Should I get it? And, if I do, am I taking a dose from someone who needs it more?

The big Covid topic on everyone’s minds is boosters.

On Friday morning, the FDA authorized Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna booster shots for all adults ages 18 and up. And later in the day, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) followed suit.

The CDC said that every adult who is at least six months removed from their second shot of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine can get a third shot. And it recommended that people over the age of 50 or in long-term care settings make sure they do so.

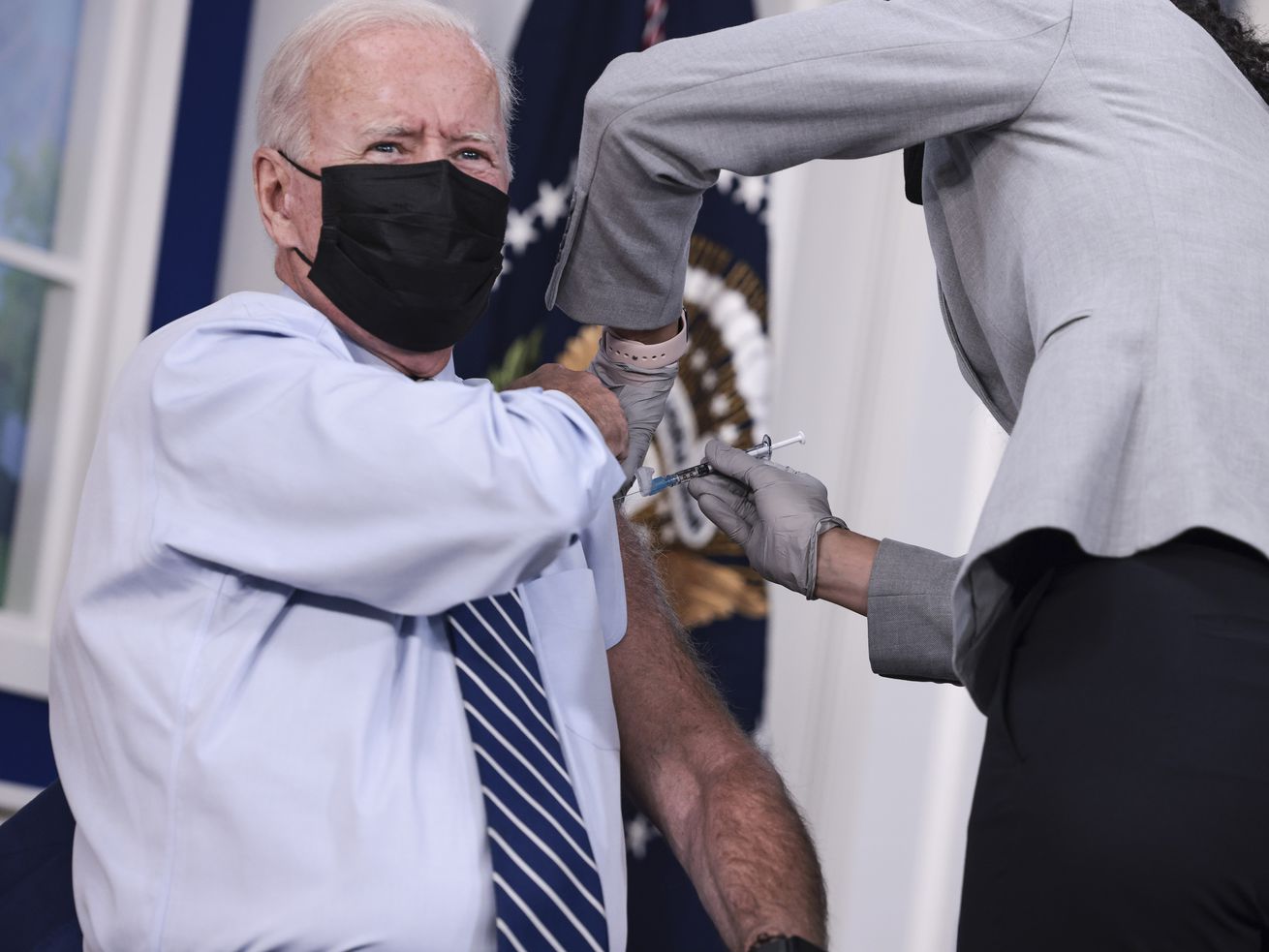

The long-awaited decision comes after months in which the boundaries of who can get a booster have been widening. The Biden administration first announced its plans to make boosters widely available in August. Since then, we’ve seen the rollout of boosters to Pfizer and Moderna recipients over age 65, and those who are 18 or older who are immunocompromised or at high risk of infection. All adult Johnson & Johnson one-dose recipients have also been approved for booster shots, two months after their first.

The fact is, the federal government has been lagging on this front. Several states have already gotten ahead of the federal government by approving boosters for adults: Colorado, California, New Mexico, and Arkansas, among others, have all moved in the last few weeks to declare nearly all adults eligible. And based on anecdotal accounts, even adults not eligible yet have been able to get a booster shot.

That has left people anticipating official federal guidance that anyone who wants a booster can get one — and it has also fostered confusion over what exactly the US’s public health game plan is, and whether getting the booster is the right personal choice for any given person.

Those questions will only loom larger now, with the expanded booster eligibility. Here’s how to help you think through the situation.

I’m healthy and not at higher risk for serious disease. Should I get a booster?

Personally, this describes my situation — and I’m getting one.

