The Sanders campaign and his supporters bet on a theory of class politics that turned out to be wrong.

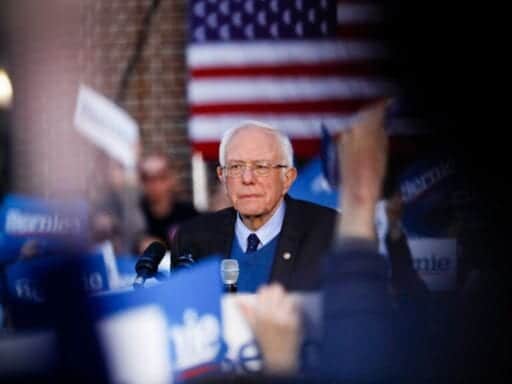

Sen. Bernie Sanders’s theory of victory was simple: An unapologetically socialist politics centering Medicare-for-all and welfare state expansions would unite the working class and turn out young people at unprecedented rates, creating a multiracial, multigenerational coalition that could lead Sanders to the Democratic nomination and the White House.

“When we bring millions of working people, people of color and young people in the political process, there is nothing we cannot accomplish,” Sanders wrote in a February 2 Facebook post.

This theory of class politics informed the Sanders strategy from the very beginning of the campaign. The campaign targeted its outreach at low-income and habitual non-voters, with the explicit aim of building a new, working-class electorate — an approach supported by many of his backers in the media and the academy. In a 2019 essay in the socialist magazine Jacobin, Princeton professor Matt Karp staked his case for Sanders on the candidate’s ability to win over economically precarious voters by appealing to their common interest.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19888810/GettyImages_1206512109.jpg) Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty Images“Sanders in 2016 won more than 13 million votes from a much younger, less affluent, and less educated swath of the electorate,” Karp writes. “The core of Bernie’s support comes from voters with a far more urgent material interest in the social-democratic programs he proposes, and a far clearer position in the class struggle that he has helped bring to the fore.”

In the end, this approach failed. It was former Vice President Joe Biden, not Bernie Sanders, who assembled a multiracial working-class coalition in key states like Michigan — where the former vice president won every single county, regardless of income levels or racial demographics. Sanders had strong support among younger voters, but they did not turn out in overwhelming numbers. In at least some key states, they made up a smaller portion of the primary electorate than in 2016.

Sanders’s defeat is a hammer blow to the left’s class-based theory of winning political power, especially given socialist Jeremy Corbyn’s crushing losses among the working class in the 2019 UK election.

Sanders had success in shifting the Democratic Party in his direction on policy. But the strategy for winning power embraced by his partisans depended on a mythologized and out-of-date theory of blue-collar political behavior, one that assumes that a portion of the electorate crying out for socialism on the basis of their class interest. Identity, in all its complexities, appears to be far more powerful in shaping voters’ behaviors than the material interests given pride of place in Marxist theory.

Class conflict doesn’t dominate the American political scene, and Sanders’s campaign couldn’t make it so. Under these conditions, the Sanders campaign looked to the wrong segment of the electorate for salvation.

“The future of [Bernie’s] agenda lies with young people, but college-educated and suburban voters are increasingly interested in the progressive agenda,” Sean McElwee, co-founder of the left-wing polling outfit Data for Progress, tells me. “Sadly, we [progressives] are about four years behind in reaching out to those voters because people don’t read enough fucking polling data.”

If leftists want to make the leap from influencing the Democratic Party to running it, they need a new theory of victory.

How Sanders’s theory failed

The 2016 primary election made the left’s theory of the case seem decently plausible. Clinton won by dominating among black voters, older voters, and highly educated white professionals. Sanders, by contrast, performed well among rural and working-class whites (who voted for Clinton over Obama in 2008) and young voters of all races.

Sanders’s challenge in 2020 was to hold this ground, build his support among non-white blue-collar voters, and increase youth turnout. For the first three states, it looked it might work, especially since his campaign had proved wildly successful with early state Latino communities.

Then came Joe Biden’s overwhelming victory in South Carolina, which showed that Sanders’ coalition was still weak among one vital constituency: black voters. Shortly after South Carolina was Super Tuesday, where Biden won 10 out of the 15 contests — and snatched away the white working-class and rural supporters that were so vital for Sanders in 2016.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19888816/GettyImages_1210244075.jpg) Mario Tama/Getty Images

Mario Tama/Getty ImagesIn Minnesota and Oklahoma, two Super Tuesday states with large rural white populations, Sanders went from winning nearly all of the counties to losing (nearly) all of them. FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley found that, by April 1, Biden had won nearly 83 percent of counties that Sanders had won at that point in 2016. A significant chunk of this reversal, he finds, came as a result of non-college and rural whites flipping from Sanders in 2016 to Biden in 2020.

