If all the church’s ministers were out of town, we’d have a visiting preacher. One frequent visitor was a kindly British man who had been the church’s pastor years ago and retained an “emeritus” title. Whenever he filled in for a service, he requested that we sing the same hymn — “There is a Balm in Gilead,” the traditional African American spiritual. There are many versions of the song, which has morphed through centuries of American history, but the version in our hymnal had this refrain:

There is a balm in Gilead,

To make the wounded whole;

There is a balm in Gilead,

To heal the sin-sick soul.

“Gilead” is a Biblical place, but it’s called up in American culture over and over. The old hymn evoked it for more than a century before it was picked up as a song of protest and liberation by the civil rights movement. More recently, it’s been the name of a sleepy fictional mid-century Iowa town for a trio of award-winning novels by Marilynne Robinson. And it’s the much darker setting for a dystopian fundamentalist republic in Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale and Hulu’s TV adaptation.

These seem unconnected, but for one thing: the name. And that’s significant, for a revealing reason.

Some Biblical scholars think the word “Gilead” means “hill of testimony.” So it may not be all that surprising that the concept of testimony — of crying out, of speaking up, of not being silent — is what links all three of these invocations of Gilead. Old American attitudes about who belongs in our cities and towns and who does not also thrum beneath these stories.

Even more fundamentally, the reasons those attitudes remain are there, too: the shame and fear that govern systems that push people away from one another in both free lands and fascist ones. Not everyone has always gotten to speak in their own voice.

Gilead, explained

Gilead, an area east of the Jordan River, shows up a few times in the Bible. Most significantly, it’s the place in the book of Genesis to which the patriarch Jacob flees from his father-in-law Laban with his two wives, their two handmaids, and his brood of children, including the 12 sons whose descendants would become the tribes of Israel.

The hymn’s lyrics, though, are a quotation from another part of the Bible. The song is old, its precise origins hard to trace, but it refers to Jeremiah 8:22, in which the prophet is delivering a message from God mourning the hard-heartedness of the people and weeping for their exile from their homes. At the end of the chapter, Jeremiah’s message from God says, “Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there? Why then is there no recovery for the health of the daughter of my people?”

Some readers of the Bible link that lament with the arrival centuries later of Jesus, who was to be a “balm” to soothe the soul. During the civil rights movement, the song took on special significance as a song of both lament and hope: “Some times I feel discouraged, / And think my work’s in vain, / But then the Holy Spirit / Revives my soul again.”

Like most spirituals, it’s been recorded over and over by the greatest singers alive, probably most famously by Mahalia Jackson in a live Easter Sunday concert in 1967:

Jackson knew a thing or two about being a ”wounded” soul — she recorded the song near the end of her career, after years of involvement with the civil rights movement. Her rendition is slow and meandering, with lilts that lift the melody and then drop it again into quietness. It mixes notes of joy with the feeling of having seen and lived through a lot, having seen your friends submit to unbelievable treatment from their neighbors, and having learned the ability to just keep going on, without fear.

And so there is probably a reason that “There is a Balm in Gilead,” a spiritual first sung by black Americans shaking free from slavery, became important for the civil rights movement. Coretta Scott King wrote in her autobiography that her husband would quote the song when “he needed a lift.” Singing together, they were encouraging each other, telling what they saw, testifying to what they lived through, and reminding one another why they kept going.

Robinson’s Gilead is a “shining star of radicalism” that’s been eroded by fear

I hadn’t sung “There is a Balm in Gilead” for years when I ran across Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead, but I assumed it was named for the hymn. I found myself humming it often when I finally picked it up to read it, one hot late summer day.

The book’s fictional narrator, a Congregational minister named John Ames, lives in Gilead, Iowa. So did his father, and his grandfather, all Congregational ministers, all named John Ames. It’s 1956 in the book, the same year that Mahalia Jackson met Martin Luther King Jr. and sang at a rally to benefit the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. Our narrator is in his 70s, and he’s writing letters to his young son.

His family has a history of concern not just for the church, but for justice. John Ames’s father was a pacifist. His grandfather was a fearless, fiery abolitionist who served as a chaplain with the Union during the Civil War and, as Ames puts it, “preached his people right into the war.”

Gilead was once a stop on the Underground Railroad. Now, in 1956, at the dawn of the civil rights movement, it is a sleepy, dusty town full of white people, the small black population of the town — Ames still uses the term “Negro” — having been mostly pushed out years ago and the black church burnt down, ostensibly by accident.

