One tech company has created a slate of scripted influencers, each with their own storylines. But how is anyone supposed to tell the difference between what’s real and what isn’t?

In June, the UK tabloid the Mirror published a story about a TikTok video that discussed “the four biggest dating app red flags,” according to a creator named @sydneyplus, who said she worked at a dating site. Said red flags include standing in front of a fancy car (likely not their own), describing oneself as an “entrepreneur,” or being weirdly obsessed with their mom. The article is a typical hastily written web post capitalizing on trending content in order to drive pageviews, and was later picked up by the New York Post. The only problem was that @sydneyplus doesn’t work at a dating site, because @sydneyplus doesn’t really exist.

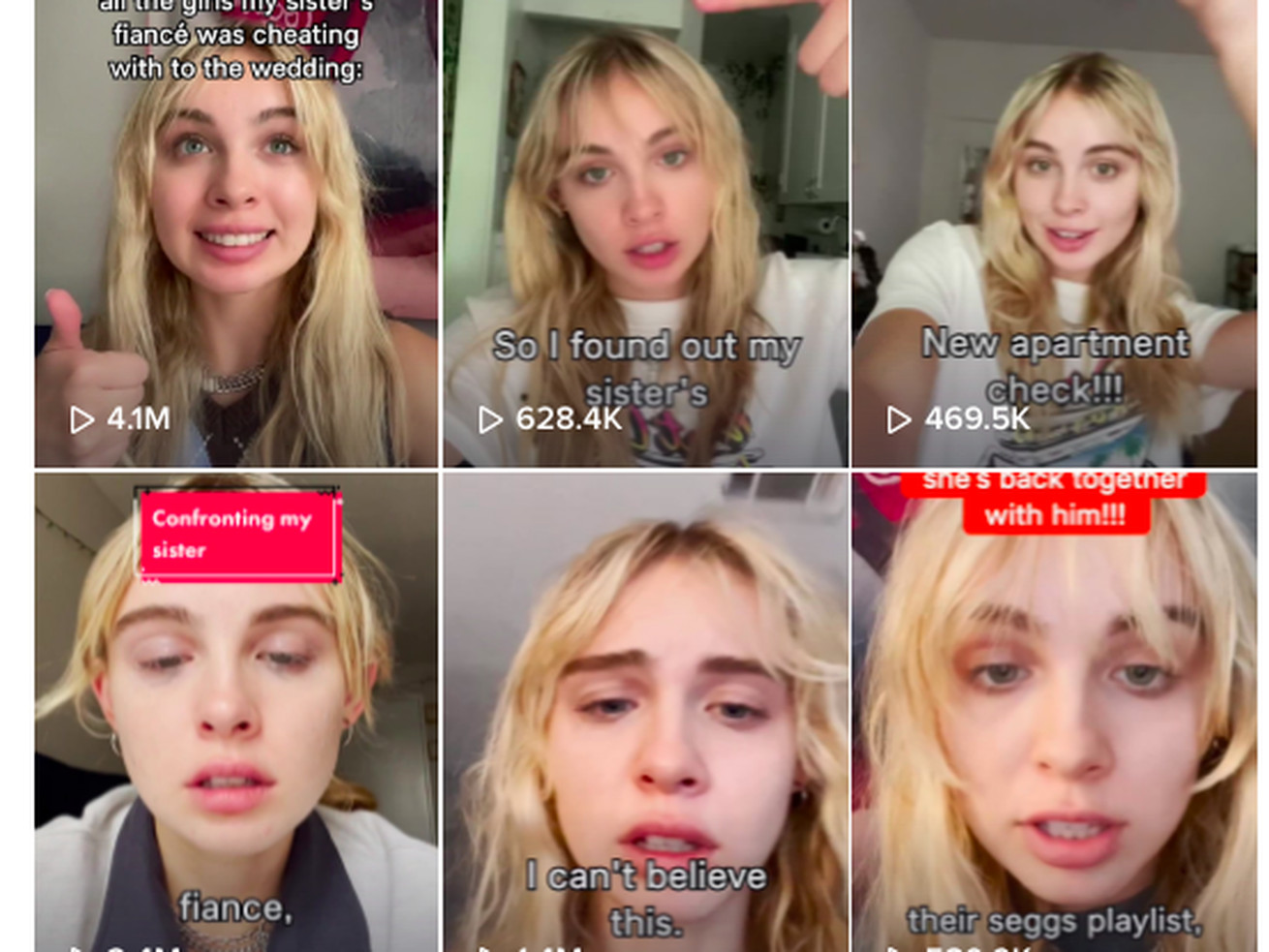

“Sydney,” a broke, blonde 20-something who lives on her sister’s couch and works in customer service at a dating site, is the invention of a team of writers, one actress, and a technology/entertainment/media company called FourFront. Co-founded by a former screenwriter named Ilan Benjamin, the company has so far launched 22 “stories,” or character arcs, eight of them ongoing since the spring. Sydney’s “story,” for example, was that she found out that her sister’s fiancé was cheating, while Ollie, a trans man, discovers that his father also transitioned.

“We’re basically creating an MCU-style universe of characters on TikTok,” says Benjamin. “Some succeed, some fail — it’s the TV pilot season model where we only invest in those that get traction and audiences love.” The company says it’s raised $1.5 million in seed funding so far.