“In the 10 states that voted in March for which we have both 2016 and 2020 exit poll data, Sanders edged out Clinton among white voters without a college degree in 2016, 54 percent to 44 percent,” Skelley wrote. “In 2020, Biden beat Sanders, 40 percent to 33 percent in those same states.”

It’s hard to overstate how central the theory of Sanders’s popularity with middle- and lower-income whites was to his campaign and its outside supporters. They saw his unique touch with his voters as not just a strategy for winning the campaign, but a key reason why socialism as a political project was viable in today’s America.

“As in 2016, Bernie is different from other Democrats in that he knows how to speak to Trump’s own voters. Not only does he beat Trump consistently in head-to-head polling, but he offers ordinary people an ambitious social democratic agenda that is designed to deal with their real-world problems,” Nathan J. Robinson wrote in March in the leftist magazine Current Affairs. “When Bernie tells working people he is in their corner, they can believe him.”

The failure of this approach meant that Sanders needed to rely heavily on the second prong of his 2016 coalition, young voters, turning out in large numbers. This too is consistent with the socialist theory of victory, which would expect young people who have faced precarious employment and a lower standard of living than their parents would find left politics appealing.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19888832/GettyImages_1211201704.jpg) Scott Olson/Getty Images

Scott Olson/Getty Images“The source of Sanders’s youth appeal appears to be much the same as it was in 2016: Student-loan debt and escalating health-care costs are still significant burdens for young people, and incremental solutions … seem unequal to the radical challenges they face,” Sarah Jones wrote in New York magazine in January. “With so many candidates competing for votes, a committed, cohesive bloc of young adults could make a real difference for him in his quest for the nomination.”

It’s true that young voters from all races and classes tilt heavily in Sanders’s direction. The problem is that his campaign couldn’t get them to act on their beliefs.

John Hudak, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank, took a close look at exit poll data on the share of the electorate made up by voters aged 17-29 in 12 early primary states. He found that in all but one of them — Iowa — these young voters made up a smaller share of the primary electorate than they did in 2016. The numbers decreased by a quarter in Texas (down from 20 percent of eligible voters to 15) and about a third in Tennessee (from 15 percent down to 11).

“Even a stagnant percentage between 2016 and 2020 would present a challenge for Mr. Sanders,” Hudak writes. “A decrease poses a serious challenge to the very premise of his campaign.”

Why Sanders’s theory failed

So what happened? Why didn’t the political revolution show up?

This is the sort of thing that political scientists and Democratic activists are going to be examining for years. But there are at least three big conclusions that we can draw that seem relatively well-supported by polling and research.

The first is that the Sanders theory rested in part on a Marx-inflected theory of how people think about politics. A basic premise of Marxist political strategy is that people should behave according to their material self-interest as assessed by Marxists — which is to say, their class interests. Proposing policies like Medicare-for-all, which would plausibly alleviate the suffering of the working class, should be effective at galvanizing working-class voters to turn out for left parties.

But this isn’t really how politics works, at least in the contemporary United States. Political scientists have found that, as a general rule, the specifics of policy positions and campaign rhetoric play little role in mobilizing turnout for a campaign.

No matter how many times Sanders repeated his passionate defense of universal health care, no matter how often his volunteers went door to door arguing for social democratic policies, the content of the policy messages wasn’t going to convince young people and economically disaffected non-voters to show up in the way he needed.

“Most of the field experiments that I’ve seen — the published work in political science, as well as the internal tests within the progressive community — show that talking about policies and issues does not really spur turnout,” says John Sides, a political scientist at Vanderbilt University.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19888836/GettyImages_1206118835.jpg) Brittany Greeson/Getty Images

Brittany Greeson/Getty ImagesSecond, it seems that Sanders and his campaign assumed that his popularity with the white working class in 2016 was about him and his policies — when, in fact, it wasn’t.

“The white working-class voters that Sanders won were mostly anti-Clinton voters,” McElwee tells me.

A regression analysis by FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver finds support for this theory. Silver’s data shows that Clinton-skeptical Bernie supporters in 2016 were not progressives who opposed Clinton from the left, but from moderate or conservative Democrats who tended to have right-leaning views on racial issues and were more likely to support repealing Obamacare. These #NeverHillary voters also tended to be rural, lower-class, and white.

