“We’ve been living without truth for a long time.” —Michael Eric Dyson

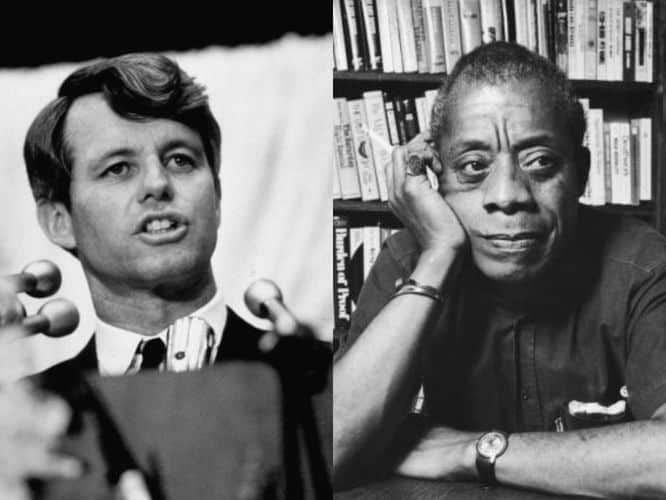

In the spring of 1963, Robert F. Kennedy, the attorney general of the United States, and James Baldwin, the great writer and novelist, met in a penthouse apartment in New York City.

It was supposed to be a friendly conversation about how to improve race relations in America, but it quickly devolved into a bitter fight. Baldwin, and the small group of black artists and intellectuals who joined him, thought Kennedy was ignorant of the black experience and suspected he was trying to exploit them for political gain.

Kennedy, for his part, thought his interlocutors didn’t understand politics or policy, and he walked away convinced that they refused to hear him out. In truth, Kennedy wasn’t prepared for the conversation, and he admitted as much after.

But this famous encounter, and the divisions that drove it, remains as relevant today as it was in 1963. That’s the argument Michael Eric Dyson, a sociologist at Georgetown University, makes in his new book What Truth Sounds Like. For Dyson, the context has changed, but the issues, demands, and injustices haven’t, especially in the age of Donald Trump.

I spoke with Dyson about what happened in that penthouse apartment back in 1963, what a comparable conversation would look like today, and what it will take for America to finally exorcise its racial demons.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

Tell me about the infamous conversation between Robert Kennedy and James Baldwin in 1963. How did it happen? What did they discuss? What went wrong?

Michael Eric Dyson

They had a couple of meetings. The first one was a little breakfast meeting with just the two of them. Basically, Kennedy wanted to know what was up with all this rage in urban America. He sensed a growing desperation in the black community, and he was working behind the scenes with Martin Luther King Jr. and others. But he noticed that for the first time, black people were rebelling violently against what they saw as injustice, particularly in Birmingham, Alabama.

So Kennedy saw what was happening in the South and feared that something was brewing in the North. He wanted to know why black people were so attracted to the black Muslims and various revolutionary movements. He was trying to figure out what the hell was going on.

But Baldwin arrive late for the first meeting because his plane was delayed, and so they only had half an hour. They had a nice conversation, though, and they liked each other. So Kennedy invited Baldwin to meet him the following day at his family’s apartment in New York City, and he told Baldwin to invite other prominent black intellectuals and artists, people Baldwin thought “black people would listen to.”

Sean Illing

So Baldwin, the most famous writer of the day, calls up some of his friends, people like Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne and Lorraine Hansberry, and they go to Kennedy’s apartment to have this dialogue about black rage. What happened?

Michael Eric Dyson

Well, Kennedy shows up wanting to talk about the urban agenda and what the administration should pursue, and of course he wants to know why black people are so attracted to violent radicals and extremists instead of peaceful activists like MLK.

But the meeting went downhill when Jerome Smith, a legendary civil rights activist, erupted in anger because he felt that Kennedy wanted black people to be grateful for what the administration had done and was warning the people in the room that all this black rage was likely to alienate white voters from the Democratic Party. Sound familiar?

Smith told Kennedy, “I’m who you need to worry about, not the black Muslims.” Smith was an acolyte of MLK and Gandhi, and so he had always been peaceful, but he told Kennedy that his patience was running out and that when a person like him decided to pick up a gun, that’s when you really need to be concerned.

This sort of upended the whole meeting. Kennedy looked to Baldwin for help, but Baldwin told him, “There are many distinguished people in this room … but the only man you should be listening to is over there.” And pointed him right back to Jerome Smith. So there was this wall of solidarity that sort of tossed water on Kennedy’s plans.

Sean Illing

And what exactly did they want Kennedy to do?

Michael Eric Dyson

They wanted him to understand the moral dimension of race and not the political one. And they wanted his brother [President John F. Kennedy] to do the same thing.

