“By not showing up in American history, by not hearing about Asian Americans in schools, that contributes to that sense of foreignness.”

This month, Illinois became the first state in the country to require the inclusion of Asian American history in public school curriculums. While the actual impact of this law will depend a lot on implementation, its passage alone sends a significant message: that Asian American history is American history and is integral to understanding the country’s past and present.

For years, Asian American history has been virtually nonexistent in textbooks or cordoned off to a narrow section at best. Much of the framing has also sought to paint the US as a savior for Asian immigrants, glossing over people’s agency and the government’s role in imperialism and exclusion.

“My general understanding is there is not much, if any [Asian American history], being taught in most parts of the country,” says Tufts University sociology professor Natasha Warikoo, whose work centers on the study of inequality in schools. “I have not seen it in my own experience, in my children’s experience, or in my own experience as a teacher.”

This new Illinois law — the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community History Act (TEAACH) — takes a first step toward addressing some of these gaps by requiring all public elementary schools and high schools to have a unit dedicated to Asian American history. Its passage follows an increased focus on anti-Asian racism, as attacks and xenophobia have surged in the pandemic.

Grace Pai, the executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice Chicago, the advocacy group that first proposed the legislation, notes that its overwhelming passage — it was approved by the state House 108 to 10 — is a testament to the work of local organizers who’ve helped write the law and lobbied lawmakers on it over the past year. The victory comes as conservatives mount a national attack on critical race theory, or what is really education that scrutinizes systemic racism and highlights the importance of lessons that examine the country’s history of discriminatory policies.

By ensuring that more Asian American experiences are included in classroom lessons, the hope is that laws like this will build more understanding among students and combat damaging stereotypes that have persisted for decades.

“TEAACH is fundamentally at its core about building empathy,” Rep. Jennifer Gong-Gershowitz, a lead sponsor of the bill alongside state Sen. Ram Villivalam, emphasized in a press interview. “Empathy comes from understanding, and we cannot expect to do better unless we know better. And when Asian Americans are missing from our classrooms, what fills that void are harmful stereotypes.”

