Climate provisions and Medicare expansion are just a couple of the issues being debated.

Democrats are pretty optimistic about their budget reconciliation bill, but they’re not quite at an agreement.

“I do think I’ll get a deal,” President Joe Biden said Thursday. “We’re down to four or five issues. … I think we can get there.”

Whether Biden is correct remains to be seen. So far, Democrats aren’t sure what will and won’t be in the bill, or how much it will cost. But, for the first time in weeks, they appear to be making some real progress.

The reconciliation bill is meant to deliver on a key part of President Joe Biden’s agenda: making massive investments in social and climate programs. In response to Republican opposition to this platform, Democrats turned to the budget reconciliation process (which allows legislation to be passed by a simple majority vote) to enact Biden’s agenda.

On Thursday, Biden noted that there are key issues lawmakers still don’t have consensus on, including how to handle Medicare expansion of dental, vision, and hearing coverage; which taxes they’ll use to pay for the bill; and what climate provisions they’ll include to spur a transition to clean energy.

Here’s where the bill stands.

Democrats’ disputes, briefly explained

Democrats hold slim majorities in the House and Senate but have failed to agree on how big the reconciliation package should be and what should be in it. Progressives have pushed for more than a dozen programs and around $3.5 trillion in new spending; moderates have argued for funding fewer programs and for spending closer to $1.5 trillion. In recent weeks, the two groups seemed to be at an impasse.

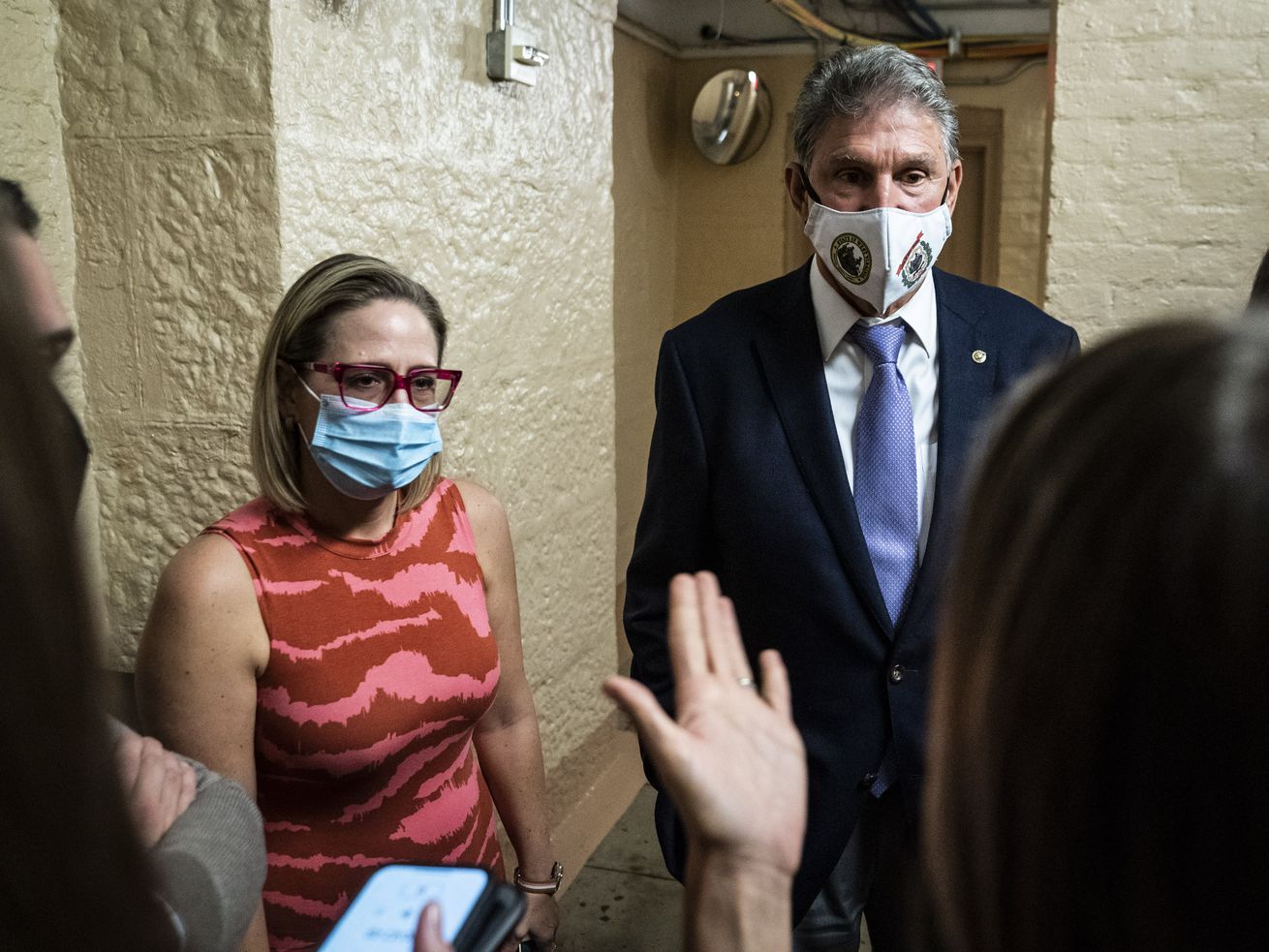

This week, a flurry of White House meetings and negotiations have signaled forward motion. Progressives including Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) finally met with moderate Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) to talk about their positions on Tuesday. And a framework is slowly, if haltingly, coming together.

That said, there’s no final agreement, and no guarantee that Democrats have all the votes they need at this point. Democrats need all 50 of their senators and all but three of their House members to back the legislation.

