The Vox staff reviewed all the finalists in each of five categories: fiction, nonfiction, poetry, translated literature, and young people’s literature.

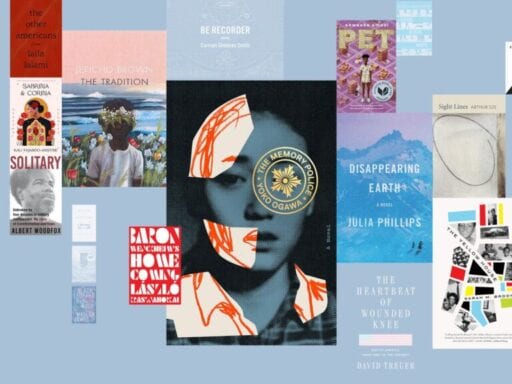

Every year, the National Book Foundation nominates 25 books — five fiction, five nonfiction, five poetry, five translated, five young adult — for the National Book Award, which celebrates the best of American literature. And every year (well, every year since 2014), we here at Vox read all 25 finalists to help smart, busy people like you figure out which ones you’re interested in. Here are our thoughts on the nominees for 2019. The winner will be announced Wednesday, November 20.

Fiction

Trust Exercise by Susan Choi

Trust Exercise is a viciously elegant novel with a structure so sharp it cuts. It concerns a group of young teenagers at a performing arts high school, a bunch of high-achieving theater kids always trembling on the edge of hormonal overload. Two of them, David and Sarah, are enmeshed in a torrid will-they-won’t-they affair; their charismatic acting teacher, Mr. Kingsley, forces them to mine that relationship for stage material repeatedly in front of their classmates.

That’s the first section of Trust Exercise, and as compelling as it is — Choi renders the insular world of a theater kid’s high school with claustrophobic intensity — it’s mostly setup. The real story comes in the second two acts, in a twist I won’t reveal here. But what ensues is an extended meditation on trust: trust between lovers, between student and teacher, between actor and director — and the trust that is implicit and unspoken in novels themselves, that lies between the author who writes the novel, the characters who enact the novel, and the readers who read the novel.

Choi plays with our trust, dancing right up on the edge of betraying it, again and again throughout Trust Exercise. But she does it so skillfully, with such intelligence, that all you can feel as you read is delight at having been fooled so well.

—Constance Grady

Sabrina & Corina: Stories by Kali Fajardo-Anstine

Sabrina & Corina is a world inhabited as much by personal and political history, and the dead, as it is by Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s stunningly realistic protagonists.

The 11 stories in her literary debut are, first and foremost, a beautiful testament to Denver, Colorado’s indigenous Latina women. Whether it’s Corina reckoning with the murder of her strangled cousin Sabrina, who in the titular story becomes “another face in a line of tragedies that stretched back generations,” or children loving addict parents too “caught in [their] own undercurrent” to be present, the notion of legacies is of utmost importance. And those legacies concern familial blood, yes, but the long history of racism, poverty, and violence, too.

It’s not so much that Fajardo-Anstine’s female leads are haunted by this. It’s more that navigating the events of the past is a central part of their stories. These are women persisting, and doing so with poise and power. They are figuring out what it means to be a woman — to have ties to Denver that run so much deeper than the white transplants who “came with the tech jobs and legalization of weed;” to reckon with mortality; and to try to love family, partners, and one’s self, even when that love is imperfect.

It’s a terrific debut, varied enough to be consumed all at once, but worth savoring.

—Caroline Houck

Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James

Black Leopard, Red Wolf is stunningly ambitious and epic. It’s also deliberately, and at times frustratingly, opaque.

The first in a planned trilogy, Black Leopard, Red Wolf takes place in a fantasy land rooted in pan-continental African folklore. There, a boy has gone missing, and a scrappy team of adventurers has assembled to find him.

The plan is that each volume of this trilogy will retell the story of the quest for the boy from a different point of view, Rashomon-style. In this first volume, we see it from the perspective of Tracker, who is basically a magical medieval African Philip Marlowe. Pointedly, Tracker has no emotional attachment at all to the missing boy; also pointedly, he tells us in the very first line that the boy is now dead.