If you got two shots of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines, as I did, you’re already fairly well-protected from severe Covid-19 outcomes. The main thing a booster does is make you less likely to get infected and (mildly) sick — but that’s still good to have.

We have a lot more data on these vaccines than we did when they were first approved. We know that they generally remain very effective against severe illness and death even a year after someone gets two shots. But they do wane in effectiveness against infection. Six months after your second dose, the vaccine is less protective against catching Covid-19 and, perhaps, virus spread.

That’s because antibody levels in the blood decline over time. Experts disagree on how much people should worry about that. Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told me that a healthy, functioning immune system gradually prunes blood antibodies for infections the body hasn’t encountered, and it doesn’t mean you won’t fight off Covid-19 just fine (likely suffering only mild, maybe even unnoticeable illness, if you do catch it).

There’s a fair debate to be had about whether preventing infection, if illness is likely to be mild, is all that important as a public health priority. But even though I won’t get all that sick if I get Covid-19 because I’m fully vaccinated, I prefer not to get it at all. The booster does reduce my risk of becoming infected with Covid-19 — period. For me, that’s sufficient to take a booster, especially given that I didn’t have bothersome side effects from the first two shots.

This lukewarm recommendation becomes a much stronger one for older adults and others at elevated risk from Covid-19 due to their health or setting. If your immune system functions less well, then at least one additional shot might be needed just to get your immune system to the level of readiness that other people were at after two shots. That’s well worth it.

And if you got Johnson & Johnson, you should definitely get a booster (which the CDC had already approved) to combat some waning in vaccine efficacy for the one-dose shot.

If I’m healthy and get a booster, am I taking a dose away from someone who needs it more?

A lot of Covid-19 questions are complicated, but here’s one thing we can be fairly sure of: Your booster shot, if you choose to get one, is very likely not directly coming at the expense of other people, experts told me.

The concern stems from the fact that many people in the US will be getting their third shot when about half of the world hasn’t had even one shot. That’s not just an injustice and a humanitarian wrong, it’s also strategically foolish: Virus variants can develop more easily when Covid-19 cases are high, and vaccines are the most effective way to lower them.

If skipping a booster would get that shot to someone in a poor country instead, I’d prefer to do that.

But that’s not really how vaccine allocation works. Many months ago, the US placed orders with Moderna and Pfizer for millions of doses of their vaccines. Other countries and international organizations did the same.

Those orders, experts told me, are being fulfilled in the order they were placed — so if Moderna is committed to delivering 20 million doses to the US first, then 10 million to France next, that’s the order they will send them. And if the US orders additional doses now in response to increased demand from booster-getters like us, that request will be at the back of the queue.

Not getting your booster won’t get that shot to people in other countries who need them more. What might help, Amanda Glassman, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, told me, is queue-swapping: the US formally ceding its place in line to other countries that need it more or to Covax, the international alliance to vaccinate the world.

Unicef has called on the US and other rich countries to do just that. The US also could — and should — donate excess doses (it has donated roughly 200 million of them so far), but it’s unclear how demand for boosters this fall and winter will affect the odds of new donations of excess doses in the future; the US plans to fulfill its remaining unfulfilled pledges of donating more than a billion doses through purchase orders for Covax currently in the queue.

If you’re frustrated, like I am, that millions of vaccines are going unused in the US while they’re badly needed elsewhere, you should absolutely push for the US to give up its place in line. But skipping a booster shot won’t change how many doses Moderna or Pfizer will deliver to the US before they move on to the next country on their list.

And within the US, we have plenty of supply of mRNA vaccines at this point — so getting a booster isn’t taking one from your neighbors either.

Why there has been so much confusion over boosters

The confusion surrounding boosters is in some ways an outgrowth of messy communications from the public health establishment. It likely explains the markedly different response to boosters than to the initial wave of vaccines.

Conversations about boosters have been tinged with ambivalence and uncertainty. In the early days when the vaccines first started rolling out to the larger population, my family and friends drove for hours to land our Covid-19 vaccines. I hate long car rides, but I spent the whole time actively excited. There’s a bit less of that feeling this time (but don’t tell that to our 5-year-old, who was so inspired she declared she’ll invent an immortality shot when she grows up).

“We’ve miscommunicated this,” Offit told me. He argues that the adults dying of Covid-19 are almost all people who are unvaccinated or those at much-elevated risk, and the back-and-forth on boosters for healthy people has ended up leaving people confused. Many people who are already very safe from serious infection or death have ended up with the impression they’re at risk, while people who actually are at risk — largely those who are unvaccinated — have ended up with the impression the vaccines don’t really help.

And after a year in which much messaging emphasized resource scarcity — that we shouldn’t wear N-95 masks lest we take them from doctors and nurses, that we shouldn’t skip our place in the initial vaccine line lest we get a vaccine someone else needed more — there’s been little effort to answer people who wonder, reasonably, if getting a booster takes one from someone who needs it more.

The FDA and CDC announcements on expanding booster eligibility should hopefully clarify some of the confusion out there. And the science on booster shots will continue to evolve — as we learn more, it should inform our public policies and individual decision-making.

In the meantime, it’s okay to go ahead and grab a booster to increase your protection. The earlier doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are still protective against severe disease and hospitalization, but an added coat of armor — especially since there is little vaccine scarcity in the US — can only help.

Update, November 19, 6:15 pm: This story was updated to reflect news of the CDC approving expanded booster shot eligibility, after FDA approval earlier in the day.

Author: Kelsey Piper

Read More