Trump’s refugee policy helps Christians from the former Soviet Union, and hurts everyone else.

The Trump administration has slammed the brakes on bringing refugees to the US. At the end of its first full fiscal year, new government data shows, the administration is falling way short of the expectations it set for resettling refugees — which were, themselves, way lower than the levels set by President Obama and his predecessors.

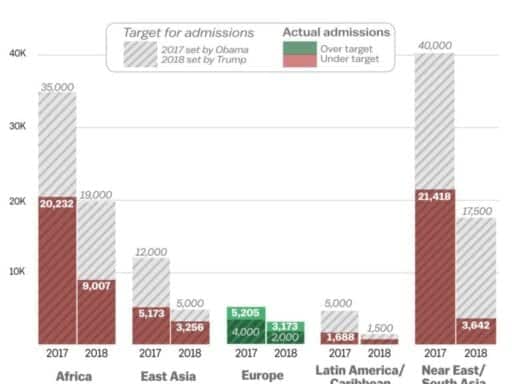

While refugee arrivals from other parts of the world are down as much as 90 percent from Obama-era levels, resettlements from Europe — specifically, the former Soviet Union — have taken only a modest hit. In the rest of the world, the Trump administration isn’t going to come anywhere close to the “ceilings” it set for the fiscal year ending September 30th. Resettlements from Africa are less than half of the “ceiling.” In the Near East and South Asia, the administration set a fiscal year 2018 ceiling of 17,500 — as of the end of August, with one month of the fiscal year left, it had resettled 3,642.

Refugee arrivals from Europe, however, haven’t suffered. In fact, they smashed through their regional “ceiling” months ago, and haven’t slowed down since.

To people who already assume that the Trump administration is aiming to slow American demographic change by disfavoring nonwhite immigration, this may not seem surprising. But the reasons for Trump’s apparent refugee exception are more complicated than that.

In fact, the reasons that European refugees are still coming into the US in higher-than-expected numbers end up revealing why nearly everyone else is not. The Trump administration has deprioritized taking in refugees, from the explicit bans of Trump’s first year to a lack of investment in the infrastructure needed to vet people and bring them over in a timely fashion. The former Soviet Union is the exception that proves the rule.

The Trump administration is settling way fewer refugees than anticipated this year — but way more European refugees

How many refugees enter the US each year is basically up to the president and the executive branch to decide; they’re supposed to consult with Congress, but they don’t need to get formal approval. Before a new fiscal year, the State Department sends Congress its “Proposed Refugee Admissions” for the year, including numbers for particular regions (Africa; East Asia; Europe; Latin America and the Caribbean; and the Near East and South Asia) as well as a global estimate.

The Obama administration worked to increase the number of refugees — especially from Syria — in Obama’s last few years in office. In fiscal year 2016 (October 2015-September 2016), the administration basically met its target of resettling 85,000 refugees; for fiscal year 2017, which started in October 2016, it proposed bringing in 110,000 refugees.

Donald Trump and his administration do not share their predecessors’ sense of obligation to resettle refugees in the United States. To the contrary — during his first week in office, Trump signed an executive order (the first version of his “travel ban”) that attempted to stop all refugee admissions to the US for a few months, and to reset the refugee target for fiscal year 2017 to 45,000 instead of 110,000.

Federal courts stopped the administration from changing the targets for the year, but ultimately allowed Trump to impose a temporary ban on refugees who didn’t have “bona fide relationships” with a relative or business in the US. That meant that even though in theory the administration was still operating under the targets set by Obama, the total number of refugees resettled in fiscal year 2017 turned out to be a little over 53,000.

But for fiscal year 2018, the administration got to set its own target. It picked a radically low one — 45,000, with 50 percent reductions in the regional “ceilings” for each region — but one that it was assumed the administration would actually be able to hit.

With two weeks left in the fiscal year, it looks like the Trump administration will miss the expectations it set for itself this year as badly as it missed the targets set for all regions in 2017.

Except for Europe.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13071927/Refugee_targets_vs._resettlementsV2.jpg) Javier Zarracina/Vox

Javier Zarracina/VoxThe Trump administration proposed resettling 2,000 refugees from Europe in fiscal year 2018 (a 50 percent reduction from the fiscal year 2017 target). With a month to go, it’s already resettled over 3,000 from the region.

Trump is still resettling fewer European refugees than Obama did — the current stats are about 20 percent short of actual European refugee resettlements in fiscal year 2016, Obama’s last full year. But that’s not a big dip compared to refugees from the rest of the world from 2016 to 2018: a 39 percent reduction in refugees from Latin America and the Caribbean; a 72 percent reduction in refugees from Africa; a 74 percent reduction in refugees from East Asia; and a 90 percent reduction in refugees from the Near East and South Asia.

The bottom line is that refugee admissions have slowed down everywhere — but less in Europe than everywhere else.

The Lautenberg Amendment: Are Trump’s European “refugees” really refugees at all?

Every single European refugee taken by the US in 2018 has come from the former Soviet Union. That’s not a coincidence.

One of the pathways to come to the US as a refugee is to be a member of a group the US has identified as a specific “group of concern.”

People from the former Soviet Union who are members of religious minorities, and who have close family members in the US, are one of those groups,

This designation dates back, unsurprisingly, to the days when the Soviet Union wasn’t former at all. In 1989, thousands of Jews fled the crumbling USSR after decades of having been restricted from emigrating and persecuted at home — but the George H. W. Bush administration started denying some of their applications for resettlement in the US. The change alarmed then-Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ), who understood why they were fleeing — he’d traveled to the Soviet Union and met with Jews who were constantly watched by the Soviet regime, barred from attending universities, and even forcibly relocated due to their religion.

