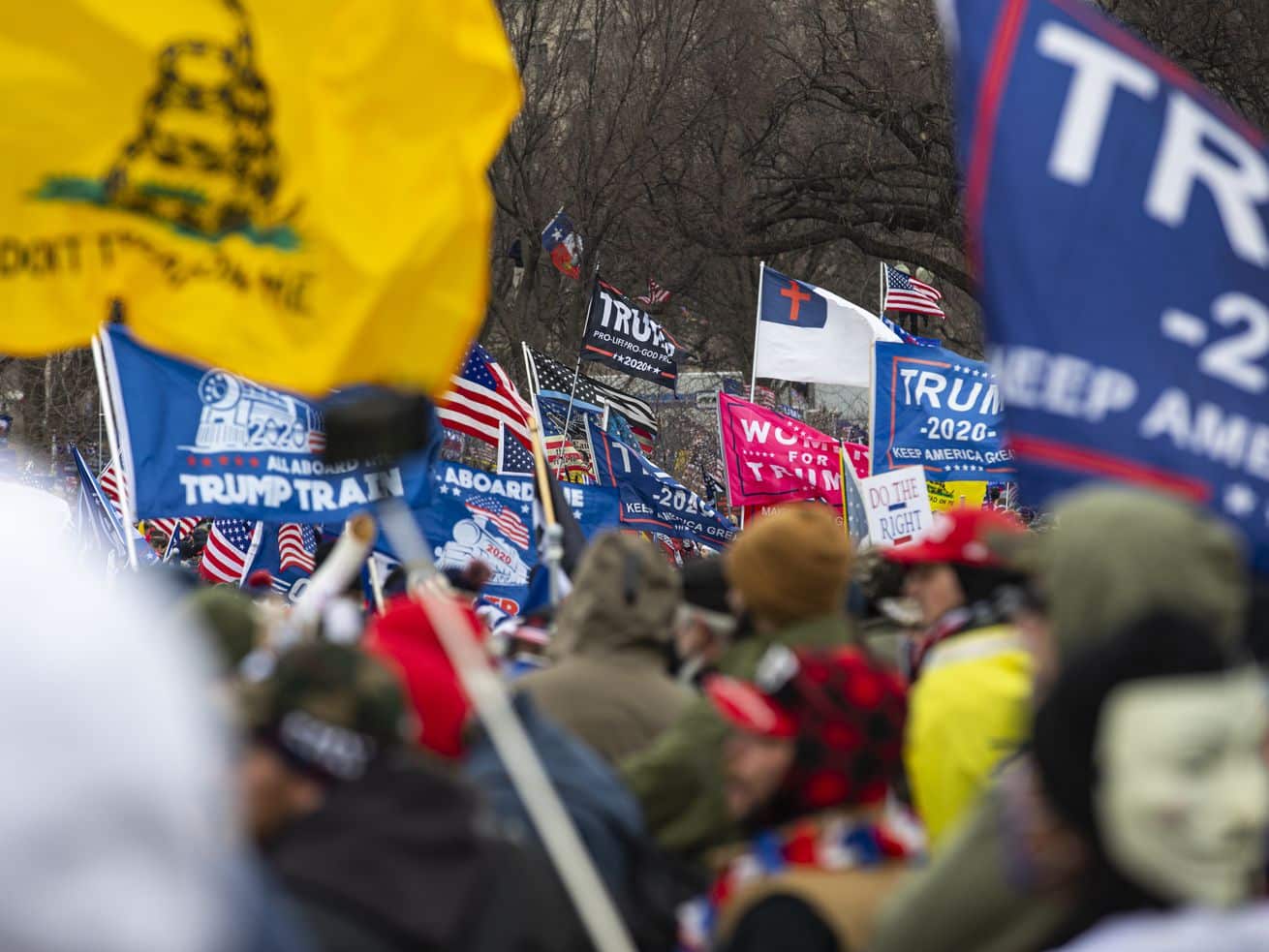

The Brennan Center’s survey quantifies a phenomenon that appears to have emerged from former President Donald Trump’s conduct during the 2020 election, and his subsequent defeat in that election. Just hours before Garland pledged to prosecute individuals who target election officials in that same speech, Reuters published a long article cataloging some of the threats faced by election administrators and their families.

One of the primary targets of these threats is the Raffensperger family, whose patriarch, Brad, is Georgia’s Republican secretary of state. After Trump lost the state of Georgia last November, the outgoing president tried unsuccessfully to pressure Mr. Raffensperger to overturn that result — Trump even told Raffensperger that he wanted the Georgia official to “find 11,780 votes” for Trump in a phone conversation that was recorded and made public by the Washington Post.

President Joe Biden defeated Trump by 11,779 votes in Georgia.

As Reuters reported, even before this phone call occurred, however, the Raffensperger family started receiving death threats in an apparent effort to intimidate Mr. Raffensperger into either resigning or attempting to flip the election to Trump. Tricia, Brad’s wife, was bombarded with abusive texts — one from someone impersonating her husband, which read “I married a sickening whore. I wish you were dead.” Others explicitly threatened to murder the entire family.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22659063/temp.jpg) Reuters

ReutersNor are these sorts of attacks limited to high-ranking officials such as Georgia’s top elections officer. Vanessa Montgomery, a Black army veteran who was a polling official for the small town of Taylorsville, Georgia, was reportedly chased by an SUV that attempted to run her and her daughter off the road while they were delivering ballots to an election office.

They escaped after calling 911, and eventually met up with police officers who escorted them to the office.

Similarly, the Brennan/Bipartisan Policy Center report also lays out several examples of terroristic threats against election workers, and that proposes some policy solutions.