This book is deliberately structured to thwart the reader’s desire for a traditional narrative arc. It’s also structured to thwart their desire for clarity. James withholds proper nouns from his sentences until the last possible moment, which means that as you read, you generally can’t tell who’s doing what at any given moment: you just get an impression of anonymous limbs tangled together in sex or battle. And that opacity seems to be key to James’s ambitions for this trilogy — but it also means that Black Wolf, Red Leopard can be a bit of a slog, because it is not interested in giving its readers anything solid to hold onto.

Still, James’s imagined landscape is lush with bloody and magical details, and the queer romances at the heart of the novel are immensely tender. If nothing else, this book is worth checking out for the sheer scale of the thing.

—Constance Grady

The Other Americans by Laila Lalami

Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans opens up with the protagonist, Nora, receiving the news that her father was killed in a hit and run. As she and her family grapple with this sudden loss, Nora finds herself on a mission to discover what actually happened to her father. But what she learns about her father’s life ends up disappointing her.

Even though Nora is the main character, each player has a chance to tell how her father’s death changed their life. And as their perspectives push up against Nora’s, Lalami begins to delve into the struggles of immigrant families. The chapters from Nora’s perspective juxtaposed with the ones from her mother’s show how both struggle with what it means to be Moroccan and American. Other chapters show readers how even an event as intimate as death can be inflected by your race, your ethnicity, and how safe you feel in the US.

And as Nora searches for answers, Lalami slowly reveals how the environment for Muslims, immigrants, and people of color in a post 9/11 US contributed to the chaos around the death of Nora’s father.

—Rajaa Elidrissi

Disappearing Earth by Julia Phillips

Julia Phillips’s riveting Disappearing Earth is technically a novel, but it reads more like a collection of short stories. The book is set in Kamchatka, a remote peninsula in Russia’s Far East that is inaccessible by land from the rest of the country, and starts with the disappearance of two young sisters, which nearly everyone across the small peninsula hears about. Each subsequent chapter, however, tells a new story from a new character’s perspective rather than following the missing girls’ story in a linear way.

Through these women’s stories, we get a glimpse of how the girls’ disappearance has rippled through the broader Kamchatka community, but we also hear more about how each of them struggle with the limitations they come up against in their everyday lives in Kamchatka. Some of the women are bored and trapped in unhappy relationships; others are frustrated by the lack of economic resources keeping them stuck in Kamchatka when they long to leave the peninsula and live in Europe; others grapple with the dynamics between white Russians and the indigenous Even people. The peninsula of Kamchatka is almost a character in and of itself, shaping how each of these women view the world and their opportunities within it. The stories seem disconnected at first, but the characters’ paths start to overlap toward the end of the book for a surprising ending that you won’t want to miss. It’s a breathtaking page-turner of a novel that covers some very 2019 themes, all while set against the beautiful backdrop of Kamchatka.

—Nisha Chittal

Nonfiction

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broome

I still haven’t been to New Orleans. And everything I know about New Orleans comes from friends’ stories (“it’s very humid, you’d hate it”), travel shows spotlighting the food (shrimp etouffee, beignets, gumbo with a roux dark as cocoa powder), and articles about how Katrina and its annihilative waters drowned the city; stories of how, to this day, the trauma of Katrina fundamentally changed the soul of New Orleans.

What this knowledge amounts to is superficial stuff that would pass at a cocktail hour. Sarah Broom’s revelatory memoir, The Yellow House, is not that.

Broom’s story is about Katrina, but it isn’t just about the life-shattering chaos of the storm. The Yellow House is about her family, the non-French Quarter pockets of New Orleans that America forgot about or chose to forget, and the myths of prosperity perched atop the rot of corruption. Ultimately, The Yellow House is about the price the city’s black men and women have paid for it.

Broom grafts these narratives onto the bones of her family’s yellow house, purchased by Broom’s mother Ivory Mae in 1961. Its appearance on the outside was a facade for its structural disorder the inside. The house witnessed what Broom’s family — Broom has seven siblings — did not show to their friends, the interior anarchy that never slipped beyond the home’s raw walls and broken doors.

