A new UN interactive atlas reveals how climate change will shape weather around the world.

Humans have warmed the planet by an average of 1.2 degrees Celsius since industrialization began in the 19th century. This small-sounding change has helped fuel severe wildfires, record-breaking heatwaves, floods, and an ever-growing list of other disasters.

What’s worrying is that Earth will continue to heat up — likely past 1.5 degrees — even if humans slash fossil fuel emissions immediately, according to a landmark UN climate report released this week. So does that mean weather will get worse, too?

Now you can see for yourself. This week, alongside its report, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) launched a new mapping tool that shows how weather around the world will change under different greenhouse gas emissions scenarios.

While the IPCC Interactive Atlas didn’t get as much attention as harrowing news stories about the report itself, it’s a striking tool that projects regional temperature, rainfall, snowfall, and even sea level rise. It’s powered by the same models that produced data for the report, and represents some of the best climate science out there in visual form.

The technology behind the map is impressive, too. The atlas took three years to make and “over 1.5 million hours of computing time” on a supercomputer, according to Juan José Sáenz de la Torre, a spokesperson for Predictia, the company that helped build the atlas.

The map tries to strike a balance between the simplicity of, say, Google Maps, and a highly specialized scientific tool. The IPCC has received feedback that it’s “too dorky,” so it may update the user interface, said Linda Mearns, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who was involved in developing the tool. At the same time, its features might be too limited for the most sophisticated users, said Michael E. Mann, a professor of atmospheric science at Pennsylvania State University. The atlas doesn’t, for example, display data on the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like fires and floods.

Nonetheless, it’s a major step beyond the static graphics in the IPCC report. And once you get a hang of it, you can clearly see the disastrous impact of climate change on every corner of the planet — from rising temperatures to rising seas — if countries and fossil fuel companies don’t quickly cut their carbon footprint.

Here’s how to use the atlas, and some of the insights it reveals.

How to use the IPCC atlas

The basics

- Go to this website, and click on the box “regional information.” That will take you to the map.