So, for instance, they asked, “Why doesn’t your brother commit to a powerful symbolic gesture, like escorting black students to school in the face of George Wallace?” But [Robert] Kennedy thought that was pure theater, a ridiculous stunt. He kept telling them that the [Kennedy administration] was working behind the scenes to promote change.

And that was exactly the problem. This was not just about politics; it was about morality, dignity, about taking a symbolic stand in front of the entire country. Kennedy didn’t get that. He kept insisting that change was hard and slow.

At one point, he said, “I’m Irish, my family’s only been here for two generations, and now my brother’s president.” To which Baldwin said, “We’ve been here for five generations and there’s nothing to show for it.”

Sean Illing

The great divide in that room, the divide between the white liberals on the one hand and the black activists on the other, was really about this choice between pragmatism and radicalism, between incrementalism and revolution. And how you view this debate has a lot to do with your position in society and the urgency of your demands.

Michael Eric Dyson

Absolutely. Kennedy saw it as a clash between witness and policy. He said, “Black people want to bear witness to their truth and their pain,” but he assumed that meant they weren’t interested in policy.

That wasn’t true at all. But they saw the limits of focusing on policy without a moral center. Hell, laws were already on the books, but cops were still doing what they were doing to black people. So it was about a lot more than laws and policy.

They felt policy without moral vision and ethical urgency was too abstract. They wanted Kennedy and people like him to understand the personal and existential pain that black people had to bear. They wanted Kennedy to feel that pain that day, that agony and trauma, and he wasn’t ready for it.

Kennedy, to his credit, wasn’t talking merely about incrementalism. He was also talking about voting as a key to black liberation and freedom.

But he wasn’t interested in a revolutionary reorganization of the logic of democracy, and the black people in that room were because they understood that the problem was at the very roots of American democracy, at its founding.

The story of America had to be retold and reexamined with a kind of moral intensity that Kennedy wasn’t prepared to accept.

Sean Illing

How do the problems that were discussed in that apartment in 1963 map onto to the world of 2018?

Michael Eric Dyson

Are we not in the same position — black rage about racial injustice boiling over and white indifference to it? Is patriotism still not defined by a blind obedience to the flag and a willingness to fight wars abroad as opposed to dealing with the injustice that people confront here at home?

Right now the president is trying to cow black athletes into believing and making the rest of America agree that patriotism is measured by standing up during the playing of the national anthem and that kneeling down is a sign of unpatriotic behavior.

Black Lives Matter arose as a result of black rage against injustice by police — people who victimize unarmed black people constantly and relentlessly. These are not unlike the conversations on the agenda in 1963, and yet here we are in 2018 still wrestling with them.

Sean Illing

If a comparable conversation were to take place today, what do you suppose it would look like?

Michael Eric Dyson

In some ways, the conversation is ongoing, and it’s about criminal justice reform and wealth inequality and prison reform and housing disparities and the environment and unequal access to health care and the rights of all minorities and of poor Americans and gay and lesbian citizens. These are all interconnected, and they matter. It’s not just about black Americans.

Sean Illing

Progress has been made, and things are far better than they were in 1963, on almost every level. But the structural issues remain, and the problems have been ameliorated, not resolved. I think it’s worth making that point.

Michael Eric Dyson

No doubt. Things are better now, and we should acknowledge that. At the same time, the persistence of so many problems, particularly the wealth and housing gap, suggests that some of these root problems haven’t been addressed. Martin Luther King Jr. died going to Memphis to defend sanitation workers and we still have people who are desperately poor and who can’t get a decent job or decent health care. So there is still so much work to be done.

Sean Illing

You say that America is always trying to achieve its redemption on the cheap, that the gap between the powerful and the disenfranchised is continually exploited rather than bridged. What will it take, in your estimation, to finally transcend our demons — racial and otherwise?

Michael Eric Dyson

We gotta tell the truth, brother. People think Donald Trump ushered in a new wave of untruthfulness, but I think he just exposed what was already there. We’ve been living without truth for a long time.

We were post-truth in 1619 when we brought 20 people here from Africa claiming that God had sent us over there to redeem their souls and save them from the savagery of Africa. And we’ve been post-truth ever since.

This ain’t the first time a politician has lied and manipulated the facts. What some call progress, native people called genocide. What the Confederates said was a fight for honor and dignity and heritage, we say was a fight for hate. So we’ve always disagreed about the facts of the case and how they should be interpreted.

Donald Trump is treating the entire nation as the nigger. I mean, black people are used to that, and therefore, we are not as outraged or surprised. But we’ve got to deal with the reality that the president is treating America the way black people have been treated in this country from the very beginning.

And we can survive it the way black people always have — through resistance, through introspection, by fighting with our moral beliefs and by insisting that a better tomorrow is possible.

Author: Sean Illing

Read More