As unemployment soars, the WPA’s emphasis on artists shows a path toward recovery.

In the 1930s, as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and its Works Progress Administration effort, the federal government hired more than 10,000 artists to create works of art across the country, in a wide variety of forms — murals, theater, fine arts, music, writing, design, and more. It was part of a plan to stimulate economic recovery, for a country reeling from the Great Depression, widespread poverty, and high unemployment.

But it was also much more than that. Sandwiched between the World Wars, the arts projects overseen by the WPA — which included the Federal Art Project (focused on the fine arts) as well as initiatives in other disciplines — were meant to help the United States develop its own distinct style of art-making. This was especially important in the midst of a historical moment where rising tides of nationalism in other parts of the world were leading governments (run by figures like Stalin and Hitler) to direct and control artworks that would project their own ideological frameworks to their citizens and the world.

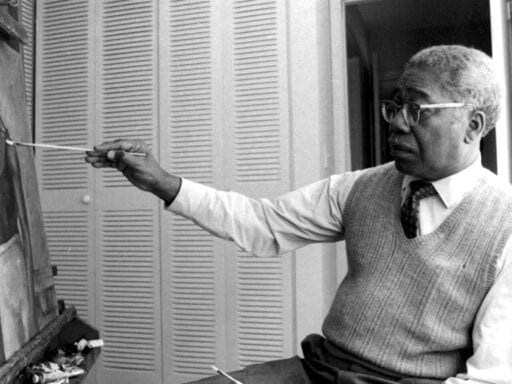

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20041736/GettyImages_466684093.jpg) Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany of the WPA artists — like Dorothea Lange, Jackson Pollock, Walker Evans, Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, and thousands of others — produced iconic work that captures the American experience at the time. Others made less famous work that nonetheless became part of community life, since the WPA’s focus was on creating public works of art and fostering arts education throughout the nation.

In some ways, 2020 feels a lot like 1935 — US unemployment is high, a recession looms, and there’s a need for communities to pull together. And thus I became curious about how the Federal Art Project and other similar initiatives worked, what kind of restrictions and freedoms the artists had, and whether such a program might work today. So I called Jody Patterson, the Roy Lichtenstein chair of art history and an associate professor at Ohio State University, to ask. Patterson is the author of the forthcoming book Modernism for the Masses: Painters, Politics, and Public Murals in 1930s New York from Yale University Press, and studies the interaction of art and politics in 20th-century American art. We talked about the origins of the WPA arts program, the role of public art, and how shifting ideas about the purpose and meaning of art might affect any efforts to start a new federal arts program today.

Alissa Wilkinson

How did the Federal Art Project and related arts projects come about?

Jody Patterson

One thing to bear in mind is that the Federal Art Project was a part of a much bigger and broader initiative: the WPA, the Works Progress Administration, which was a very visible project — pump-priming, keeping the unemployed [working], maintaining their skills, putting them back to work. This included everything, like building dams and bridges and roads.

What’s so unique about Roosevelt’s vision was he included culture in those provisions. That the arts were part of a much larger New Deal for the American public — a testament to “the more abundant life” he kept emphasizing in the midst of the Great Depression — is really key.

The Federal Art Project was part of something called Federal One, which had projects not just for the fine arts but also for theater, for writing, for music. There was a design index. It was one aspect of a really diverse and wide-ranging kind of project.

Another thing that’s important to bear in mind: Art production, art reception, audiences, patronage, galleries, museums — all of that had really been centered in a handful of urban centers like New York and Los Angeles, as it continues to be today. The Federal Art Project took on the whole nation as part of the project. It brought exhibitions, educational centers, and art lessons across regions that had not been well-served, and into communities that had very much been disenfranchised from culture.

So in addition to traveling exhibitions, one of the really key aspects of the Federal Art Project was the community art centers. In communities such as Harlem or the South Side of Chicago, unprecedented opportunities opened up for African American artists. We don’t even have a program like that today.

As far as its genesis, there are three things to keep in mind.