Katrina’s cataclysmic fury destroyed the house, like it did New Orleans. But that’s just the beginning of Broom’s powerful story.

—Alex Abad-Santos

Thick: And Other Essays by Tressie McMillan Cottom

Thick: And Other Essays isn’t a conventional personal essay collection. But Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom, who holds a PhD in and teaches sociology, makes it a point to bill it as an eight-piece “portrait of her own life.” She affirms that by focusing on contemporary black womanhood, digging into challenging concepts like the societal difference between “black blacks” and “black ethnics.” And with the title essay — about the size of her body in relation to white beauty standards — serving as table setting, Cottom’s intent becomes clear: She is defining the truth of her own existence, and deconstructing white Americans’ reactions to her doing so.

For the well-read black woman, Thick won’t be a consistently revelatory read. As Cottom herself notes in one of the later essays, there is a growing, if small, cohort of writers online and in print who do a great job covering the intersecting political and personal elements of black feminism. But Thick is nonetheless a significant — and very readable — academic exploration of topics like black girlhood, black intellectualism, and black aesthetics.

—Allegra Frank

What You Have Heard Is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance by Carolyn Forché

Poets write the best memoirs, and Carolyn Forché’s What You Have Heard is True is no exception. It’s Forché’s chronicle of a life-altering encounter with Leonel Gómez Vides, an activist who opened her eyes to what was going on in his native El Salvador: poverty, unrest, injustice, and much unease.

It was the late 1970s, and Forché, who had just published her first book of poetry, was teaching. But at Gómez’s invitation, she traveled from her home in California to El Salvador and then embarked on a tour around the country with Gómez. The book is a lyrical and pristinely disturbing recounting of that time, and how it awoke within her a calling.

The subtitle of What You Have Heard Is True is “A Memoir of Witness and Resistance” — two things, it seems, that Forché learned from Gómez are closely intertwined. He is constantly asking her to not just see what is going on around her as she travels with him, but witness it, to understand it and then gather the courage to speak and write of it.

The decades since are evidence that Forché took that charge seriously; since that time, she’s called herself a “poet of witness.” But though it’s prose, What You Have Heard is True is no less stunning than her poetry — sharp, unsparing, and never looking away.

—Alissa Wilkinson

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present by David Treuer

Five hundred years after Columbus “sailed the ocean blue,” it’s impossible to buy into the white colonialist lore of America, land of the free. We are well aware of the slavery, slaughter, and rape of American Indians and the stripping away of their land and resources, which are the tenets of their spirituality. In The Heartbeat at Wounded Knee, however, David Treuer pushes the reader beyond this narrative of sadness, defeat, and cultures ruined. After the brutal massacre of 150 Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee Creek in 1890, there was not simply “an Indian past” and “only an American future.” The story of American Indians is a testament of insistent, persistent survival.

Treuer weaves in written history, reportage, and personal stories to complete this record of who Indians are post-1890 and who they always have been; he is not content to let Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown, a white man, be the last, defining word on the Indian. While some of the historical passages on legislative bills and treaties come across a little stiff compared to the intimate portraits — like a cousin learning to channel his rage through MMA fighting or the young Indian who is finding community online — these legal and congressional battles remain vital to understanding how Indians have endured.

To be clear, Treuer is not interested in happy, shiny anecdotes of Indians returning to old ways on the reservation or making successes away from it; he portrays the nuance: what it is like to carry your peoples’ history of fighting literal wars, anger, the bottle. The everyday living of raising kids, making mistakes, working rodeos, foraging for pinecones, selling weed. Being downright, utterly scrappy. The reality of the American Indian is very much the reality of America.

—Jessica Machado

Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement, My Story of Transformation and Hope by Albert Woodfox with Leslie George

Robert King, Herman Wallace, and Albert Woodfox were the Angola Three — three inmates of the notoriously harsh Louisiana State Penitentiary who each spent decades in solitary confinement. Woodfox, the last of the three to be freed, spent 42 years in solitary before his conviction was overturned in 2016. Solitary, his memoir of surviving the longest sustained period of solitary confinement in US history, is a vital first-hand account of carceral brutality, told with astonishing aplomb.