Asian American history has largely been missing from classrooms

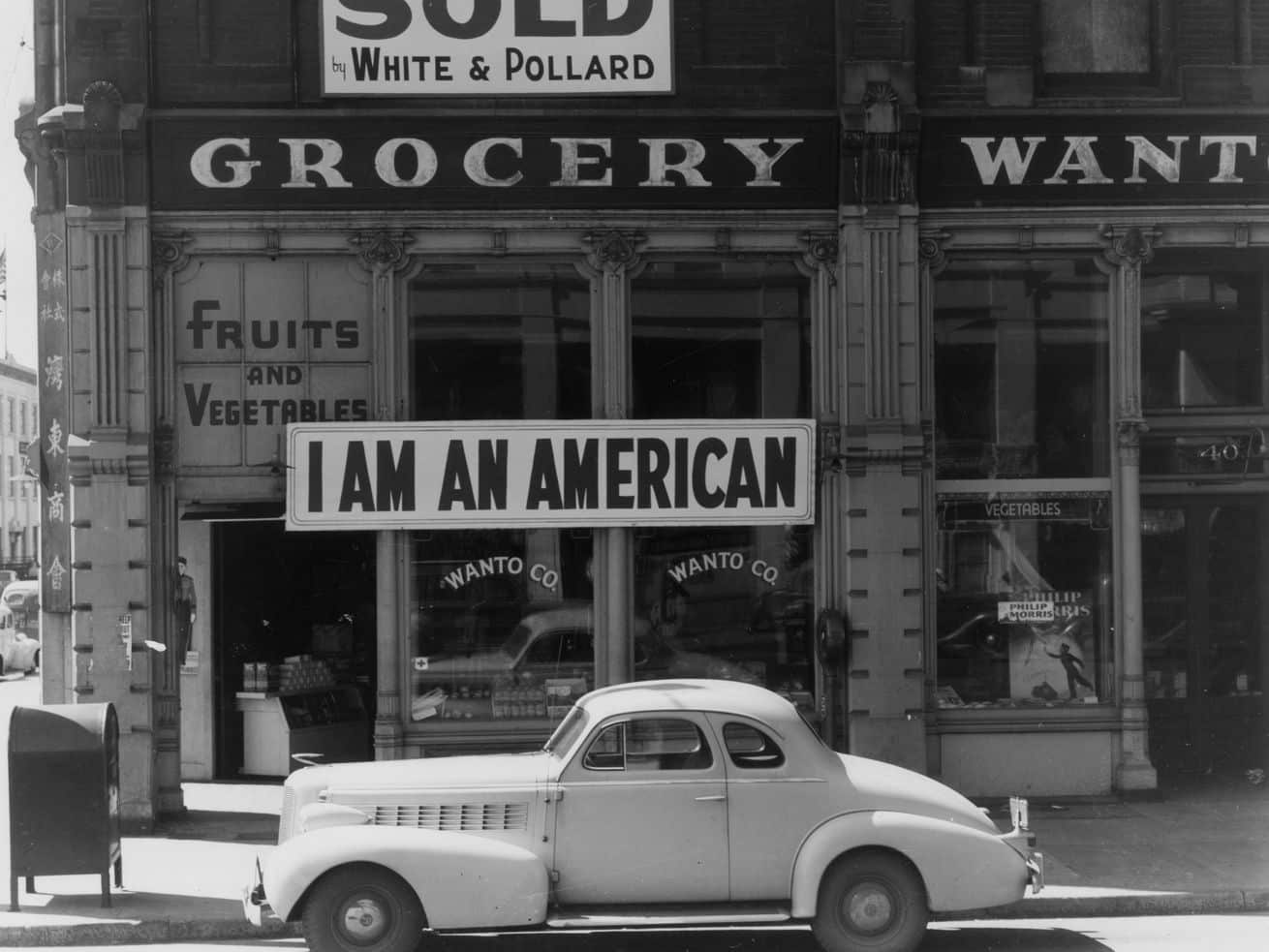

Because states and districts have jurisdiction over what’s taught in schools, curriculums about Asian American history vary widely across the country, and focus mostly on a few events, including the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred Chinese immigrants from entering the country.

In her 2016 analysis of history standards of 10 states across the country, Sohyun An, a professor of elementary and early childhood education at Kennesaw State University, discovered that most lessons centered on the treatment of Japanese and Chinese immigrants and didn’t begin to cover the immense diversity of the Asian American diaspora.

The majority of the curriculums she studied framed Asian Americans as the victims of nativist sentiment and restrictionist policies, with few highlighting them as active contributors to the country’s achievements.

“They portray them as the victims of racism, but they don’t highlight their agency,” says An.

Nicholas Hartlep, an education professor at Berea College, discovered an even starker breakdown in his 2016 review of K-12 textbooks, Pacific Standard previously reported:

His 2016 study of K-12 social studies textbooks and teacher manuals found that Asian Americans were poorly represented at best, and subjected to racist caricatures at worst. The textbooks often relied on tropes such as dragons, chopsticks, and “Oriental” font to depict Asian Americans. The wide diversity of Asian Americans was overlooked; there was very little mention of South Asians or Pacific Islanders, for example. And chances were, in the images, Asian Americans appeared in stereotypical roles, such as engineers.

And historic events are often framed in a way that paints the US government in a positive light, while obscuring its role in colonization and oppression.

“K-12 American history texts reinforce the narrative that Asian immigrants and refugees are fortunate to have been ‘helped’ and ‘saved’ by the US,” Jean Wu, a Tufts Asian American history lecturer emerita, previously told Time. “The story does not begin with US imperialist wars that were waged to take Asian wealth and resources and the resulting violence, rupture and displacement in relation to Asian lives. Few realize that there is an Asian diaspora here in the US because the US went to Asia first.”

A lot, in the end, is currently left out of textbooks. Students don’t learn about Larry Itliong, the Filipino American farmworker who led historic strikes for workers’ rights alongside Cesar Chavez; they don’t learn about Asian American activists working with other student groups to push for ethnic studies departments in the 1960s; they don’t learn about Dalip Saund, the first Asian American Congress member, who advocated for immigrant rights; and they don’t learn about activists Grace Lee Boggs or Yuri Kochiyama, both of whom fought for civil rights.

When textbooks focus on anti-Asian racism, they usually gloss over the severity of the discrimination that people endured and the resilience they exhibited in fighting back. Few history lessons address the attacks on hundreds of South Asian immigrants in Bellingham, Washington, in the early 1900s as white workers sought to drive them out, or the mass lynching of Chinese American immigrants in Los Angeles in the 1870s.

Without such lessons, there’s little awareness not only about how Asian Americans have been discriminated against in the past — and how that continues to inform current biases — but also about how Asian Americans have helped to build the country.

The omission, and limited portrayals, of Asian Americans in history lessons establishes and reinforces the message that they aren’t part of this country’s narrative.

“By not showing up in American history, by not hearing about Asian Americans in schools, that contributes to that sense of foreignness,” says Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn, a teacher educator with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Learning for Justice initiative.