The first is that [today,] the US might well reach levels of employment not seen since the 1930s, or even worse than the ’30s. In the ’30s, the government saw it as an obligation, part of its duty, to provide artists in need with economic support. So they commissioned them to produce public art. That obligation is something we certainly don’t see within the current administration.

In addition to that, there was a very visible precedent for this in Mexico. The Mexican government got behind the Mexican mural movement — funded it and supported it for many years. It was very much a morale-boosting, nation-building kind of initiative. After the Mexican revolution, Mexico needed to find a way of creating a shared history; during the 1930s, the US government saw a benefit in culture’s ability to not just create and contribute to the development of community identity, but to national identity — a truly American art.

That’s related to the politicization of art internationally during the period. We saw all different kinds of states, from communist states to fascist states to the American democratic states, using art as a way to create consensus, build support for its policies, and make its own political platform and view of society visible to a broad, diverse mass audience. There was a real interest in populism across the political spectrum at the time. Roosevelt and the New Deal were throwing their lot in with other nations who were very much doing the same thing, but to different ends.

Alissa Wilkinson

So how did they select which artists to hire?

Jody Patterson

So here, again, it’s really important to differentiate between the Federal Art Project and what was known as the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, and which was much more about hiring well-known, established artists who could produce “quality artworks.” So there were competitions for the Treasury Sections, and most of those arts — murals and public sculptures being the most visible — were put into federal buildings.

In terms of the more widespread mandate of the Federal Art Project: That was a relief project. That was about providing work for unemployed artists. It was means-tested, and it was not dependent upon technical skill and quality. Of course, there was an interest in the aesthetics and style. But it was much more open to stylistic diversity.

There were only two caveats: You couldn’t produce a nude, and you couldn’t address political issues in a direct way. The line between art and propaganda is a really messy one, but you couldn’t outright address political issues or produce nudes.

Nothing is perfect, so there were some issues around freedom of expression and censorship. The Federal Art Project employed over 10,000 artists across the country, and sought to bring art to the broadest public possible. So those works that became the collection of the American people had to be put in public collections — hospitals, schools, post offices, housing projects, that sort of thing — ensuring they were part of communities.

That was very different from Treasury Section; artists took a lot of issues with the more elitist policies of the Treasury.

Alissa Wilkinson

Thinking about this from where we sit in 2020, I’m struck by what a different world the 1930s seem to have been. It’s hard to imagine a world where you could hire 10,000 artists, give them artistic freedom, tell them not to address political issues, and assume that’s a thing that is even possible. Today, most everything has been forced through a political lens, by which we usually mean a partisan lens. Were there battles back then, too?

Jody Patterson

It’s not as if it was just universally accepted; that would suppose a top-down model. Much of the gains and the benefits of the Federal Art Project came through the organization of artists through, for example, the Artists’ Union. Their ability to still engage a variety of styles and a variety of subject matters was something that they fought for and defended. Especially, as you can imagine, in the face of Hitler’s “degenerate art,” his complete antagonism to modernism. It was the same thing with Stalin after 1934, when only socialist realism was a sanctioned form of art.

Artists maintained their agency, in the sense of being able to create narratives or use forms and styles that weren’t overtly political in nature. So you couldn’t engage in politically partisan iconography and imagery, but of course, artists understood in ways that perhaps aren’t as explicit now that all art is grounded in social and economic and historical experience. All art, even the most seemingly abstract, non-objective work, is still ideological. And that was understood in ways that I don’t think we necessarily make as explicit [today].

All art is political, and they knew that, which means you didn’t have to make an overt statement to understand that it had meaning within communities and for different audiences. Style, form, color, figuration — all of these things were part and parcel of the moment in which that art was produced and received. Artists understood that in really interesting ways, and so there was a bottom-up ability to make creative use of the strictures that were in place around not-overt politics and no nudes.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20041784/GettyImages_50336384.jpg) Martha Holmes/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Martha Holmes/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesAlissa Wilkinson

So at the time, artists benefit from getting paid and having employment at a time of very high unemployment. Were there additional benefits for them? And how did the communities respond who were suddenly seeing this influx of art?