Midway through the book, Ames is surprised when Gilead’s prodigal son returns from a 20-year absence: Jack Boughton, whose father is the town’s Presbyterian minister and Ames’s best friend.

Photo by Pete Marovich/Getty Images

Photo by Pete Marovich/Getty ImagesAt first Ames does not trust Jack, but we watch him come to understand him as the book goes on, especially once Jack reveals to Ames that back in Tennessee, where he’s been living for decades, he has a common-law wife and child. They haven’t married legally, because she’s black, and it’s against the law there. Iowa is one of only two states that never had laws against interracial marriage (something Robinson pointed out in an interview with then-President Barack Obama in 2015). So Jack wonders, cautiously, to Ames if he could bring her and their son to Iowa.

Yet for all of their history of tolerance and agitation for the Union’s side in the war, their heritage as a stop on the Underground Railroad, the town of Gilead is not going to be ready for Jack Boughton to bring home his black family. Ames, after thinking about it, tells him as much. Jack, a native of Gilead, knows it already. Even in the “shining star of radicalism” of Iowa, as President Ulysses S. Grant once called it, belief in liberty and belief in equality run along separate rails separated by fear and mistrust.

Robinson returned to Gilead in two subsequent novels, Home and Lila. They’re not sequels. Each retreads the same time period as covered in Gilead, but this time from female perspectives (albeit in the tightly restricted third person). In Home, we see Jack’s return through the eyes of Glory Boughton, his sister, who housekeeps for her father after the disappointing dissolution of her marriage. In Lila, we see it through the eyes of John Ames’s wife, a migrant with a sordid past who never quite feels at home in Gilead, though her husband barely knows.

Through the trio of novels, a fuller picture emerges of Gilead than the one that Ames’s limited vision offers up. It is not just an idyllic stop out on the prairie, or at least not merely that. It’s a place fraught with longings unfulfilled. Gilead is where people keep their loneliness, so often caused by fear, close to the chest.

In Atwood’s Gilead, zealotry has replaced humanity

In this summer’s heat, I have been humming “There is a Balm in Gilead” again because I keep briefly misinterpreting statements I read on the internet about the world being “like Gilead” right now. Nobody means Robinson’s Gilead, Iowa. They mean Atwood’s dystopian Republic of Gilead.

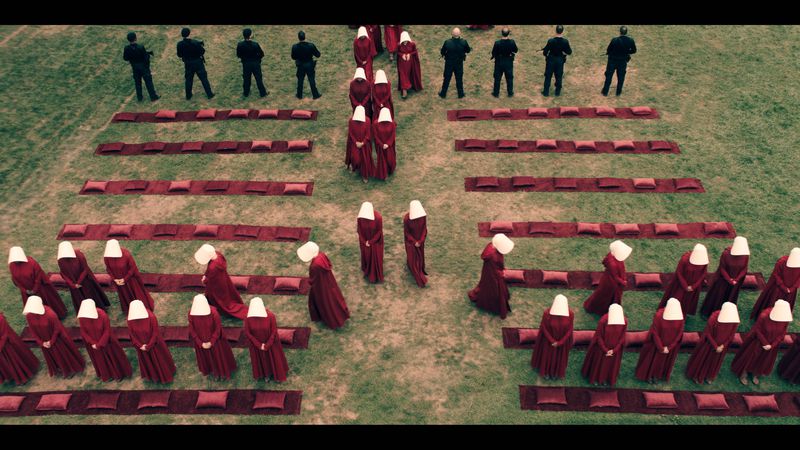

The Gilead of Atwood’s novel does not look like the Gilead of Robinson’s, though they’re both in America. In the near future, the world is suffering from an extreme infertility crisis and facing population depletion, and a group of extremists calling themselves the Sons of Jacob uses this to seize power and institute a strictly stratified regime. Society in the Republic of Gilead is broken into a few different groups, but the most notable from the perspective of the book’s narrator are wives and “handmaids.”

Hulu

HuluIn designating the “handmaids,” the Sons of Jacob are referring to the Bible. In Genesis 30, the barren Rachel begs her husband, the patriarch Jacob, for a child. She gives him her handmaid, Bilhah. “Sleep with her so that she can bear children for me and I too can build a family through her,” she says to Jacob, and he does, eventually taking the handmaid of his other wife, Leah, who is Rachel’s sister. The handmaid’s child is taken from her, to become her mistress’s child.

In Gilead, the main occupation for “handmaids” is to submit to “The Ceremony” — in essence, ritualized rape — and bear a child, who will then be taken from her and given to the Commander (a high-ranking man) and his wife. The residents of Gilead live in fear; all of them do, but the women take the brunt of it, tasked with the responsibility of bearing children and cruelly punished, banished, or killed if they fail to do so, or if they show glimmers of having a mind of their own.