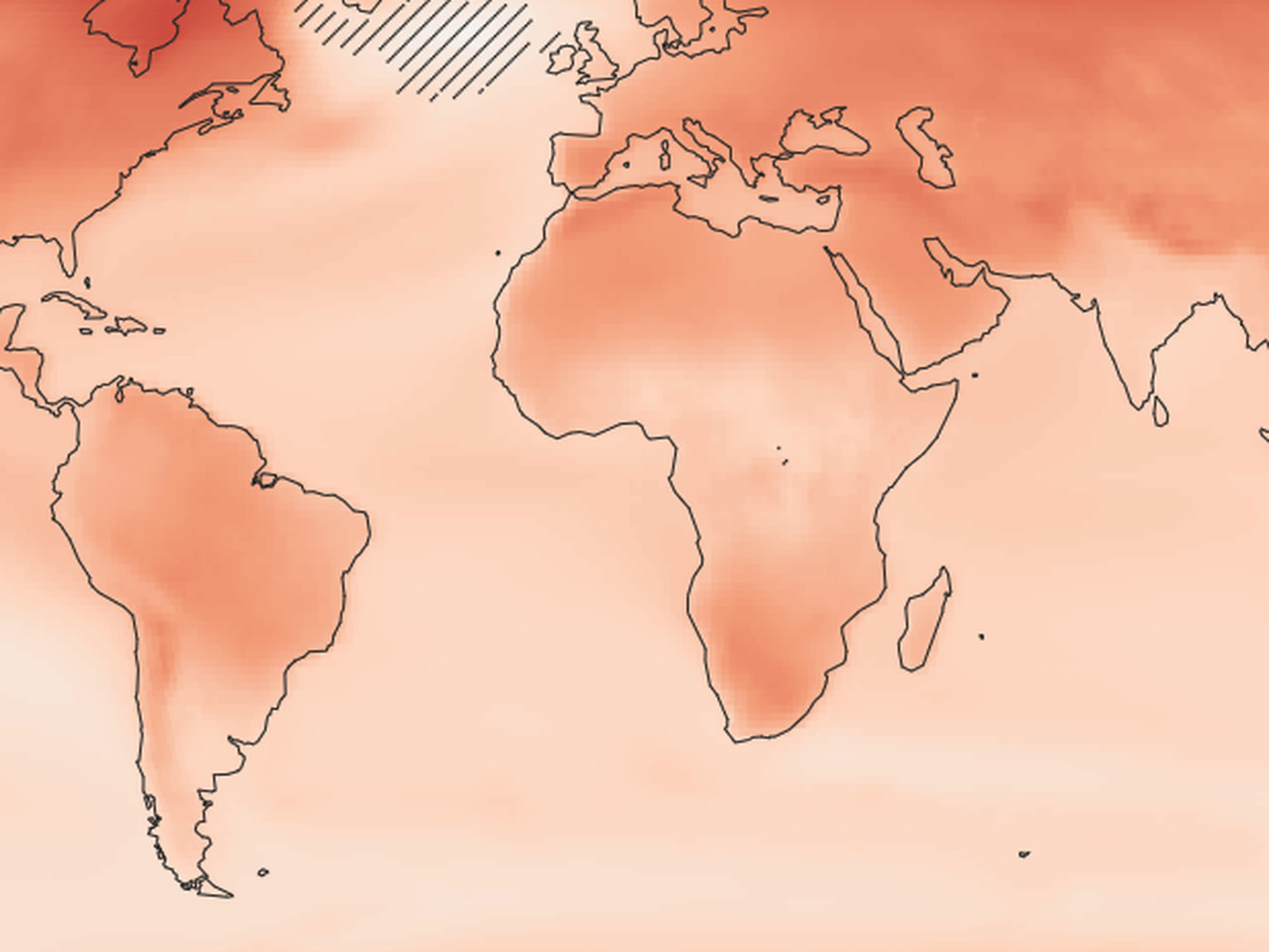

- By default, you’ll see the world under an average of 2°C of warming, compared to a historical baseline (1850 to 1990). You’ll notice that the Arctic and the American West, for example, are darker shades of red, indicating that they’re likely to warm faster than other areas under this scenario.

- From there, you have a lot of different features to play with. Check out the tab “variable,” which allows you to choose what appears on the map — change in average temperature, precipitation, snowfall, and so on. You can also select sea level rise and other ocean variables.

- To lay out different climate scenarios, you can use the tab “value and period.” Again, the default is a world under 2°C of warming, but to factor in the possibility that humans will drastically reduce their emissions (or not), you can change it to 1.5, 3, or 4°C. You can also set the scenario according to a time period (such as 2081 to 2100) under one of four greenhouse gas emissions scenarios laid out in the IPCC report.

- If you want more regional information — such as to see what’s happening in the Western US — there are a few things you can do beyond zooming in. First, under the “dataset” tab, choose a “CORDEX” for whatever area you’re interested in (such as CORDEX North America). CORDEX models are more accurate on a regional scale than the default model, which is global. Then click on a specific region and a window will appear at the bottom of the map, with all kinds of information for that area.

Other neat features

There are a few additional features worth pointing out, such as the side-by-side function, which shows two different climate scenarios next to each other on a map. For example, you can compare the likely change in rainfall under 1.5 vs. 3°C of warming. To use this feature, click the “duplicate map” button on the right-hand side of the screen.

There’s also a neat graphing tool called seasonal stripes, which breaks down weather and climate changes by season. You can find this feature by clicking a region and selecting the “seasonal stripes” tab. (The tab to the left of it is neat, too. Each row represents the results of a different model.)

Lastly, check out the “point information” button on the right side of the map. It allows you to get information on whatever variable you’ve selected by just clicking anywhere on the atlas. There are a lot of other features, which you can learn about here.

What the map tells us about our future climate

The IPCC report reveals in new detail just how connected extreme weather and climate change really are. The chance of intense heatwaves, torrential rainfall, and drought is likely to increase with each degree the planet warms, the authors wrote.

Consider the American West. It will become much, much warmer as global temperatures rise, the map shows. It’s becoming drier, too, Mearns said, and together those changes increase the risk of severe wildfires.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22774980/california.png) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeThe graphic above shows the continental US under 1.5, 2, 3, and 4°C of warming. Red indicates the change in the average daily maximum temperature, relative to a historical baseline.

If you’re looking at warming under different emissions scenarios, it’s also hard to ignore the deep red hues in the Arctic. Temperatures there are rising about three times faster than average global warming, the IPCC report finds.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22775725/Screen_Shot_2021_08_11_at_7.45.55_AM.png) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeAll that warming is shrinking Arctic ice, as you might expect. Alarmingly, the Arctic is likely to be “practically ice-free” at least once before 2050 (in the month of September) even under the least-dire emissions scenarios, according to the IPCC report.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22775722/Screen_Shot_2021_08_11_at_7.44.53_AM.png) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeThe map also shows expected decreases in rainfall. The Mediterranean, for example, is set to get much drier by the end of the century under the high-emissions scenario — especially in the summer — as you can see from the seasonal stripes chart below. Darker colors indicate less rainfall.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22774635/Screen_Shot_2021_08_10_at_3.53.32_PM.png) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeParts of West Asia, on the other hand, including Saudi Arabia and Iran, will likely get much wetter, according to the CORDEX model for the region. (The global model suggests north-central Africa will get more rainfall, too.)

Different emissions paths lead to drastically different outcomes

One thing that’s so useful about the IPCC atlas is that it demonstrates what happens if humans — especially governments and fossil-fuel producers, such as oil and gas companies — fail to cut carbon emissions.

The two maps below show the change in very hot days (above 35°C, or 95 degrees Fahrenheit). The one on top is a world where we cut carbon emissions relatively quickly, and the one below shows a high-emissions scenario. The darker the red, the more hot days.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22774959/Untitled_collage2.png) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeThis shows that while temperatures will rise even under low-emissions scenarios, they could be a lot worse if emissions continue to climb. And pretty much every variable you plug in shows similarly stunning contrasts under high- and low-emissions scenarios, such as these maps of sea-level rise. Similar to the graphics above, the top and bottom maps show low- and high-emissions scenarios, respectively. The darker the color, the more sea-level rise.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22774964/sea_level_rise.png) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeIf there’s one takeaway from the atlas, and the terabytes of data that went into it, it’s this: Cutting emissions will make the planet significantly more habitable in our lifetimes.

“It’s empowering to be able to examine the dramatic differences between different future carbon emissions scenarios,” Mann said, “and see that we really can make a difference through our actions.”

Author: Benji Jones

Read More