Woodfox and his cowriter Leslie George always use the same measured, even tone, whether they’re describing Woodfox’s childhood in the Treme, New Orleans brutal Sixth Ward, or long-ago crimes — knocking a girl out with a chair or borrowing buggy horses to ride them, desperate for any release he can get. That understatement becomes a strategy when Woodfox is sentenced to Angola — a prison erected on a former slave plantation — for robbery and abruptly enters a nightmare; it’s a scene that, like many others, makes use of the N-word to underline its generally unsparing view of violent racism.

Woodfox rattles off detail after detail of the hellscape he’s thrust into — a bogglingly complex ecosystem of violence and corruption. “It’s painful to remember how violent Angola was in those days,” he says at one point. “I don’t like to go into it.” But he does, with prose that shocks because it is so readable, plainspoken, and awful; by the time he’s recounting his experience of a claustrophobic panic attack while doing his first stretch in the 6-by-9 solitary confinement cell, a reader might feel claustrophobic, too.

It seems unthinkable that anything can be uplifting in such a place, but the collective spirit and sense of brotherhood among the Angola Three sustains and animates their long, grueling fight for freedom, even through the agony of Woodfox having his conviction finally overturned only for the state to retry and re-convict him. The laborious nature of court proceedings in this context is mainly a reminder that the system can dehumanize its victims in even the most trivial ways; Woodfox is never more passionate than when he’s tearing apart the unsourced and fabricated claims made about him in legal affidavits.

Such callous details, juxtaposed against the larger-than-life horrors of Angola, make Solitary a must-read look at the justice system, and of humanity struggling to endure in the most abject and frustrating conditions. “Don’t turn away from what happens in American prisons,” he writes, simply, in the end. After reading Solitary, you never will again.

—Aja Romano

Poetry

The Tradition by Jericho Brown

It’s always tricky for me, picking up a new book of poetry. I wonder, will it speak to me? Will it reward whatever work I have to put in to understand it? Fortunately, Jericho Brown’s The Tradition pays off on the first page (which opens with “Ganymede,” in which he reimagines the Greek myth: “I mean, don’t you want God/ to want you?”) and just keeps on giving.

The writing is clear and precise throughout; the topics are modern and rooted in the writer’s culture, but they’re still universal enough to speak to a reader outside that culture. It can be considered slander to call poems “accessible” — as though the only way poems can mean is through the hard work of unlocking all the doors and opening all the windows of a poem’s secret house. Brown’s poems are accessible the way your friends are accessible: They invite you in, sit you down, talk to you about things that matter in words that revel in their beauty. Please, let’s celebrate the radical accessibility of these poems.

Also, I am a sucker for form. Sonnets? Villanelles? Yes, please. When I read the first Duplex in the book (a form invented by Brown), I thought, “Ooh, nice trick, well executed.” But there were four more in the collection, each cleverer than the last, and as I read, I became a Jericho Brown fan for life. Writing is good words in good order; poetry is the best words in the best order. Brown’s words are in the best order possible.

—Elizabeth Crane

“I”: New and Selected Poems by Toi Derricotte

In this 298-page book, containing selections from 40 years of work plus more than 30 new poems, Toi Derricotte invites the reader into an intimate portrayal of trauma, struggle, and triumph. Many of the poems take the shape of stories, feeling like autobiography, a mix of musing and memories.

Derricote’s writing can be beautiful, horrific, and sometimes laugh-out-loud funny, as she explores identity, race, gender, and everyday delights. In one section, harrowing first-person accounts of child abuse live next to touching odes to a pet fish (“Joy is an act of resistance,” she writes). Another provides an unflinching perspective of giving birth without drugs.

Some of Derricotte’s most moving work addresses personal and collective trauma, like this section from the new poem “Pantoum for the Broken”:

Some forget but their bodies do inexplicable things.

We don’t know when or why or who broke in.

Sleepwalking, we go back to where it happens.

Not wanting to go back, we make it happen.If we escaped, will we escape again?

I leapt from my body like a burning thing.

Not wanting to go back, I make it happen

until I hold the broken one, hold her and sing.

In another new poem, she writes, “I see what a great gift it is if a writer just truthfully records the way her mind moves.” Derricotte gives us that gift, too.