@sydneyplus Public service announcement ‼️Any big ones missing? #foryou #fypシ #dating #datingapps

Last week, Sydney, Ollie, and the rest of the characters — Tia, who discovers her boyfriend is African royalty; Carmen, a self-described sugar baby and bimbo; Chris, a father and Army veteran; and “Billy Hundos,” a “finance fuckboy,” among others — convened IRL in Los Angeles, ostensibly to participate in a contest to win a billion dollars. This also acted as FourFront’s “big reveal,” in which the characters hosted a live Zoom event and showed that they all exist within a single universe. In total, the characters have a combined 1.9 million followers and 281 million views.

Fictional influencers are not unique to the TikTok era. In June 2006, a soft-spoken 16-year-old named Bree began uploading video confessionals to YouTube under the username Lonelygirl15. Bree, however, was actually the invention of screenwriters Miles Beckett and Mesh Flinders, along with their lawyer-producer friend Greg Goodfried. (Interestingly, Goodfried is now the president of D’Amelio Family Enterprises, the company representing TikTokers Charli and Dixie D’Amelio.) Within months, millions of people tuned in, many turning to message boards to speculate about what was going on behind the scenes, and by September, sleuths had found trademark applications and pictures of the actress Jessica Rose, who played Bree. Some fans said they were “heartbroken” by the discovery, but the videos went on to air for another two years. Asked whether something like Lonelygirl15 could exist today, Flinders told the Guardian, “On YouTube now we wouldn’t get away with this for 30 seconds. People would know she’s fake immediately.”

But perhaps that’s less true for TikTok. While FourFront is adamant that most of its audience is aware that what they’re watching is the work of actors and writers, that’s nearly impossible to know for certain. “With everything that happened with QAnon and how alternate reality games have been weaponized, it’s important that we made our universe light and playful — no cult content, no dark content, and every one of our characters is openly fictional,” Benjamin says. Yet nearly all of the comments appear to engage with the characters just like they would with real TikTokers, giving advice and sharing reactions or their own experiences. Though FourFront has started using the hashtag #fictional on its videos and the word “fictional” in the characters’ bios, to expect that users who come across one of their videos on their For You page to put the clues together is asking quite a lot, considering most TikTokers use unrelated hashtags in their posts to gain more traction and choose intentionally weird bios to set themselves apart.

As a commercial rather than purely artistic venture, FourFront told Fast Company that its long-term revenue plan is to license their AI character voices to other companies, and to make money with some kind of subscription model or by selling tickets to live events starring their characters. “Why can’t I hang out with Harry Potter?” he said. “That’s the question this whole company began with: Why can’t we allow people to get closer to their favorite characters?”

@thatsthetia yeah so um…any tips on how to handle this?? #boyfriends #blackqueen #royal #BombPopAwards #helpme

The company also encourages its most invested followers to text their favorite characters on a separate messaging app and “unlock secrets,” using the AI language GPT-3 to respond. With an earlier character Paige, whose story concept was “all my friends blocked me!,” Benjamin says that when they told audiences at the beginning of the messaging session that it was a fictional story, 89 percent wanted to continue, and 42 percent “shared really intimate emotional data with the character.” (Benjamin says they do not plan to sell that data, but instead use it to improve their own storytelling.)

Those characters, by the way, are conceptualized and written by Benjamin and a team of writers, mostly recent grads from USC’s screenwriting program. Ollie’s bio describes him as “made with love by (rainbow flag emoji) actors and creators,” while Chris’s says “made by veteran actors and creators.” Actors, who film and direct themselves and then send footage to an editor, also contribute to the storylines. Cameisha Cotton, who plays Tia, says the idea was pitched to her agent in February as a web series, and that she’d done augmented reality projects beforehand. “They’re incredibly collaborative,” she says. “It’s the coolest SAG project I’ve ever been able to be a part of.”

FourFront is part of a larger wave of tech startups devoted to, as aspiring Zuckerbergs like to say, building the metaverse, which can loosely be defined as “the internet” but is more specifically the interconnected, augmented reality virtual space that real people share. It’s an undoubtedly intriguing concept for people with a stake in the future of technology and entertainment, which is to say, the entirety of culture. It’s also a bit of an ethical minefield: Isn’t the internet already full of enough real-seeming content that is a) not real and b) ultimately an effort to make money? Are the characters exploiting the sympathies of well-meaning or media illiterate audiences? Maybe!

On the other hand, there’s something sort of darkly refreshing about an influencer “openly” being created by a room of professional writers whose job is to create the most likable and interesting social media users possible. Influencers already have to walk the delicate line between aspirational and inauthentic, to attract new followers without alienating existing fans, to use their voice for change while remaining “brand-safe.” The job has always been a performance; it’s just that now that performance can be convincingly replicated by a team of writers and a willing actor.

“We’re telling stories that are a little bit larger than life, and I think a lot of influencers on TikTok do the same thing,” Benjamin says. It’s true — determining whether viral TikTok videos are “real” or created in earnest rather than ironically is the platform’s favorite sport. Tons of TikTokers play a character, to dramatic or comedic or aesthetic effect, but far fewer actually create a detailed narrative arc. If people really want to know whether someone like Sydney, Tia, or “Billy Hundos” is real, it’s not immensely difficult to figure out. But they fooled at least two newspapers, and if one of their videos came across my For You page, they probably would have fooled me, too. It almost feels like benevolent trolling, a nicer version of, say, a tweet designed to provoke outrage but really only ends up driving engagement to that person’s page. You sort of feel foolish taking the bait, but the internet is full of bizarre characters. How is anyone supposed to tell the difference?

This column was first published in The Goods newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one, plus get newsletter exclusives.

Author: Rebecca Jennings

Read More