Each handmaid bears her Commander’s name. In the Bible, we at least are given the names of the handmaids who bear children for their mistresses, though they never get to tell their own stories. The narrator of the novel tells hers, but is known only to us as Offred (“of Fred”). The Handmaid’s Tale is her letters to some unknown reader she hopes will someday find them.

There are whisperings of an “Underground Femaleroad,” an escape route north to free Canada, and some kind of white supremacy is behind the actions of the Sons of Jacob. White birth rates are dropping much faster than nonwhite rates, and we catch a whiff in the novel via a glimpsed newscast that the “resettlement of the Children of Ham is continuing on schedule.” This is also a sort-of reference to the Bible, though more to an old, racist theological concept extrapolated by some Christians from the text, used to justify slavery and discrimination against dark-skinned people.

The Handmaid’s Tale TV adaptation has been roundly criticized for its handling of race in Gilead. Critics note that the show’s casting of one black actress as a handmaid makes little sense, particularly if white supremacy is part of the Republic: “The Handmaid’s Tale is a classic example of the problem with settling for diversity that exists out of a desire to be ‘color-blind,’” Angelica Jade Bastien wrote at Vulture.

The show seems sometimes to derive horror by asking the audience how awful it would be if things happened to white women that actually do happen and have happened over centuries of American history to communities of color. Its color-blindness comes across as, at best, tone-deafness.

Which is not wholly unlike Gilead, Iowa. Whether or not the burning of the black church in Gilead was motivated or an accident, it was never rebuilt, and both men know the reason. There is a queasy rationale behind why Jack can’t bring his wife and child home to Gilead.

And even for those who remain in Gilead, a zealotry reigns that has stopped seeing people as human and started seeing them as numbers and cogs, bodies without individual souls. That zealotry requires shame at one’s station and fear of one’s own death to keep others in their place. The handmaids are taught to tattle on one another, and in the Hulu series to “slut-shame” one another, too.

That fear and shame is of a piece with the shame Rachel in the Bible felt because she couldn’t bear a son. It is the same fear that Bilhah must have felt that kept her from rebelling. That same fear is what made it illegal in Tennessee for Jack Boughton to marry the mother of his son, and what made it unwise for him to bring them to Iowa, too.

That same fear quietly pushed the black community out of Gilead, Iowa, altogether, almost without people like John Ames noticing. That sickness of soul calls for the balm that Mahalia Jackson sang about, and so many others before her.

Is there no balm in Gilead?

I suppose the only reasonable way to end a trip to these fictional Gileads is to ask: Well, is there balm in Gilead? Is there any way out of the loneliness and shame and violence of both Robinson’s historical Gilead and Atwood’s future dystopian one? And if so, what is it?

Robinson’s answer might be that the problem is neither place is Puritan enough. That might sound completely ridiculous — but it’s worth thinking about.

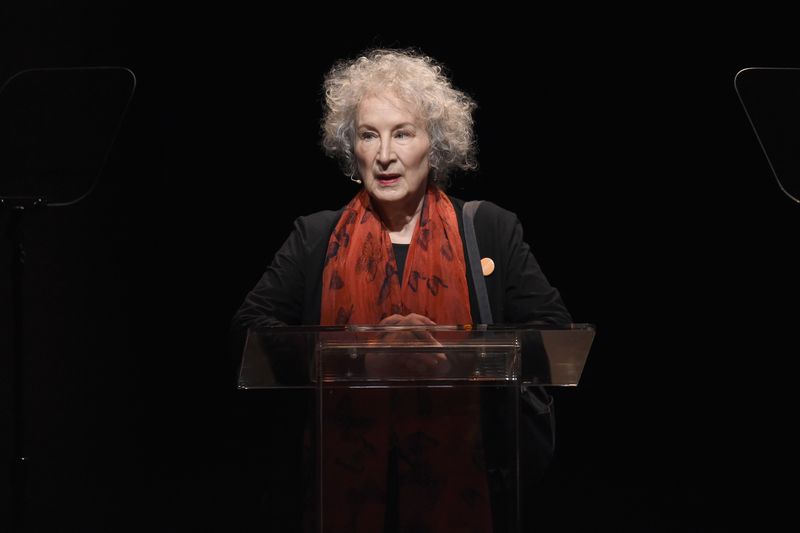

In The Handmaid’s Tale’s 2017 preface, Atwood writes that “the Republic of Gilead is built on a foundation of the seventeenth-century Puritan roots that have always lain beneath the modern-day America we thought we knew.” Later, she clarifies for those who questioned whether the book is against religion that it’s not anti-religion — “It is against the use of religion as a front for tyranny; which is a different thing altogether.”