—Susannah Locke

Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky

For protest art, you can look to the novelists and essayists, but the ones who leave you feeling socked in the gut are the poets, and Ilya Kaminsky is aiming his blows straight at our churning stomach. His first full-length collection, Dancing in Odessa, was released in 2004, which means expectations were at a fever pitch for Deaf Republic. And by my lights, it doesn’t disappoint.

Deaf Republic is the story of a town, told in a series of poems, in which a young deaf boy named Petya is killed by soldiers as they seek to break up a protest. In response, the townspeople begin to feign deafness in the face of the soldiers, fomenting a revolution of a kind. But Kaminsky, who lives with hearing impairment and whose family fled his native Odessa when he was 16, seeking political asylum in the US, knows deafness firsthand and how to make it into a metaphor. It’s a double-edged sword, this deafness: On the one hand, it’s a silent but powerful protest; on the other, it suggests that we can shut ourselves off from one another’s suffering.

The opening poem, “We Lived Happily During the War,” positions the story that follows as partly, but explicitly, the American story:

And when they bombed other people’s houses, we

protested

but not enough, we opposed them but notenough. I was

in my bed, around my bed Americawas falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house.

And the final poem, ironically titled “In a Time of Peace,” begins by reminding Americans that this story, of Petya and the deaf town, is ours:

Ours is a country in which a boy shot by police lies on the pavement

for hours.

We see in his open mouth

the nakedness

of the whole nation.

We watch. Watch

others watch.

Deaf Republic is harrowing and damning, if we dare to listen.

—Alissa Wilkinson

Be Recorder by Carmen Giménez Smith

At first, it might seem like Be Recorder is looking for an argument. Some early poems almost take the form of tiny essays. They lay bare the oppression and dismissal of marginalized people, even in supposed safe spaces.

After being mistaken for another woman with “what you might call a brown name,” the narrator in “Origins” boldly asserts her selfhood through her poetry: “here I am with a name that’s at the front of this object, a name I’ve made singular, that I spent my whole life making.”

But Be Recorder is more than one origin story, and Carmen Giménez Smith shows resistance and resilience are not always rewarded. (One line of startling clarity in “Self as Deep as Coma”: “To end a conversation, tell a story of suicide with a girl in it.”)

Identity and argumentation soon break down. The titular poem is long and fragmented: “Poetry v prose” is the first in a long list of dichotomies that collapse onto each other, and the arbitrary hierarchy of the animal kingdom stands in for the arbitrary hierarchy of nations. Giménez Smith asks if the immigrant is doomed to be seen as an albatross, a mere symbol: “am I the mariner / and whose bird was it”

will I be reincarnated as elephant

as king as flea as barnacle

why am I the locus of your discontent

and not your president

your intimate the landlord

an aesthetic landlord

how do I hang from your neck

with such ease and when

will I be graced with immunity

—Tim Williams

Sight Lines by Arthur Sze

Sze’s tenth volume of poetry is a kaleidoscope of juxtaposition, layered stacks of images from across time and space, presenting a deeply interconnected feel of the universe. Let me give you a taste:

“in the desert, a crater of radioactive glass—

assembling shards, he starts to repair a gray bowl with gold lacquer—

they ate psilocybin mushrooms, gazed at the pond, undressed—

hunting a turkey in the brush, he stops—”

Awash in nature and unafraid of science, Sze’s poems use languages’ sounds in a lovely way, while addressing the world’s horrors.

In some poems, he writes from the perspective of a voiceless, lowly natural thing — lichens, or in this example salt:

“… in Egypt I scrubbed the bodies of kings and

queens in Pakistan I zigzag upward through twenty-six miles

of tunnels before drawing my first breath in sunlight if you

heat a kiln to 2380 degrees and scatter me inside I vaporize

and bond with clay in this unseen moment a potter prays

because my pattern is out of his hands …”

—Susannah Locke

Translated Literature

Death Is Hard Work by Khaled Khalifa, translated by Leri Price

In Khaled Khalifa’s version of Syria, death is the easy part. Living and finding meaning in a country wracked by civil war and mass atrocities proves much more difficult.

