A conversation with author Kiese Laymon on writing, revision, and the unfinished — and contested — story of America.

Is a work ever complete, or is it merely abandoned?

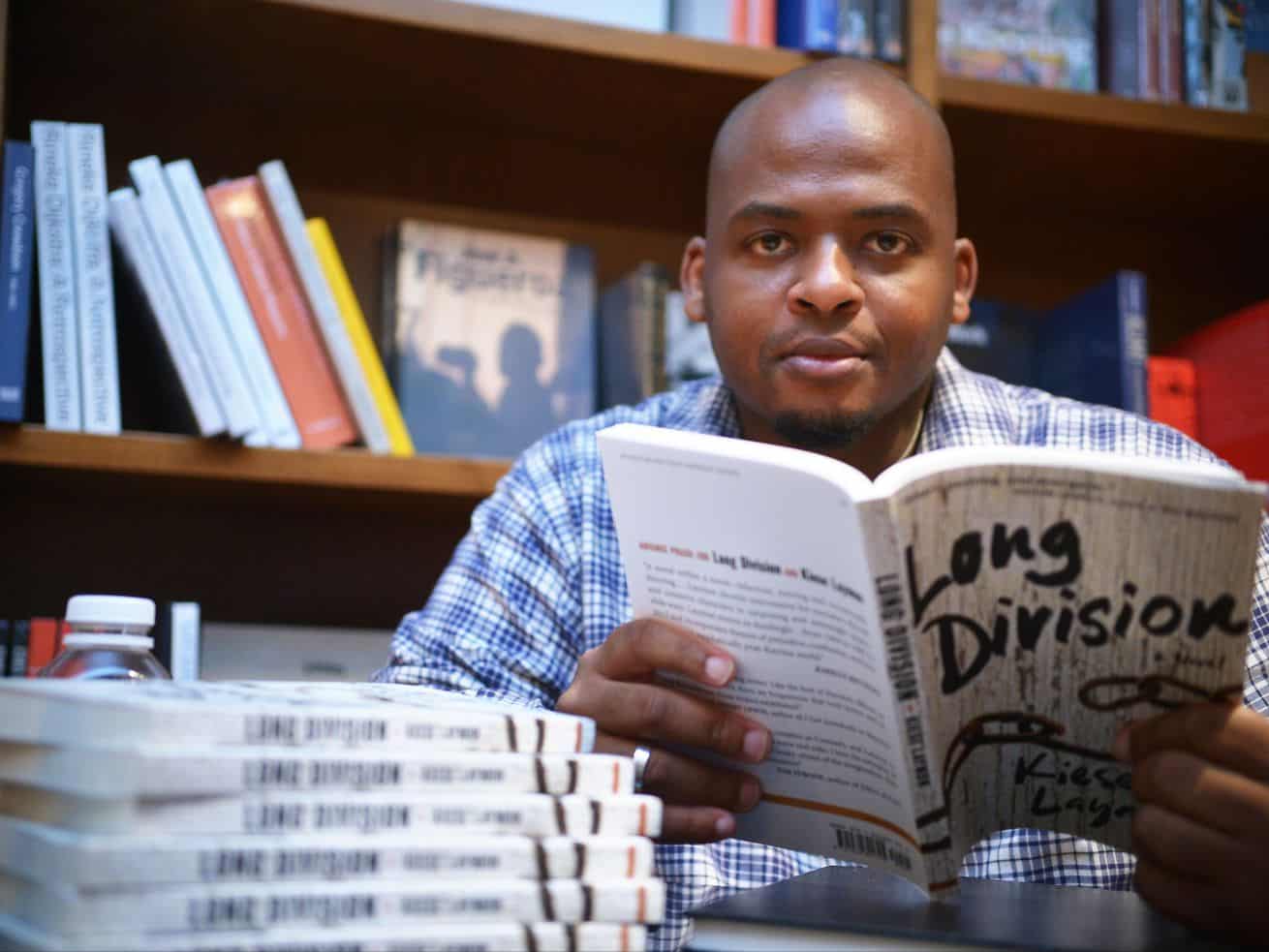

In the years since publishing his bestselling memoir Heavy, author Kiese Laymon has won multiple accolades and awards, among them the 2019 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. But rather than moving forward into a new work, Laymon has turned back, revisiting the two books that first introduced him to many readers, including myself.

For about 10 times the amount he was paid to write them, Laymon re-acquired, revised, and republished his debut novel, Long Division, as well as the essay collection How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. No one was forcing him to revise the works, which were roundly praised at the time. But having seen his original vision for Long Division rejected by New York agents and publishers, he felt compelled to put before readers the novel “as I imagined it.”

The June republication of those two works prodded me to ask Laymon, a Mississippi native who now teaches at Ole Miss, about the concept of revision — in the narrow, literal sense and on a more metaphorical register. We spoke in the midst of Republican efforts to ban the teaching of critical race theory, an academic term currently serving as a placeholder for the party’s broader war on critical thinking about America and its past.

