It says there is “currently no evidence” that someone cannot be reinfected.

The World Health Organization (WHO) released a scientific brief on Saturday recommending countries refrain from issuing certificates of immunity to people who have been infected with the novel coronavirus, warning there is “currently no evidence” that someone cannot be reinfected.

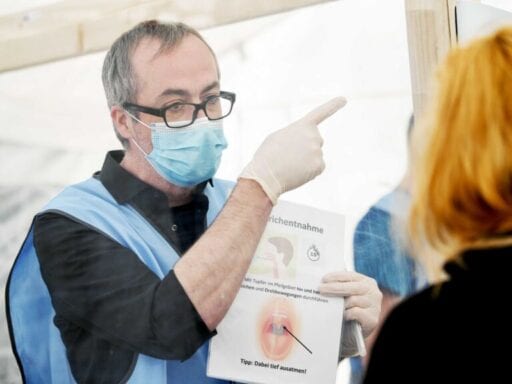

Countries like Germany and Chile are looking into giving residents “immunity passports” that would allow people who have recovered from Covid-19 to be excluded from restrictive protection measures and to work outside the house. Public health officials would use tests that detect antibodies to the virus to determine if someone has previously had the virus.

But the WHO cautioned against this practice due to concerns that reinfection cannot be ruled out based on antibodies alone.

“There is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from Covid-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection,” the WHO says in the brief.

The report went even further, suggesting immunity passports could backfire and unwittingly accelerate the spread of the virus. “People who assume that they are immune to a second infection because they have received a positive test result may ignore public health advice. The use of such certificates may therefore increase the risks of continued transmission,” the report says.

Part of the reason the WHO is counseling caution is because scientists don’t yet understand what ensures immunity to the virus.

“Most of these [antibody response] studies show that people who have recovered from infection have antibodies to the virus. However, some of these people have very low levels of neutralizing antibodies in their blood, suggesting that cellular immunity may also be critical for recovery,” the brief says.

What do we know about immunity?

The brief is a reminder that although scientists and public health experts have made great strides in their understanding of the new virus in a relatively short period of time, there’s still a lot unknown about both the coronavirus, and the disease it causes, Covid-19. One of the largest outstanding questions is whether humans can develop immunity to coronavirus and what immunity would look like.

In their deep dive into Covid-19 immunity, Vox’s Brian Resnick and Umair Irfan explain that the first issue with Covid-19 immunity is that immunity is not completely understood in general:

For reasons scientists don’t quite understand, for some infections, your immunity never wanes. People who are immune to smallpox, for example, are immune for life: Antibodies that protect against smallpox have been found as long as 88 years after a vaccination.

Less reassuring here is that scientists have observed antibody levels to other coronaviruses (there are four coronavirus strains that infect people as the common cold) can wane over a period of years. A few weeks after an infection, antibody levels will be at their highest. But “a year from now, that number is likely going to be a little bit lower, and five years from now it’s likely to be potentially a lot lower or a little bit lower, and we don’t know the factors that change that,” [University of Texas Medical Branch immunologist and coronaviruses expert Vineet] Menachery says.

However, even if you lose the antibodies, it doesn’t mean you are again completely susceptible to the virus. Yes, none of this is simple.

Part of the reason a loss of antibodies doesn’t always result in a loss of immunity is because the body stores antibody blueprints — when exposed to a virus a person already has antibodies for, the body can use those blueprints to quickly restart antibody production. Whether this would happen with antibodies effective at fighting Covid-19 isn’t known.

It is known, however, that those who have recovered from Covid-19 have a range of antibodies in their systems — some have more, others have less. The reason why isn’t yet fully understood. However, part of it, Resnick and Irfan note, may depend on when antibody tests are administered. The body tends to have the greatest number of antibodies four to eight weeks after infection, meaning someone tested in that period may have more antibodies than someone given an antibody test later on. It could also be the case, as the WHO noted in its brief, that immune responses outside of antibodies play a key role in fighting the virus.

Still, other prominent scientists note the severity of an infection may affect how many antibodies one has — as well as the strength of any possible immunity. Marc Lipsitch, a scholar of epidemiology and immunology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, wrote in the New York Times, that — based on a non-peer-reviewed study from China — he believes mild cases “might not always build up protection.”

Lipsitch said that studies of more serological surveys, or blood tests for antibodies, on large groups of people are going to be needed to make better appraisals. And they need to be sophisticated: “Much will depend on how sensitive and specific the various tests are: how well they spot SARS-CoV-2 antibodies when those are present and if they can avoid spurious signals from antibodies to related viruses,” he said.

There, however, are problems with these tests, currently; experts have expressed concern about false positives and negatives from them, and those worries have cast some new, preliminary antibody studies in serious doubt.

Beyond these concerns is a more immediate one: whether people can be reinfected. Resnick and Irfan spoke with scientists about reports from some countries that people are testing positive for coronavirus even after recovering from it — and they suggested it was an issue with testing:

The experts we spoke to say these reports are likely due to flaws in testing. “I think the risk of being infected more than once from SARS-CoV-2 is nil,” says Gregory Gray, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Duke University, in an email.

That may be because as you progress in the illness, the testing for Covid-19 becomes more inconsistent.

…

At least in the short term, it’s probably more the case that the people who have tested positive after recovering haven’t completely cleared the virus from their system or that a prior negative test was inaccurate.

Should it be the case that humans are able to become immune to the coronavirus, there is also the question of how long immunity would last.

Lipsitch says based on current evidence and what the scientific community knows about similar viruses, it’s only possible to make “an educated guess” as to immunity: “After being infected with SARS-CoV-2, most individuals will have an immune response, some better than others. That response, it may be assumed, will offer some protection over the medium term — at least a year — and then its effectiveness might decline,” he wrote.

Despite all these questions about the reliability of testing and the conditions required to achieve immunity, some countries, desperate to restart their economies, are planning on using estimates of immunity to guide policy in the immediate future. Chile is set to start issuing its “immunity passes” next week.

And earlier in April, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said it’s “possible” that the US would consider such a policy in the future.

“I mean, it’s one of those things that we talk about when we want to make sure that we know who the vulnerable people are and not,” he told CNN on April 10. “This is something that’s being discussed. I think it might actually have some merit, under certain circumstances.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Zeeshan Aleem

Read More