Hulu

HuluI imagine Robinson taking umbrage at the idea that it is Puritan roots that undergird the Republic of Gilead’s stringent, unyielding, cruel rules. That may be, on the surface, a bit surprising. She is an outspoken and self-proclaimed liberal Protestant who nonetheless in her nonfiction is a formidable interpreter of John Calvin, the theologian whom many associate with dour, strict, condemning Puritanism.

But Robinson’s take on Calvin and the Puritans who were his heirs is at cross-purposes with the popular imagination. “She loathes the complacent idleness whereby contemporary Americans dismiss Puritanism and turn John Calvin, its great proponent, into an obscure, moralizing bigot,” the critic James Wood wrote of Robinson in the New Yorker in 2008.

He quotes her essay “Puritans and Prigs,” in which Robinson describes Calvin’s belief in humanity’s “total depravity” as something much gentler than you might suspect: “the belief that we are all sinners gives us excellent grounds for forgiveness and self-forgiveness, and is kindlier than any expectation that we might be saints, even while it affirms the standards all of us fail to attain.”

Robinson’s nonfiction is at times much more barbed and polemical than her fiction, and she has reserved some harsh criticism for elements in American Christianity — most specifically, fear, particularly in connection with the gun debate. For the New York Review of Books in 2015, she wrote that “fear is not a Christian habit of mind.”

The Puritan tradition, in the Robinsonian imagination, cannot coexist with fundamentalist zealotry or polite bigotry. If one acknowledges that the fallen state of all mankind is a reason to forgive, not condemn, then there’s no basis for either.

And though Gilead, Iowa, is the setting for novels that are fundamentally about grace, it’s not really Puritan enough either, by Robinson’s definition. It is haunted by ghosts, even if its more pious residents wouldn’t put it that way. Its ghosts are American ghosts: praising liberty, but not all of it; fearing the unknown, the stranger, the different, the sojourner, preferring them to keep their voices to themselves. It is a town of hopes deferred and incomplete joy, stories quieted, things left unsaid.

Nicholas Hunt/Getty Images for Tory Burch Foundation

Nicholas Hunt/Getty Images for Tory Burch FoundationMuch discussion around The Handmaid’s Tale has centered on how much Trump’s America resembles Atwood’s Gilead. Perhaps too little of the discussion has also asked how much Trump’s America is like Robinson’s Gilead.

You’d have to be extraordinarily blind to not know that fear is a dominant, if not the dominant, feeling in 2018. Harnessed fear is used by political leaders and the feedback loop they inhabit and stoke. As Kathryn VanArendonk notes, it seems almost preposterous that there’s no constant cable news feed in the TV version of Gilead; indeed, in the final essay of her most recent book, Robinson writes that “my mother lived out the end of her fortunate life in a state of bitterness and panic, never having had the slightest brush with any experience that would confirm her in these emotions, except, of course, Fox News.” It’s the favorite tool of harassers and abusers, of those scared of losing their own station.

We cannot really escape fear. There are reasons to be afraid. But fear wants to keep us from telling our stories and testifying to truth. And so both Gileads need the balm in Gilead, the song of protest and comfort and witness. Gilead can become the “hill of testimony.”In her novel’s 2017 preface, Atwood writes about the “literature of witness,” which I think is her way of suggesting how we might not live in fear. “Offred records her story as best she can; then she hides it, trusting that it may be discovered later, but someone who is free to understand it and share it,” Atwood writes. “This is an act of hope: every recorded story implies a future reader.”

In this divisive climate, in which hate for many groups seems on the rise and scorn for democratic institutions in being expressed by extremists of all stripes, it is a certainty that someone, somewhere — many, I would guess — are writing down what is happening as they themselves are experience it. Or they will remember, and record later, if they can.

That work is done by journalists and musicians, artists and entertainers, writers and critics, and people who tell stories to one another and to their children — all of us in our halting and often-broken ways. But I suppose Robinson’s Calvin has room for grace for those, and Robinson’s novels, with their many characters with many perspectives that sometimes conflict with and contradict one another, suggest that we can all still move further to witnessing the truth if we just keep talking, telling stories, if we do not fear.

The Gileads Robinson and Atwood have given us are testimonies to the past and templates for the future. What we do in the present is our responsibility.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png