In a May essay for Vox’s The Highlight, Laymon wrote that the “metastasized, excused unwellness in white families, monied and poor, is responsible for anti-Black terror happening in this nation’s schools, prisons, hospitals, neighborhoods, and banks.” This, he offered, “is the work of folks who despise revision nearly as much as they despise themselves.”

You can hear our entire conversation (and there’s much more to it) in this week’s episode of Vox Conversations. A partial transcript, edited for length and clarity, follows. (Some of what you read below may not appear in the published podcast episode.)

Subscribe to Vox Conversations on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Jamil Smith

I wanted to start by talking about words and revision. I think a lot about language; you think a lot about language. How were you first taught to use your words?

Kiese Laymon

It was the sound, right? I was taught to use my words to get people’s attention.

I think you can use words to make yourself invisible. I was the only kid in my family, so sometimes they would be like, “Hey, you gotta be quiet.” But I learned early, you could use words so it appeared that you were quiet, even if you weren’t. My first foray into words was just listening, and trying to decide how present I wanted to be and how invisible I wanted to be.

My mother, she had me when she was really young. She was at Jackson State [University, in Mississippi] when she had me. She came back to teach at Jackson State five years after she had me. And she was obsessed with written words.

Jamil Smith

What happened with your two revised and recently rereleased works, Long Division and How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, and why did you end up paying 10 times what they paid for the rights to your books?

Kiese Laymon

Oh, so happy I can laugh at that now. That’s so interesting, you asking me that and my body’s reaction was to laugh.

The short version is I signed a terrible deal. And I had to sign a terrible deal because none of the publishers in New York really wanted me — and the one that did want me told me to change the narrator (of Long Division) from a Black person to a white person, change the place, change the setting. But when they told me to take the racial politics out, I gave them their little money back.

My friend Jesmyn Ward had just published this book, Where the Line Bleeds, with this press out of Illinois. I just sent them, like, three books one Thursday. And they hit me back, being like, “We wanna publish, but we wanna make these two novels into one and we wanna sell the essay collection as sort of an aside.” And they offered me $1,000 for the essay collection, and they offered me I think $2,000 or $3,000 for Long Division.

Then those books went on to sell, like, 60,000 copies. I also signed away my TV rights, signed away my movie rights — I signed away every right possible. A few years later, when I went back to try to revise the books, the publisher was like, “No, we can’t do that.” And I said, “Okay, well, I want my books back.”

I sold my books for $4,000, both of them. I then paid $50,000 to get them back to publish them the way I wanted to.

Jamil Smith

Especially as Black writers, man, we are in the business of opening up ourselves, not just to the reading public but also to the pain that we’ve already experienced. I can only imagine your pain, all disassembled in this experience. You had to revisit that.

What, then, is revising? In that Highlight essay, you called it the “rugged majesty of revision.” What did you mean by that?

Kiese Laymon

I think I was lucky in that Long Division is essentially about the need for all of us to revise. The unfair burden we put on young Black children to revise adult mistakes. So revision was already something I was taken by and working with.

And then the last essay in the first version of How to Slowly had me write a letter to my mom, and I tell her we owe it to each other to commit to revising, and talking to each other about what we revise. So those two texts were already steeped in revision.

And then it was, can I walk the walk? Anybody who publishes a book, five or six years later, you’re gonna look back and be like, “Damn, that could have been better.” And I think a lot of us, we just try to not make the same mistakes or build on something we did poorly in our next creation. And I did that with Heavy — but at the same time, there were just some essays that I was very messy and sloppy with, and I wanted to take those out. I just couldn’t stand by them anymore ethically. You know what I’m saying? Not to erase them, but to work on them further and put them out in a different way.

And so, now that I’m thinking through it, I think it was like a way of loving the process, and that process almost killed me. I just needed to revisit that, and revisit the work that I was doing during the process of trying to keep myself alive.

You just start to feel every time you get told “no” as a writer, if you put your entire identity into writing, you’re being told that you ain’t worth shit, right? And that’s my fault for hearing it that way, but I just wanted to love myself enough to go back and change the art I created during that time.

Jamil Smith

Some of the essays that you felt like you couldn’t stand by anymore … can you be more specific?

Kiese Laymon

I’d written this one essay about Kanye and Black men who purported to be feminists. It was also about labor. I was trying to say that Kanye, at the time I wrote it, was doing incredible things with, like, song structure. Not just what he said, but how he made songs.

But if you look, not even that deeply, you can see Kanye’s brutal blind spot was gender. And I was trying to do that thing where I want to knock him as a Black feminist. But at the same time, I needed to put the oh-so-perceptive flashlight onto myself and talk about my complicity. I couldn’t stand behind what I said about Kanye. And I couldn’t stand behind some of what I said about myself, as a cisgender Black man who purports to be a feminist.

Jamil Smith

In what way?

Kiese Laymon

It’s so easy to dis Kanye because … look, I’m a Black feminist. And I did that, but I was trying to critique that. But even in critiquing that, I still was using shorthand. I still was basking in the aura of being a man who knew what misogyny was, who knew what misogynoir was. The essay’s a lot more “Look at me, I’m special,” when that was not at all what it was supposed to be. I realized that I was using Kanye sort of to not deal with my relationship with the man who married my grandmother. And some of it was aesthetic and some of it was ethical, do you know what I mean? I just didn’t write the essay well.