Three siblings, Bolbol, Hussein, and Fatima, navigate their broken worlds as they attempt to take the body of their father Abdel Latif for burial back in the hometown he fled many years before. Death Is Hard Work captures their frustration and dissociation with violence as they physically and metaphorically traverse the divides of their country. They are forced to face their own issues with each other, problems that lead them back to the frustrations with the dead man wrapped up in the back seat. War in this novel is messy in a way that goes beyond airstrikes and refugee flows.

At 180 pages divided into three parts, Khalifa oscillates between complexity and simplicity. We’ve all felt like Hussein, struggling to feel important, or like Bolbol, swinging back and forth between thinking of himself as a brave hero and thinking of himself as a cowardly outcast. But the numbness, the blasé nature of tragedy, grant this novel both its undercurrent of dark humor and the fog that lies over its happiness and places the reader deep in the throes of the conflict in Syria. Revolutionaries or rebels, like Abdel Latif, find vigor and life in the hope of breaking the chains of the regime, but those left behind by their seemingly inevitable deaths feel the weight of fear and suffering.

The beautiful translation comes courtesy of Leri Price and holds on to the integrity of Khalifa’s purpose and compelling prose. Normally banal encounters of checkpoints and falling asleep depict the real cost of war. One recurring metaphor imagines the opportunity for love as a bouquet of flowers floating down a river. And the ignored, rotting corpse of the siblings’ father becomes a potent symbol of all that the siblings can’t bear to face, all of the greater tragedies they ignore so that they can focus on the surface-level injustices against them. After they bury their father, the siblings leave each other with little more than a wave goodbye, relishing their return to the hard work of waiting to die.

—Hannah Brown

Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming by László Krasznahorkai, translated by Ottilie Mulzet

With Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, László Krasznahorkai closes out his gargantuan four-part literary quartet, begun with his first novel Sátántangó in 1985, and continued in The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), War and War (1999), and finally Baron Wenckheim. (The first two books were turned into cinematic masterpieces by Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr.) You thankfully don’t have to have read the earlier novels to get through this one, but when characters have cosmic visions of Satan dancing into eternity, it helps to understand that Krasznahorkai has woven certain motifs throughout his tapestry of vanishing Hungarian pastoral life. In Krasznahorkai’s writing, the banal and the quotidian are constant gateways to mystical revelations and Kafkaesque insights about our absurd postmodern world — or at least, they could be, if his characters, and we as ride-alongs, could only manage to catch them before they vanish into ephemera.

Baron Wenckheim concerns a retiring man who returns home to his tiny Hungarian village, only to be met with scheming and manipulation from many of its desperate and desolate inhabitants. Anyone focusing too much on the plot, though, will miss the trees for the woods, because the real draw of this shamelessly performative experimental fiction is the endless metaphysical abyss of Krasznahorkai’s prose: uninterrupted stream-of-consciousness passages that last for chapters with no breaks of any kind, ruminate simultaneously on the cosmic and the mundane, and fold endlessly onto themselves in a hopeless existential ouroboros, perpetually advancing and retreating before the impossibility of grasping the self and the universe. For example:

… because in reality the fear that existence will cease, and that always in a given case it will cease, is the most elemental force that we know — and if we can’t really enclose this fact in a nice, little box, if we were nonetheless to place all our most significant knowledge in a capsule and shoot it off to Mars — if we could finally make up our minds and leave behind this earth, which in general we don’t deserve (although who knows who’s in charge here?), well — and so here we are again, back with fear … because just think about what that means: fear, if we regard it as a creationary force, a general power center, from which the gods evaporate, and finally God emerges …

This approach predictably doesn’t add up to tidy narrative conclusions. But if such whirling philosophical exercises rejuvenate and invigorate you, then Krasznahorkai’s works are calling your name.

—Aja Romano

The Barefoot Woman by Scholastique Mukasonga, translated by Jordan Stump

The Barefoot Woman is an elegiac tribute by Scholastique Mukasonga both to her mother, Stefania — the focal point of the book — and to what life was like for Tutsi residents in Rwanda before the devastating 1994 genocide, when many members of her own family were killed.