Jody Patterson

Yes, artists were able to make work. They were given studio spaces, materials, a living wage — but also, they had an audience, and that is really key.

Art is part of a dialogue. You often have work sitting in a studio, or in a gallery, or hung above somebody’s mantelpiece, but it doesn’t have public reception. These artworks had a built-in expectation that they’d have an audience. They were going to be put out into public spaces. That was really important.

Also, there was a sense of community. Artists were often meeting together, not just in some of the spaces that had been set up in terms of studios and collecting paychecks, but at union meetings. There was a social scene. Artists were removed from the isolation and alienation of the ivory tower, intermingling and interacting, having discussions.

For example, the well-known New York School artist Willem de Kooning has noted time and time again that [being part of] the WPA’s arts projects were the first time that he was able to think of himself as an artist. It wasn’t a hobby. It wasn’t something that he did in his spare time — because, of course, artists always had to do other things, they always had other jobs, had to teach. Now we could think of the artist as a worker, as a professional, and as someone who was able to make an important and significant contribution to American life.

That’s not always the case now. Artists often struggle with identifying themselves as such, and being identified and supported and acknowledged as such.

Alissa Wilkinson

Right. It feels like that’s not the way Americans think about “productivity.” Art isn’t productive unless it makes a lot of money, like Hollywood movies, or is decorative in some way. Often the arts are the first on the chopping block from public budgets because they are “extra.” But it’s not that way everywhere in the world. Would it be fair to say that in the 1930s, we saw the arts in a way that we might associate now with more of a European framework? And was that part of a continuum of American thought, or was it an unusual moment?

Jody Patterson

No, it was unusual. What the New Deal enabled, not only in terms of its rhetoric but also in terms of actual funding, was an alternate economy of the arts. It shifted the social and economic bases for culture away from a market-driven luxury commodity.

The arts before the New Deal — and, with a few exceptions, after the New Deal — have relied on private patronage and the philanthropy of wealthy and elite institutions: galleries, museums, dealers. There was a real transformation in the fundamental economics and social understanding of the value of art. It wasn’t a luxury good. It was seen as an essential part of what constituted a democracy.

The arts, for Roosevelt and the New Dealers, were seen as a fundamental component of a truly democratic society. A democracy could not call itself as such without art, music, theater, poetry, writing, design, photography, film.

So for Roosevelt, this was the American way of life, this richness of experience, and accessibility to culture was the kind of democracy that he was fostering. Of course, the Federal Art Project itself began around 1935 and its activities were concluded by 1943, when the US shifted to a war economy.

In the 1970s, from 1973 to 1980, another initiative drew on the model and inspiration of the New Deal: the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act. It was signed into law by Richard Nixon, and it wasn’t designed specifically for artists — again, it was part of a broader initiative — but it ended up hiring and supporting more than 10,000 artists, which was equal to that of the Federal Art Project. It lasted through two Republican administrations and one Democratic administration, and there’s not nearly as much emphasis on that as a historical case study. It’s often overlooked. But certainly that took on board some of the lessons and legacies of the Federal Art Project. And it was important, in terms of the community work that it did, in the fostering of the idea of a democratization of culture. It wasn’t limited to a few urban centers, but unrolled across the nation in communities that were very badly served in culture at large.

There are [nongovernmental] projects like this too. Right now, the Back to the Streets campaign aims to create 1,000 murals by 1,000 artists in 100 cities on public walls that are offered up by business and property owners. They acknowledge that they are looking back to the example of the New Deal — and, of course, public murals were always the most visible of the initiatives. That’s going directly back to the philosophy underpinning the New Deal, which was John Dewey’s Art as Experience. It was published in 1934 and really had a huge impact on how culture was embraced and engaged with and supported during the ’30s. And that’s happening right now!

I don’t think in the current climate we could ever replicate the New Deal Federal Art Project, and in some ways there are other models that would be more desirable.