Lautenberg’s solution was enacted in 1990, and is still known as the Lautenberg Amendment. It explicitly lowered the standard for religious minorities in the Soviet Union to claim refugee status — instead of having to demonstrate that they had reason to believe they specifically would be persecuted, they simply had to demonstrate they were a member of a protected religious minority, and that that minority had a credible fear of being persecuted.

The Lautenberg Amendment isn’t saving Jews from Soviet authorities anymore. For one thing, the program now primarily serves evangelical Christians. For another, of course, the militantly atheist Soviet Union has been replaced as a regional hegemon by the Russia of Vladimir Putin — whose aggressive nationalism has become tightly entwined with the Russian Orthodox Church.

The Lautenberg program has experienced a huge surge of interest in recent years — after Russia’s 2014 partial invasion of Ukraine. Ukraine is by far the country that sends the most refugees to the US right now — over 4,000 in 2017, and over 2,000 in 2018.

That exodus is definitely a response to fears of Russia. But it’s less clear whether those are specifically fears about religious persecution or not. While Russia (and Russian-allied extremists in Ukraine and elsewhere) has persecuted Muslim Crimean Tatars and Jehovah’s Witnesses, attacks on evangelical Christians haven’t risen to that level. They haven’t gotten to the point of provoking people to flee their their homes.

The refugee agency HIAS (formerly the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), which has long taken the lead in resettling Lautenberg amendment beneficiaries in the US, argues that this means the Lautenberg program in the former Soviet Union doesn’t actually count toward the US’s contribution to the global refugee crisis. “It’s good for religious minorities,” says HIAS president Mark Hetfield, “but it’s not relevant to the 65 million displaced people globally” — and the latter is what matters in terms of global leadership on refugees. “These are not those people.”

And ironically, under Trump, that makes it easier to resettle them.

The bottleneck in the US refugee system

Proving you qualify as a victim of persecution is only part of the stringent vetting process for refugees. There are also layers of security checks performed by different agencies and capped off with an in-person interview conducted by a US official abroad.

This is where the refugee system is really struggling under the weight of the Trump administration. Administration officials told members of Congress this summer that over 100,000 people were being processed but hadn’t yet had in-person interviews yet — partly due to the fact that very few refugee officers were being sent abroad on “circuit rides” to interview applicants.

It’s easier to set up circuit rides in places where the US and UNHCR already have infrastructure — and in places where there isn’t an active conflict. That can mean that it’s hard to get to the populations (like Syrian refugees) in the most need. It usually means that the US takes a few years to really ramp up refugee admissions in a given location after deciding that people there are a priority.

The countries with the most refugee admissions to the US in 2018 — the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bhutan and Burma — are places prioritized in the last years of the Obama administration. But Bhutan and Burma were both winding down, as scheduled, in 2018; without an effort to identify new populations to invest in a refugee infrastructure for, the Trump administration will keep admitting fewer refugees in future years.

In the meantime, though, the reality of circuit rides makes it easier for people who live in countries that are relatively peaceful — like the former Soviet Union — and are seeking refugee status for reasons other than war.

But the interview is only part of the bottleneck. Another 45,000 would-be refugees had had interviews as of this summer, but were waiting for security checks to be completed — or had waited in the pipeline so long that their security approvals had expired and needed to be checked again. Under Trump, the FBI has been required to conduct checks on most or all refugees — without having added staff people to do it. (Officials told NBC News that FBI agents can sometimes only do a handful of checks in a day.)

Not all refugees are equal

The processing pipeline doesn’t move at the same speed for all applicants, however. Advocates are seriously concerned that it’s becoming a way to slow-walk certain refugees without having to officially deny their applications.

They’re particularly concerned about people from 11 countries where refugee admissions were suspended in late 2017 even after the 120-day global refugee ban had expired — including countries, like Syria and Iran, that had been sending the most refugees to the US in recent years.

Admissions from those countries have restarted, but only barely. 38 refugees from Iran, for example, have been resettled in 2018 so far.

The Department of Homeland Security stresses that people who come in under the Lautenberg Amendment are subject to the exact same security checks as any other refugee. But religious minorities in Iran are also supposed to benefit from the Lautenberg Amendment. And the added vetting requirements of the Trump administration have hardly affected both groups equally.

In April, a group of Iranian Christians who had fled to Austria sued the United States to reopen their asylum cases. They claimed they’d all been summarily denied at once — raising suspicions that they hadn’t flunked individual security checks, but were instead being denied out of an abundance of caution at best (and discrimination at worst). The judge has ordered the government to reconsider their claims.

The case has attracted some attention in the US because the Trump administration has sometimes claimed to be particularly sensitive to the persecution of Christians — indeed, religious minorities in the Middle East were exempted from the first version of the refugee ban.

In its day-to-day management of refugee admissions, though, the Trump administration isn’t putting a thumb on the scale to help Christians because it’s not putting that amount of effort in, period.

Few Trump administration officials would affirmatively defend the idea that the people who most deserve to be resettled in the United States, from anywhere in the world, are people who fear persecution from Putin’s Russia. But those are the only people for whom the administration is even close to meeting the low expectations it’s set — while, in the rest of the world, the doors are all but swinging shut.

Author: Dara Lind