Earlier this month, Democrats set a tentative deadline of October 31 for the end of their negotiations. So far — despite talks this week — meeting that deadline remains in doubt.

“This is not going to happen anytime soon,” Manchin told CNN on Thursday. “They’re trying to get a meeting of minds to find out what can happen from there.”

What’s holding up the reconciliation negotiations

Negotiations hinge on getting two moderate senators — Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema — on board while making sure any of the cuts and changes they want don’t dilute progressive support.

It’s a tenuous balancing act given how progressive and moderate demands are often in opposition with one another. And though Manchin and Sinema both want a smaller bill, they don’t always agree on what that looks like.

Manchin, for instance, has focused on Medicare expansion, climate provisions, means-testing benefits, and not taking on a lot of debt. He’s won some concessions already. Since Manchin called for the Clean Electricity Performance Program to be stripped out of the bill, it’s more or less been tossed. Expanded Medicare coverage of dental, hearing, and vision also will likely be curtailed significantly due to his opposition.

“Here’s the thing … Mr. Manchin is opposed to that,” Biden said Thursday of the possibility of a Medicare expansion.

It has been less clear what Sinema wants to see changed. However, she has signaled concerns with the proposals to lower prescription drug prices by allowing Medicare to negotiate, a chief priority for the Congressional Progressive Caucus and a source of up to $700 billion in funding for the bill. She’s also expressed opposition to new tax policies intended to cover the costs of the legislation.

Despite recent progress, there’s still a lot to be worked out

The provisions Democrats agree on are also causing delays. While programs including paid family leave and an expanded child tax credit are broadly popular, specifics around their duration and scope have prompted internal debate.

The expanded child tax credit, a recently instituted annual payment of up to $3,600 per child that most families now receive if they have kids 17 or younger, is backed by many Democrats. It could massively cut child poverty, perhaps by as much as 45 percent. But because the benefit would cost roughly $100 billion per year, it may now only be extended for one year.

That shorter time frame has prompted pushback from top Democrats, including House Appropriations Chair Rep. Rosa DeLauro, who’d like to see the policy last for much longer because of the impact it has on addressing poverty rates. On the other end of the spectrum, Manchin has called for access to the child tax credit to be capped based on income, and that work requirements be instituted for those receiving it.

Paid family leave was originally planned to last 12 weeks, but will likely be shortened to four, Biden said Thursday. This could save upward of $300 billion; a four-week benefit that’s expected to last for a shorter period of time has an estimated cost of roughly $100 billion, according to the Washington Post, while the House’s 12-week version was estimated to cost $450 billion to $550 billion over 10 years.

Changes like this have worried progressives, who argue that four weeks simply isn’t enough time for families with a new child or sick family member to get any meaningful benefit from the program. Research has found, for instance, that around six months is the ideal amount of parental leave to promote bonding with children, while ensuring that people who take leave aren’t penalized in the workplace.

Access to both programs could wind up getting capped by income. This is something many progressives are staunchly against, citing data like uptake rates for SNAP, or food aid, that has found means-testing — making beneficiaries prove they qualify for a given program — limit social programs’ effectiveness. Manchin, however, has pushed for more means-testing, arguing that he fears leaving out such requirements will lead to an “entitlement society.”

Manchin’s seeming veto of the Clean Electricity Performance Program has brought new debate on climate issues. While that program is likely to be cut, progressive lawmakers who favored it are struggling to identify other policies, including a suite of tax credits, that could incentivize a similar shift to clean energy.

“We’re looking at emissions reductions … to figure out what would be the most effective ways to replace the CEPP,” CPC Chair Pramila Jayapal said on Thursday. “I don’t believe we’re at a resolution yet.”

Another complication: Lawmakers’ original plans to pay for these programs have been scrambled by Sinema’s concerns about the bill’s tax provisions, including increases to the corporate tax rate and the top capital gains rate. It seems they’ve been able to find some workarounds like a tax on billionaires’ wealth, a minimum corporate tax rate, more aggressive IRS enforcement, and a 2 percent tax on stock buybacks, Roll Call reports. These provisions, however, are all tentative.

“The bill will be fully paid for and the matter is in the hands of our chairs of the Finance Committee and the Ways and Means Committee,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said Thursday.

Democrats want to get something done by the end of the month

Democrats’ goal is still to reach a deal on something by October 31. It’s unlikely that agreement will be full-fledged legislation, though it is expected to be a framework that includes a top-line figure as well as the main policy provisions.

And Democrats face a lot of pressure to meet that self-imposed deadline.

The moderate wing of the party was promised a September vote on a bill full of their priorities that never came to pass because progressives pushed for that vote to accompany one on reconciliation. Because the second wasn’t ready, the first didn’t happen. Moderates weren’t happy about that, and they want a vote on their bill as soon as possible. For that to happen, at the very least, there needs to be a reconciliation framework.

Biden has emphasized, too, that he’d like a concrete deal he could take with him when he joins the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow at the end of the month. “The prestige of the United States is on the line,” he’s reportedly told lawmakers. And Democrats are eager to get a win ahead of the November 2 gubernatorial election in Virginia, believing that would help their chances in what polls suggest is a tight race.

On December 3, Congress will be facing a government shutdown and a credit default that could severely wound the global economy. Avoiding these things will require passing a spending bill and raising the debt limit. Doing that — or passing legislation to give themselves more time to do that — has historically taken lawmakers some time. And they don’t have much: There’s only a little more than a month left on the legislative calendar this year.

That timing gives Democrats roughly one more week to deal with their differences on reconciliation and get to a proposal that moderate senators and progressive House members can live with. “We’re working very hard on rolling up our sleeves,” Schumer told reporters Thursday.

Author: Li Zhou

Read More