The Illinois law was passed as a response to a rise in anti-Asian incidents

The Illinois bill was first proposed in early 2020 by Asian Americans Advancing Justice Chicago, and Pai notes that the recent rise in anti-Asian sentiment has underscored the urgency of the measure. Between March 2020 and March 2021, the group Stop AAPI Hate has received reports of more than 6,600 anti-Asian incidents ranging from verbal abuse to physical attacks, as lawmakers including former President Donald Trump have used racist rhetoric to describe the coronavirus. Greater history education can help students see how such statements tap into longstanding xenophobia and echo the scapegoating of Asian Americans for the spread of illnesses in the past.

While the Illinois law does not detail exactly what the curriculum should cover, it references a five-part PBS documentary about the history of Asian Americans as a useful resource. Just how much the bill will change in classrooms remains to be seen, though. School districts have a lot of leeway in how to implement the law and designate what they mean by a “unit,” so the actual lessons that are taught could have significant differences from place to place.

“The impact, in terms of children’s education, really depends on what comes next. The extent to which training is provided for teachers and school districts, the provision of curricular materials,” says Warikoo. “Even within states, there’s a lot of flexibility in state standards and how different districts and even schools and teachers implement them.”

Pai says that Asian Americans Advancing Justice Chicago is working with the state government to offer guidance for districts and teachers. “I think weak implementation is a challenge and a concern,” Pai says. “There has to be a multi-pronged strategy and that means partnering with other organizations on teacher trainings, to receive professional development around this … to provide a comprehensive set of resources,” she says.

Illinois is not the only state pursuing such changes. Others, including California and Oregon, have established ethnic studies curriculums, which include lessons on Asian American and Pacific Islander history. Connecticut also has legislation in the works to ensure that Asian American history is part of the state’s model curriculum that’s provided as an outline for schools.

“Unfortunately, it took the anti-Asian hate and violence in this country to get people’s attention, and it was a call to action,” says Karen Korematsu, the director of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute, an organization dedicated to advocating for more inclusive education.

Why teaching Asian American history matters

Expanding education to incorporate a variety of perspectives is viewed as a key way to build empathy and critical thinking among students, which could, in turn, reduce bias. While it’s certainly far from the only thing that’s needed, this curriculum is viewed as one way to help prevent anti-Asian attacks moving forward.

“If you’re thoughtfully inclusive, really helping kids see that difference is not something to be scared of or a bad thing, that can really support empathy. And in a moment when we are seeing more awareness in anti-Asian hate and violence sometimes, that is probably a good thing,” says Blackburn.

Research on children’s literature indicates that exposure to diverse voices can change students’ perceptions: A 2012 Michigan Reading Journal paper from educators Rose Crowley, Monica Fountain, and Rachelle Torres found that consuming children’s literature with diverse protagonists helped children develop more understanding of people who were of different backgrounds. Previous studies have also found that such books can help push back on stereotypes children may hold.

Such lessons also ensure that Asian American students feel seen and included.

“It’s hard for children. … When you don’t know about the contributions of Asian Americans and you’re an Asian American yourself, you don’t have mentors and people to look up to,” says Hartlep. “If you don’t see yourself in the curriculum, and you don’t see yourself in the classroom, it’s like, where do you belong? It makes you feel invisible and it doesn’t lead to empowerment.”

This bill points to the important role that schools can play in providing important historic context that informs students and nurtures empathy. It’s also just the latest act the state has taken to make its public school curriculums more inclusive: Last year, Illinois approved a new law requiring history lessons to include the contributions of LGBTQ people, and earlier this spring, another law expanded the scope of Black history taught in schools.

Pai notes that the GOP focus on critical race theory — a term that’s been used as a catchall by conservatives to describe education that addresses race — did not play a major role in the discussions of this bill, which garnered widespread support in Illinois’s mostly Democratic legislature.

Experts have also theorized that this legislation’s focus on the inclusion of Asian American history and contributions, rather than calling out systemic racism outright, may have made it less likely to prompt conservative pushback. “This law … doesn’t call out white supremacy, so it can be very palatable,” says Hartlep.

An, the Kennesaw State curriculums expert, says that Illinois’s actions could spur momentum for concurrent efforts taking place in other states, though she says comparable bills are likely to be a tougher sell in more conservative places, like Georgia, where she lives. Still, it’s a change that helps set a precedent, she says.

“We have a grassroots movement right now to benchmark Illinois and do something similar,” An says.

Author: Li Zhou

Read More