An expert explains why the US struggles with modern wars.

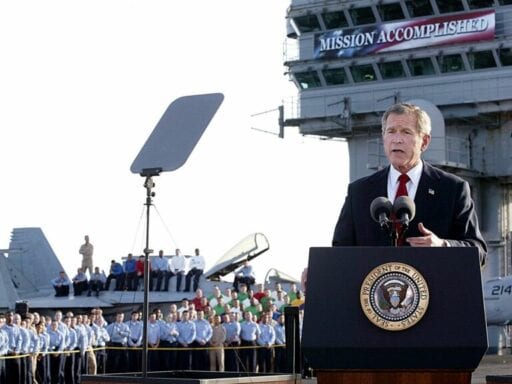

A month into his presidency, Donald Trump lamented that the US no longer wins wars as it once did.

“When I was young, in high school and college, everybody used to say we never lost a war,” Trump told a group of US governors last February. “Now, we never win a war.”

Dominic Tierney, a professor at Swarthmore College and the author of multiple books about how America wages war, may know the reason why.

He believes the US can still successfully fight the wars of yesteryear — World War-style conflicts — but hasn’t yet mastered how to win wars against insurgents, which are smaller fights against groups within countries. The problem is the US continues to involve itself in those kinds of fights.

“We’re still stuck in this view that war is like the Super Bowl: We meet on the field, both sides have uniforms, we score points, someone wins, and when the game ends you go home,” he told me. “That’s not what war is like now.”

The US military is currently mired in conflicts in countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. It’s hard to see any end in sight — especially an end where the United States is the victor, however that’s defined.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Alex Ward

During his first year in office, Trump got the US more deeply involved in wars, with the goal of defeating terrorists in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and Somalia. But has this put the US on course to end these fights?

Dominic Tierney

Victory may be asking a lot.

Since 1945, the United States has very rarely achieved meaningful victory. The United States has fought five major wars — Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, Iraq, Afghanistan — and only the Gulf War in 1991 can really be classified as a clear success.

There are reasons for that, primarily the shift in the nature of war to civil conflicts, where the United States has struggled. Trump himself recognized this: He said on the campaign trail numerous times that we used to win wars and we don’t win anymore. And he has promised to turn the page on this era of defeat and said that we were going to get sick and tired of winning.

But will he channel that observation into winning wars? I doubt it.

The nature of war continues to be these difficult internal conflicts in places like Afghanistan, where the United States has struggled long before Trump ever dreamed of running for president.

Alex Ward

So what constitutes victory in war today, and has that changed from the past?

Dominic Tierney

The famous war theorist Carl von Clausewitz argued that war is the continuation of politics by other means. So war is not just about blowing things up — it’s about achieving political goals.

The United States, up until 1945, won virtually all the major wars that it fought. The reason is those wars were overwhelmingly wars between countries. The US has always been very good at that.

But that kind of war has become the exception. If you look around the world today, about 90 percent of wars are civil wars. These are complex insurgencies, sometimes involving different rebel groups, where the government faces a crisis of legitimacy.

The US has found, for various reasons, that it’s far more difficult to achieve its goals in these cases. The three longest wars in US history are Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan — all from recent decades, all these complex types of civil wars.

Alex Ward

On its face, this seems to be a paradox: The US can win on the battlefield against a major military force, but we can’t seem to win these smaller wars.

Dominic Tierney

Yes. And even more surprising: It’s when the US became a superpower and created the best-trained, strongest military the world has ever seen, around 1945, that the US stopped winning wars.

The answer to the puzzle is that American power turned out to be a double-edged sword.

The US was so powerful after World War II, especially after the Soviet Union disappeared, that Washington was tempted to intervene in distant conflicts around the world in places like Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

We ended up intervening in countries where we had little cultural understanding. To illustrate this, in 2006 — at the height of the Iraq War — there were 1,000 officials in the US embassy in Baghdad, but only six of them spoke Arabic.

In addition, the US military has failed to adapt to this new era of war. The US military has this playbook for success against countries: technology, big-unit warfare, and so on. And when we started fighting insurgents, it was natural that we would turn to that same playbook.

Alex Ward

So we might not have much cultural understanding of the places where we’re fighting, but we have greater technology and better fighting forces. Why can’t we overcome this obstacle?

Dominic Tierney

The reason, again, comes down to the difference between an interstate [more traditional] war and a counterinsurgency, or nation-building mission.

One difference is that we cannot easily see the enemy. In an interstate war, the enemy is wearing uniforms, we know where they are on a map. In a counterinsurgency they are hiding in the population.

Now, the US military is capable of hitting any target with pinpoint accuracy using the latest hardware. But what if we don’t know where the enemy is? A lot of that technology, which is really impressive, turns out to be irrelevant.