Even as it captures the ever-present anxiety in a community racked by violence, The Barefoot Woman also centers heavily on the routine, day-to-day acts that families engage in as they try to build a home together. The book, which is translated from French to English, is as much about commemorating and remembering the sorghum harvest rituals Mukasonga participated in and her mother’s matchmaking prowess as it is about capturing the fear and anguish that her family experiences.

Ultimately, The Barefoot Woman is meant to serve as its own marker, not only of the atrocities that have been committed but also of the people these acts attempted to erase. Mukasonga writes to her mother, “I’m all alone with my feeble words, and on the pages of my notebook, over and over, my sentences weave a shroud for your missing body.”

The book is a testament to her memory and her life.

—Li Zhou

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa, translated by Stephen Snyder

Yoko Ogawa focuses on the materiality of life on a small, unnamed island in The Memory Police. That’s because the premise of her dystopian novel is that the objects that enrich life — books, perfume, roses, birds — are systematically disappeared along with the characters’ memories of them, enforced by a fascist regime.

The horror of forgetting is baked deeply into this novel. The narrator is an unnamed novelist whose mother was murdered by this regime because she had the power that few on the island have: to remember. The novelist’s editor, named simply “R,” also has this power, so the narrator hides him in a bunker in her home. The novel they are writing appears in occasional passages as a mise en scene; it’s about a woman who loses her voice, an image that mirrors the novelist’s own fears of how she’ll continue to write while losing words.

The narrator’s only other relationship is with an elderly man she colludes with to hide “R”; he was once the island’s ferry captain before ferries vanished. Whenever another beloved object disappears, the old man responds with empty maxims — “time is a great healer” — or reassurances — “maybe some other flower will grow in its place,” after roses disappear. His character represents the most haunting aspect of Ogawa’s book: the adaptation and quiet resignation that enables an oppressive regime.

—Laura Bult

Young People’s Literature

Pet by Akwaeke Emezi

Jam thinks she lives in a utopia in Akwaeke Emezi’s bittersweet and unsettling YA novel Pet. The largely unspecified revolution happened before she was born, and she now lives in a world free of police violence, of domestic abuse, of injustices big and small. A trans girl, Jam received care that let her socially transition at 3 and physically transition in her teens. The point is: The monsters are gone and the world is better.

Or is it? A strange, lumbering beast crawls out of one of Jam’s mother’s paintings and makes itself known to Jam, who dubs it Pet. Pet says it is hunting a monster, right there in Jam’s supposed utopia, and the thrust of Pet involves Jam learning that monsters are not confined to history books.

This is a fable, more or less, but it’s a lovely and loving one, with genuine affection for every character who is even briefly introduced. The relationship between Pet and Jam has real heft, even if this is yet another tale of a normal girl and a magical creature. But the really thoughtful idea here is Emezi’s dissection of what justice means, even in a supposed utopia. It’s fleeting, and you have to fight for it — over and over and over again.

—Emily VanDerWerff

Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks by Jason Reynolds

This is YA author Jason Reynolds’ second National Book Award nomination. Like his previously nominated work, 2016’s Ghost, Look Both Ways channels his vivid voice and his deadpan but tender portraiture of kids growing up in the city, with all its excitement and complexity and cacophony.

In Look Both Ways, Reynolds turns that noise into a polyphonic character study of the city. Billed as a story told in 10 blocks, Look Both Ways channels Armistead Maupin’s Tales From the City, unfolding through the varied viewpoints of a class full of children as they walk home from school every day, navigating their respective city streets. Their lives bypass and occasionally intersect with each other, and as the book unfolds, the reader discovers the physical and human geography of the city.

These kids’ adventures are granular. They are formed moment by moment, block by block: from the ragtag gang who pools their resources to turn 90 cents into an unforgettable memory, to the boy fighting a panic attack when his daily route home is upended, to the kid who expresses a wealth of inarticulable emotions by grabbing a fistful of roses. It’s less a novel than a protracted tone poem, with striking imagery (“He watched his classmates tap-dance with tongues” … “For him, the hallway was a minefield, and there were hundreds of active mines dressed in T-shirts and jeans”) accented with subtle commentary on a host of social issues, from health care and poverty to homophobia and bullying. The prevailing takeaway, though, is a sense of indomitable wonder, girded by Reynolds’ underlying confidence in his city kids. They’re doing just fine.

