The term has long been aimed at containing women’s power.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) wants people to know when “bitch” became a go-to insult.

“From 1915 to 1930, Madam Speaker, that word suddenly took off in usage … and you know why?” Jayapal said in a House floor speech this July. “Because in 1920, this body gave women the right to vote — and that was just a little too much power for too many men across the country.”

As Jayapal noted, the decades following women’s suffrage saw the rise of the term “bitch,” which is still frequently used against women today. It’s a point she emphasized while speaking in support of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez after a reporter witnessed Rep. Ted Yoho (R-FL) call her a “fucking bitch” earlier this summer.

According to a 2014 Vice report by Arielle Pardes, the use of “bitch” in literature and articles doubled between the years 1915 and 1930. While part of this surge was due to a spike in the word’s use to describe female dogs, as well as the rise in popularity of the term “son of a bitch,” some of this increase was also driven by its use as an insult against women.

“There is an uptick in use of ‘bitch’ as a term of abuse for women that starts gradually in the 1920s and 1930s, and then really gains traction in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s for a woman who is seen as conniving, malicious, or just plain bad,” says Kory Stamper, a lexicographer and former associate editor for Merriam-Webster dictionaries.

Although scholars are unsure whether this trend is directly tied to women’s suffrage, several noted that such backlash made sense and spoke to overwhelming discontent with women’s power.

“If there was ever a time for this term to gain prominence, it would be with the passage of the 19th Amendment, when women were given the right to have an independent voice,” says Kira Hall, a linguistics professor at the University of Colorado Boulder.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21766948/GettyImages_939665142.jpg) Ken Florey Suffrage Collection/Gado/Getty Images

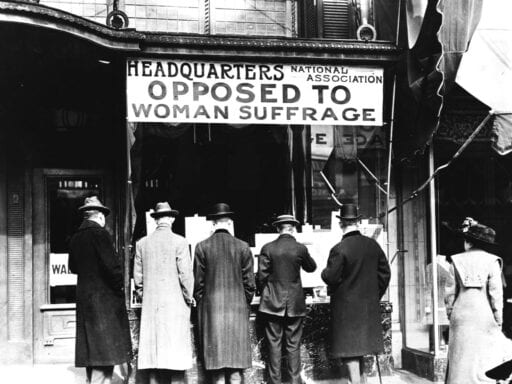

Ken Florey Suffrage Collection/Gado/Getty ImagesThe term “bitch,” after all, echoed the messaging of the anti-suffrage movement.

As anti-suffragists argued, if women were to leave the private sphere, or the home, for the public one, they would be stepping out of bounds. Using terms like “mannish” and “unsexed,” they sought to portray suffragists as encroaching on male gender roles. And in what historians see as a clear example of slut-shaming, they attacked women’s sexuality too, denouncing suffragists as “loose” women who had questionable social mores.

“Bitch,” a word that referred to an unpleasant or promiscuous woman at the time, was a slur designed to remind women of these same boundaries.

In retrospect, its emergence was distressingly unsurprising: Whenever women, minorities, or other groups have successfully gained greater power in America, they’ve seen swift backlash.

Although there are more women in Congress than ever — or perhaps because of it — those attempts to contain newly empowered groups continue, as Yoho’s comments toward Ocasio-Cortez made clear.

The rise of the term “bitch,” briefly explained

The word “bitch” has been around for some time, though it wasn’t directed at women until the 1400s.

As far back as 1000 AD, “bitch” was being used to reference a female dog, according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

By the 18th century, it had become “the most offensive appellation that can be given to an English woman, even more provoking than that of whore,” according to the Atlantic. And in the 1900s, its use soared, Zoë Triska writes for HuffPost:

The biggest rise of the word as an insult against women was in the 1920s. In 1915, most of the books and articles published used the word “bitch” only to refer to a female dog. However, in 1925, there were numerous articles and books that used the word as a slur against a woman or women. By 1930, the number of references that called a woman or women “bitches” outnumbered those that referred to dogs.

Much like the anti-suffrage movement, the term “bitch” was and is about containing women, says Karrin Vasby Anderson, a communications studies professor at Colorado State University.

Those who pushed back against the suffrage movement felt that women should remain exclusively in the private sphere, and argued that the country’s very democracy was at stake if they didn’t.