Alex Ward

It seems like we have two problems here. We haven’t corrected our way of thinking to deal with insurgencies or civil wars, and then we keep getting involved in those kinds of wars, despite the fact that we’re ill-prepared to deal with them.

Why do we keep falling into this trap?

Dominic Tierney

One answer is we basically believe in illusions — the idea that nation-building and counterinsurgency will be avoided.

Look at Iraq, where the United States believed it could topple Saddam Hussein and basically leave as quickly as possible. We would overthrow the tyrant and then the Iraqi people would be free to create their own democracy. That was based on massive overconfidence about what would happen after Hussein fell.

So why do we go to war if we hate counterinsurgency and we struggle at it? The reason is the White House convinces itself it doesn’t need to stabilize or help rebuild a country after a war. But it’s not just the Bush administration — think of the Obama administration too.

Barack Obama was a very thoughtful president and talked at length about his foreign policy thinking. At the heart of the Obama doctrine was “no more Iraq War.” And yet he basically made the same mistake in Libya, where there was very little planning for what would occur after Muammar Qaddafi was overthrown in 2011. In fact, Obama went on the record saying that the Libya intervention was his worst mistake a president.

Alex Ward

So if it really is a bunch of wishful illusions and incorrect assumptions, how do we avoid that? We have tons of evidence that things don’t go our way when we get involved in these kinds of wars. We don’t seem to learn from our mistakes.

Dominic Tierney

We don’t learn very well from history. Presidents convince themselves that the next time will be different.

The lesson Obama took from Iraq was not to allow any US ground forces to get involved in nation-building. Since Obama was willing to support regime change, the end result was going to be the overthrow of Qaddafi with no real plan to stabilize Libya.

If a thoughtful president like Obama — who was very cognizant of the errors of Iraq — can do that, it suggests that any president would be capable of doing that.

Alex Ward

It seems like one of the problems is that we’re involving ourselves in these wars with little preparation. How do we solve that?

Dominic Tierney

We need better language training, cultural training, more resources for special forces — and that would mean less money spent on nuclear attack submarines, for example.

Second, once we improve America’s ability for stabilization missions, we deploy the US military with greater care and fight fewer wars. That means when we do fight, we have a better plan to win the peace.

Alex Ward

But then there’s another problem: Sometimes groups like ISIS arise, and US leaders and many Americans want the military to take them out. So when the president is faced with the option to target a group like ISIS with airpower, some would argue that it’s better, politically, to do that.

Dominic Tierney

The US doesn’t think several moves ahead. The US military is good at taking out bad guys. But the removal of the bad guy creates a power vacuum, and that power vacuum is filled by somebody else.

In Afghanistan, we created disorder and then the Taliban returned — the power vacuum there was also filled by ISIS. And in Iraq, the vacuum was filled by militant groups, most notably al-Qaeda in Iraq. In Libya, the vacuum was filled by a complicated range of militant groups.

The mood in the US is: “We just killed ISIS, let’s go home and close the book on the ISIS war.” Well, there’s more to the story.

Alex Ward

The Trump administration says it will pay less attention to defeating terrorists and will now focus more on battling back growing Chinese and Russian power.

That new strategic focus means we’ll change the kinds of weapons we buy and the kind of training our troops do. But I don’t see the US stopping its fight against terrorism. Does this preparation for a different style of war — while still fighting another — put the US in an awkward position?

Dominic Tierney

I think it does.

There is a desire to shift from difficult nation-building missions toward countering great-power challengers like Russia and especially China. But this isn’t very new. The Obama administration wanted to pivot to Asia and the China challenge. And then what happened? We ended up being engaged against ISIS.

I tend to think that the pivot to China is sort of like Waiting for Godot — it never arrives. And I think the United States is going to get drawn back into these civil wars and these kinds of messy conflicts, particularly in the broader Middle East. The odds of conflict between the US and China are very low; the odds of the US engaging in another civil war in the next five years are extremely high.

Alex Ward

Based on this conversation, victory in war seems to be how we define it, or, rather, will it to be. The US sets its victory goals low, but we don’t even meet those lower goals. Why can’t we get over this hump?

Dominic Tierney

We’re still stuck in this view that war is like the Super Bowl: We meet on the field, both sides have uniforms, we score points, someone wins, and when the game ends you go home. That’s not what war is like now. Now there are tons of civilians on the field, the enemy team doesn’t wear a uniform, and the game never ends. We need to know there’s no neat ending.

The costs of this problem have been so catastrophic for the United States, in the form of thousands of military lives and billions of dollars spent. It’s time we fundamentally rethink our vision of what war is.

Author: Alex Ward