Jamil Smith

Us being Black men, us being self-identified feminists. It’s something that you not only have to earn, but you also have to maintain it.

Kiese Laymon

Absolutely, absolutely. And I think it’s easy to accept the work of maintenance. Once I understood that everyone who calls themselves feminists has to do the work of making sure that our actions and our supported theory align, it just became easier for me to walk away from these battles where I’m up there like, “It is I, the Black feminist man.” You know? Like, shut up, bro. It is not you, bro.

Jamil Smith

“Speaking from the mountaintop of Black feminism.”

Kiese Laymon

… nobody cares. [Laughs] But part of that is because you get patted on the back so much — it’s like we do [with] white people, you know what I mean?

Jamil Smith

I feel this all the time, bro. They post the black squares or they get the verbiage down. And I’m thinking, “Okay, they’ve just taken the remedial course.” We, as Black people, are forced to master whiteness; we’re forced to be fluent in it. From the jump. We know how it’s perceived; we know how they operate — because we have to learn it in order to navigate and survive. They don’t have to learn about Blackness in the same way.

And so, when all of this is thrust upon them, whenever one of us is killed by a police officer or one of us may be elected president, there’s always this kind of reckoning that’s done for, you know, a week, couple weeks, couple months. Last year we had the longest one I’ve seen. But we haven’t gotten to the truth and reconciliation.

One of the things that all this talk about revision makes me consider is, Republicans seem to understand this almost better than Democrats do. They’re the ones who are out here talking about critical race theory, and using that as the boogeyman to criminalize Blackness and to criminalize anti-racism. They understand the threat of anti-racism. And they want to get after this threat. And meanwhile, we’re sitting here trying to say, “Well, no, let us explain critical race theory to you.”

Kiese Laymon

[Laughs] Right.

Jamil Smith

“Let me break down the tenets.”

Kiese Laymon

Right.

Jamil Smith

I mean, if you can do that, that’s cool. I had a blessed household where my mother put Derrick Bell on my shelf when I was a child. So, you can go read Derrick Bell, go read Kimberlé Crenshaw. There’s a whole reader for this stuff. Be curious. But that’s not what this is about. If we’re talking about wanting to actually do the repair, to talk about fairness — it has to be on an individual level as well as a national level.

Kiese Laymon

It does. And we have to not just ask hard questions but be willing to give hard, wrong answers. And the ill shit is not that white folks don’t know us, right? It’s that they don’t know themselves, and then they ask us for help.

But I don’t think we can even get there unless we think about the fact that often we, as cisgender men … well, we’re not asking enough. But often, we’re asking women and femmes to tell us about ourselves. And white people are doing the same thing. My granny was trying to talk to white people whose houses she cleaned. In the nicest, most Christian way possible. And they gave her fucking $2.50, you know? This is where I think the reparation and the repair come in.

Essential workers day-to-day are being asked in so many ways, verbal and nonverbal, to teach the elites about themselves. But, like, what’s the payout? We did all that work, and then we come out of it and now you all are talking about critical race theory? Some shit that probably, like, 1,500 people in the country actually understand. It’s just ridiculous, bro.

Jamil Smith

And they want us to think that racism is a thing of the past. I think the real reason behind all this is that racism has been commonly accepted as villainous. They understand how villainous this is. That’s why folks get so excited about “You’re calling me a racist,” and we talk more about that than the actual racism.

Kiese Laymon

It’s like you said: It’s a criminalization of critiques of whiteness. That’s a very generous way for me to put it, right? And I see this criminalization of critiques of white supremacy. These are the same people who made Barack Obama into a racial warrior who was coming for them. A man who would do everything in his power to make them feel like he was not critiquing their whiteness. And I’m just saying this isn’t a diss of Obama, as much as it is. We knew where these folks were going.

Jamil Smith

This essay that you wrote six years ago, in the aftermath of a white terrorist murdering nine black people during a Bible study in South Carolina. You wrote for the Guardian about Black folks and forgiveness and what we are taught, and how that teaching of forgiveness metastasizes into something that’s actually malignant. The shame that we carry with us.

I want to go back to that right now, because what we’re seeing is folks trying to make people forget the past. I think I see something that’s connected between what we were encouraged to do then, which is pray for our enemies and all that, and right now, when folks are literally passing laws that prevent teachers from teaching about our own history.

Kiese Laymon

And passing laws which prevent them from learning about their own history. An accurate assessment of that has to start with the way these people see themselves. Like, besides how mad I get about what they did to my grandma, what they do to you, what they do to me, what they do to the most vulnerable people in this culture, I’m just like, “Yo, how could y’all do that to your own children? How could you do that to yourself?”

So when you have lawmakers out there, not just saying, “We’re not gonna teach this black history,” but “We’re not going to tell white kids the truth about where they come from,” … you have a nation that at its best can do nothing but hold on for dear life, fam. Because that is the core of that desire to not teach your children, to not encourage your children to revise, to go circular. You teach people not to go back and look honestly, and assess how they got here. And that is the pitiful part of it all.

Author: Jamil Smith

Read More