“The mother’s influence is needed in the home. She can do little good by gadding the streets and neglecting her children,” wrote California state Sen. J.B. Sanford, the chair of the state’s Democratic caucus, in 1911. “The kindly, gentle influence of the mother in the home and the dignified influence of the teacher in the school will far outweigh all the influence of all the mannish female politicians on earth.”

Opponents like Sanford believed that “as women crossed over into the public sphere of politics, they would be contaminated in terms of their values and morals, and they wouldn’t be able to raise the next wave of Democratic subjects,” Vasby Anderson told Vox.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21764027/484176257.jpg.jpg) Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

Transcendental Graphics/Getty ImagesAfter women obtained the right to vote — a change that initially applied exclusively to white women — the term “bitch” began to take off. Used to describe women who were too lewd or aggressive, it played on the same tropes as the anti-suffrage movement did.

As English professor Dolores Barracano Schmidt wrote in the 1971 paper “The Great American Bitch,” writers in the 1920s and ’30s established the idea of the “bitch,” or the difficult woman, as they grappled with shifting power dynamics in heterosexual relationships. “They are the hardest, the cruelest, the most predatory, and the most attractive, and their men have softened or gone to pieces nervously as they have hardened,” says an Ernest Hemingway character of these women.

Perhaps even more telling, writers sometimes used the term as an insult in the same way as “feminist,” Stamper notes. One such example was in Idabel Williams’s 1934 book, Hell Cat, when a female character was dismissed as both:

“He’s the mayor, isn’t he? He’s the most important man in town, isn’t he? And married to that —that bitch!” “Lula!” “I don’t care, I’ll call her that to her face, and worse. I’ll call her a — a feminist!”

Since then, “bitch” has been used in myriad ways. It was reclaimed by feminists in the 1970s. It’s become a verb. And it’s a moniker that makes frequent appearances in popular music and slang. Despite its evolution, however, the word is still often levied to undercut women in power.

“I believe that bitch is a metaphor that signals backlash, and backlash emerges when women are on the cusp of women achieving real power in politics,” said Vasby Anderson. “It’s a tool of containment because it’s a flag of somebody transgressing a boundary.”

During the 2016 election, phrases like “Trump that bitch” and “Life’s a bitch, don’t vote for one” were hurled against Hillary Clinton as sexist invectives. Yoho’s words, too, were aimed at dismissing Ocasio-Cortez’s authority as a Congress member after the two had a heated debate about police reform.

“What’s curious about the term ‘bitch’ is it takes on different power depending on who is using it,” says Jamie Thomas, a linguistics professor at Santa Monica College.

These terms were used to “contain” women — and they still are today

The language used by anti-suffragists and the prevalence of the term “bitch” since have both centered on treating women as if they should operate within a set of predetermined boundaries.

As is apparent by the pervasive nature of such terms, it’s clear that current efforts to take down women politicians are animated by the same fear of women taking power as was apparent in the 1920s and ’30s.

“Even 100 years after the 19th Amendment, it’s still hard for some people to take,” says Hall.

Recent iterations of such language include Trump’s fixation on the word “nasty,” an insult he’s aimed at Democratic vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris in an attempt to question her character and morality. “She was nasty to a level that was just a horrible thing,” Trump said last week regarding Harris’s questioning of now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

Then as now, however, women are not deterred. In the face of sexist slurs and treatment, they’ve continued to run for Congress in record numbers, pursue the presidency, and take on prominent leadership roles.

“There are going to be more of us here. There is going to be more power in the hands of women across this country. And we are going to continue to speak up,” Jayapal said in her floor speech.

Will you become our 20,000th supporter? When the economy took a downturn in the spring and we started asking readers for financial contributions, we weren’t sure how it would go. Today, we’re humbled to say that nearly 20,000 people have chipped in. The reason is both lovely and surprising: Readers told us that they contribute both because they value explanation and because they value that other people can access it, too. We have always believed that explanatory journalism is vital for a functioning democracy. That’s never been more important than today, during a public health crisis, racial justice protests, a recession, and a presidential election. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive, and advertising alone won’t let us keep creating it at the quality and volume this moment requires. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will help keep Vox free for all. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Li Zhou

Read More