The wife of Al Schmidt, a Republican commissioner in Philadelphia, received death threats saying things like “ALBERT RINO SCHMIDT WILL BE FATALLY SHOT” and “HEADS ON SPIKES. TREASONOUS SCHMIDTS,” and Schmidt and his family eventually were given a 24-hour security detail. Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, received similar protection after a man called her office asking “what she is wearing so she’ll be easy to get.”

These threats, and other attacks on election administrators, appear to be taking a toll. While some retirements are normal after a presidential election, about a third of Pennsylvania’s county-level election officials quit in the last 18 months. According to the Associated Press, about two dozen county and municipal clerks in Wisconsin, who oversee elections in their communities, retired since last November’s election.

At the very least, this means that these jobs will be filled with people who are less experienced and thus less likely to run smooth elections. Threats against election officials are likely to discourage the best candidates from applying for these newly vacant jobs. And, in the worst-case scenario, these jobs may be filled by conspiracy theorists who share the same ideology as the people making threats against incumbent officials.

Democracy depends on election administrators who will run fair and impartial elections. And at least some of Trump’s most rabid supporters appear eager to make officials who believe in such impartiality suffer.

Four interlocking threats to democracy

The Brennan/Bipartisan Policy Center report lays out four dangers facing election administration in the United States. It’s a broad list, which captures large swaths of the problems facing American democracy generally. Nevertheless, these four categories are useful because they highlight how each of the problems identified by the report tend to make the others worse.

The first category is the “alarming level” of violent threats against election officials beginning in 2020.

The second danger is the spread of disinformation surrounding the election, a problem that was exacerbated by the rise of social media. 2020 was hardly the first election year when politicians, media figures, or rank-and-file partisans spread falsehoods, but social media enables disinformation to spread more broadly among partisans who are eager to hear such false information — including “lies about election processes to try to influence election outcomes.” According to the Brennan Center’s survey, 78 percent of election officials “said that social media, where mis- and disinformation about elections both took root and spread, has made their job more difficult.” And “54 percent said they believe that it has made their jobs more dangerous.”

The third is attempts by elected officials themselves to influence election administration for partisan gain. This category includes tactics like Trump’s “find 11,780 votes” call to Secretary Raffensperger or Arizona’s GOP-led “audit” of the 2020 election, where Republicans are apparently hunting for evidence of bamboo fibers in ballots to claim that China tampered with that election.

This third category also includes legal attacks on free and fair elections, such as a Georgia law that would allow Republican officials to take over local election boards that have the power to shut down polling precincts and disqualify voters.

Finally, American elections are vulnerable because work conditions for local election officials were often terrible even before these officials started receiving death threats. According to the Brennan/Bipartisan Policy Center report, “election officials must be experts in logistics, cybersecurity, communications, information technology, customer service, and voting law.” But they are often paid dismal salaries for such a demanding job.

The average salary for a local election official is $50,000, according to the report. And this salary can be much lower in smaller jurisdictions. Nearly half of officials from areas with 5,000 or fewer registered voters are paid less than $35,000 a year — and a quarter earn less than $20,000.

These four problems tend to exacerbate each other. As disinformation spreads on social media, individuals who are prone to conspiratorial thinking and violent behavior are more likely to see it and threaten election officials. Threats from individuals and elected officials discourage incumbent election administrators from remaining in their jobs. And, as jobs become vacant, good candidates are unlikely to apply for a highly demanding job that pays poorly.

There are solutions to these problems, but it’s not clear people in charge want to solve them

The Brennan/Bipartisan Policy Center report also includes a wide range of proposed solutions to these four problems. States, for example, could provide security protection directly to officials who are threatened. They could help election officials pay for security systems in their homes. And they could work with election workers to remove their personal information from databases that can be used to dox them.

Beyond paying higher salaries to local election officials, states could also hire state-level employees with expertise in subjects like “communications, cybersecurity, logistics, information technology, and law,” who can guide local officials on how to run secure and efficient elections, and how to comply with their legal obligations.

Social media companies, meanwhile, can take steps like identifying users who chronically spread false information online, and delaying publication of these users’ content until the company has a chance to review it for violations of the company’s terms of service.

But to really fix problems like intimidation of election officials or disinformation, we need cooperation by companies that are not directly accountable to the public — or by elected officials who are happy to tear down democracy so long as their party benefits.

If Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg or Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey don’t do enough to stop disinformation from spreading online, it’s not like they can be voted out of office and replaced with a different CEO.

At the state level, there are some examples of Republicans taking their obligation to protect elections and election officials seriously. After Arizona’s Secretary Hobbs received death threats, for example, Republican Gov. Doug Ducey’s office ordered state troopers to provide her with a security detail.

But the sort of state lawmakers who would enact Georgia’s voter suppression law or who would conduct a months-long goose chase hunting for bamboo fibers in Arizona ballots are unlikely to take steps that will ensure fair and impartial elections. When you are the problem, you can’t be the solution.

Congress, meanwhile, could step into the breach — the Constitution gives Congress broad authority to determine the “times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives.” But that would require the United States to have a functioning legislative branch.

For the moment, at least, voting rights legislation of all kinds is stalled in the Senate. In part, that’s because a handful of Democratic senators insist on preserving a filibuster rule that allows Republicans to veto legislation. And with Democrats holding the narrowest possible majority in the Senate, every single one of them would have to agree to a voting rights bill even if the filibuster were abolished.

This isn’t to say that nothing will be done. Garland did promise prosecutions against individuals who threaten election officials. Facebook and Twitter did ban Donald Trump from their platforms, at least for now. Many states have governors and state legislatures that believe in democracy and want to preserve it.

But, ultimately, it’s very hard to preserve democracy when one of a nation’s two major political parties is turning against it.

Author: Ian Millhiser

Read More