I would suggest that maybe amongst the key problems that we would face with any reincarnation of the New Deal in the present context — aside from the antagonism of the Trump administration toward culture — is that our contemporary concept of art is so different from what it was in the 1930s. We have an immensely more complex idea of what constitutes “the public” now. The concept of “the public,” in terms of racial equality, sex, gender, ethnicity, all of these kinds of things, is unfolding.

And we have a far more contested notion of “the state,” the federal state, now compared to then. For example, the idea of federal intervention is completely unwelcome by any Republican administration. Art is seen as either elitist or just not the business of government, in the sense that it’s not something the government should get involved with.

So trying to replicate the New Deal arts projects would be very difficult. But the fundamental transformation of the social and economic faces of art still has so much resonance, and I suspect that’s why we’re having this conversation. The idea of a more public-facing art, and a broader concept of what “art” and what “the public” are, remains incredibly appealing.

I think that any efforts that we make to reexamine history necessarily and significantly have to become a commentary on contemporary problems as well. So surely that’s something that can give us a bit of hope.

Alissa Wilkinson

I’ve talked to people in the past about the National Endowment of the Arts, and why they advocate for the organization to exist as a government agency at all. One thing people have noted to me is that the arts create “pathways” along which art, commerce, and people can travel. Not funding individual artworks so much as structures and institutions where creativity and innovation in art between and among various communities can flourish. How do you think about that? And what could happen today?

Jody Patterson

First off, I’m a historian, not a government administrator. I should also note that I’m not American; I’m Canadian. So when I comment on American political and economic policy, I’m doing it as a noncitizen.

But in some ways, I’m trying to educate and transform the notion of who artists are and what art is, in order to broaden that idea. In addition to creating individual works of art, which the New Deal did and the NEA does, they found ways of building and diversifying audiences, through moving into various regions with programs — educational programs, exhibition programs. That’s where I’m seeing a link to this notion of traveling, creating these opportunities and openings to experience art as a part of everyday life. This cultivates a much broader definition of what art is and what the artist does, and an enfranchisement amongst a much more varied and inclusive population.

It’s important we think of art not as an inert material thing, but as a community resource.

Alissa Wilkinson

It’s been interesting, while people are cooped up at home during a pandemic, to see how art has very quickly taken on an important role in connecting physically isolated people to a community. I’ve watched live theatrical productions on Zoom and seen how people respond to them, or noticed that filmmakers have made their movies available for free, with the idea of starting a conversation or creating a community.

Jody Patterson

Yes! Exactly that. We need to think about who has had the power to define what art is and who an artist is, and to really think about that, again, from a more bottom-up grassroots perspective than from a top-down, market-driven one.

Alissa Wilkinson

It’s been interesting to see distributors put their films related to issues like policing, race, and the Black Lives Matter movement online for free during the Black Lives Matter protests. It’s almost a shift in the valuation of them as works of art.

Jody Patterson

Yes, exactly. Again, “value” is not some objective fact. It’s determined by people and for people. And so to shift who gets to decide what’s valuable — if that’s a legacy of our current experience, that would be remarkable, and really welcome.

I’m in Columbus, Ohio, and through the demonstrations and protests, all these boards have gone up. Many of the main thoroughfares in the city are all boarded up. Almost immediately, the Greater Columbus Arts Council saw the need to provide support for artists, and an opportunity to reach an audience that wouldn’t necessarily feel welcome in a museum. Museums and galleries are closed anyway, so the art we encounter is now out on the street.

After the downtown protest, over 400 artists in the last week have been given funds to go and paint the boarding. Some of the most interesting mural painting I’ve seen outside of Mexico — and I’ve also spent time in Belfast, where murals are part of an everyday experience, both in terms of the aesthetics but also absolutely pointed comment on politics — we have that happening. I’m sure it’s happening in other places.

To take the opportunity to turn these boardings into something that can generate conversation and community response, and to put art right there on every street in the city — it’s a peaceful outlet to voice support for Black Lives Matter, and it’s a place for commentary but in aesthetic terms, using form and color and shape and figures and text. That’s a kind of different approach to share knowledge and information and ideas.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More