—Aja Romano

Patron Saints of Nothing by Randy Ribay

Randy Ribay has packed a lot into this YA novel. It’s got the requisite messed-up family dynamics, the teen unsure of his path forward, and the love interest, but the real focus is a murder mystery pursued by a total amateur in a faraway country, a place where he doesn’t speak the language and doesn’t always know who to trust. Throw in more than a splash of misdirection and some pretty pointed opinions on the political situation in the Philippines, and you’ve got an out-of-the-ordinary story.

Jay, a Filipino American high school senior with no enthusiasm for college, travels to the country his parents left when he was a baby to solve the mystery behind his cousin Jun’s death. Jun is set up as a saint, an impossibly empathetic paragon who is wildly misunderstood by his authoritarian parent (who is an actual cop, as if we needed the emphasis). Jay rides to the rescue of his younger girl cousins and his whole sad family, but he gets so many things wrong and has to learn real truths instead of relying on his idealized version of events. It’s just like in life.

Some of the “kumbaya” family healing at the end feels forced, but Ribay deals well with the emotions and compromises tragedy forces on people. And the plot never gets lost in its march toward understanding, despite the silent family members, the college plans gone awry, and the crush who may or may not be actually interested. I found myself caring more for the flawed, dead Jun than for the Jay who still has his life ahead of him, but I couldn’t help rooting for Jay to figure himself out.

—Elizabeth Crane

Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All by Laura Ruby

Thirteen Doorways is a ghost story, told by the ghost.

Teenage Frankie, getting by in a World War II-era orphanage with her bratty sister Toni, is mostly unaware that she’s being haunted by the long-dead narrator Pearl. But she’s plenty conscious of the other spectral presences in her life: the missing humanity of cruel head nun Sister George; the absence of her very-much-alive father, who abandoned his children; the lack of joy or light or meatball sandwiches at the orphanage. And now, the list includes her brother Vito — her father reappears only to take Vito to Colorado with their new stepmother and step-siblings, leaving Toni and Frankie behind.

Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All is a story of female anger and pain — about how terrible it was to be a girl in the past, and the past before that, and the past before that. It’s a story about the fear and shame and determination that an unfair life instills in the women those girls become, or never get to become.

There are some familiar beats (orphans bond; teens have crushes; ghosts can’t quite comprehend their own deaths; women with spirit find that spirit violently quashed), but the language is moody and engaging (at one point, phantom Pearl describes herself as “ghostful”), and the truth of the central theme — that danger lurks around every corner — resonates. It’s a story about very real helplessness that manages a glimmer of hope.

—Meredith Haggerty

1919: The Year That Changed America by Martin W. Sandler

Yes, this book exists mostly because 1919 was exactly a century ago. But 1919: The Year That Changed America makes a compelling case for both itself and its title.

This is a children’s history book that has the wit to open with a giant flood of molasses. But it doesn’t shy away from the more solemn tales of a revolutionary moment in US history: 1919 thoughtfully covers the women’s suffrage movement (and the racism it did not expel), the violent suppression of labor and African American civil rights movements, and the Red Scare that helped fuel these crackdowns.

I’m very sorry to note, then, that this very website has debunked the myths around Prohibition — the other big event of 1919 — and Martin W. Sandler’s history seems to miss the mark here. Despite careful inclusion of revisionist sources elsewhere in the book, the author does not cite any in this section.

The conventional story the book imparts is captured by the pull quotes (eye-catching with smart use of color, thoughtfully designed like the rest of the book). One from historical aphorism repository H.L. Mencken is so sweeping, it approaches parody: “There is not less drunkenness in the republic, but more. There is not less crime, but more. There is not less insanity, but more.” But substantial evidence suggests Prohibition really did reduce problem drinking and didn’t increase crime overall, even if organized crime benefited from the legislation.

1919 does invite readers to weigh the costs and rewards of other public health interventions — including gun control. But, say, a debate over a higher alcohol tax? Maybe that will make it in in 3019.

—Tim Williams

Author: Constance Grady

Read More