For some of these voters, Sanders may have been a protest vote against a woman closely identified with progressive social causes. When the alternative was Joe Biden, a male Democrat with working-class appeal who’s widely perceived as a moderate, they seemed to have preferred him over the Vermont socialist.

Third, the Sanders-socialist theory rested on a misunderstanding of the way identity works in contemporary American politics.

Americans do not primarily vote as a member of an economic class, but rather as a member of a party and identity group (race, religion, etc). Trump won the overwhelming bulk of Republican voters in the 2016 general election, despite taking heterodox positions on a number of policy issues, simply because he had an R next to his name. His message resonated with working-class whites, but not working-class people of color, because it centered ethnic grievance and conflict.

This created a big problem for Sanders. His refusal to formally become a Democrat — and harsh attacks on the “Democratic establishment” — were much less likely to resonate with voters strongly attached to the Democratic Party. This effect seems to have hurt him badly.

“The Super Tuesday exit polls showed Biden beating Sanders among self-identified Democrats by about 30 percentage points in both Virginia and North Carolina, about 25 points in Oklahoma, 20 points in Tennessee, and nearly 50 in Alabama,” the Atlantic’s Ron Brownstein reports.

Partisanship seems to be particularly important in Sanders’s inability to make inroads among black Democrats, especially older ones. In their new book Steadfast Democrats, political scientists Chryl Laird and Ismail White find that black political identity in the United States centers on affiliation with the Democratic party, which is understood among African-Americans as a vital part of being committed to racial progress and in-group solidarity. While a significant share of black voters have conservative views on policy issues, overall they are overwhelmingly committed to the Democratic Party as an institution.

You can’t have a multiracial working-class coalition that wins a Democratic primary without significant support among black Americans. Sanders’s team recognized this and worked hard to court black voters.

But it seems that Sanders’s insurgent identity, his explicit decision to run as an outsider in order to appeal to habitual non-voters, may well have doomed him with this vital constituency.

There is no demographic miracle for the left

There used to be a time when this kind of class politics was quite powerful — both in the United States and, especially, in Europe. For much of the 20th century, one’s class was a powerful predictor of who won was likely to vote for across the Western world.

Yet this has changed. In recent decades, the Alford Index — a metric political scientists use to measure the role of class in voting patterns — has been in decline across Western democracies. The working class is no longer overwhelmingly likely to support left-wing parties, the upper classes no longer joined by their support for right-leaning ones.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19888838/GettyImages_1206134385.jpg) Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesInstead, class division has been replaced by education divides. Highly educated high income voters have tended to defect to center-left parties — think doctors — while non-college low-income voters have defected to the right. This reflects the fact that debates over social issues like immigration and gender roles, rather than issues of material redistribution, are the primary cleavages dividing Western publics. Attitudes surrounding tolerance and diversity, not redistribution, are the clearest predictor of which kind of party you’re interested in supporting nowadays.

The dominant theory among Sanders and his left-wing supporters is that Democrats and other center-left parties, like Britain’s Labour party, allowed this to happen by embracing more market-friendly politics under leaders like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. Sanders’s rejection of this so-called “neoliberal” approach should have been able to reverse the trend — bring back the working-class voters Democrats had previously left behind.

“Sanders … points to an alternate future for class politics itself,” writes Karp, the Princeton professor. He continues:

His support of Medicare for All is not a pledge to find the best policy “framework,” but a vow to fight the private insurance industry until every American has health care as a human right. This is the kind of class politics that has won Sanders the support of 1 million small donors, faster than any candidate in history…

This is just what is required to challenge the power of the ultrarich: a politics that does not treat lower-income voters as a kind of passive supplement for professional liberals, but one that can put the new working class itself at the center of the action.

I’m not going to try to adjudicate whether the underlying theory, that neoliberalism caused the decline in class voting, is correct (there are other plausible explanations). Instead, I just want to point out that the logic doesn’t quite work.

“It might be true that the right-wing shift by left parties caused this realignment. But it doesn’t mean that, if they shift back left, they can undo it,” says Sophie Hill, a Harvard PhD student who studies the politics of redistribution. “That assumption of symmetry we make is never very plausible.”

Decades of politics centering identity issues like race and partisanship can’t be reversed by a socialist politician bursting onto the scene. We saw this not only in the United States, but also in Britain’s 2019 election. Jeremy Corbyn, an avowed socialist well to Sanders’s left, worked as hard as he could to win back Labour’s traditional base: white working-class voters.

Corbyn’s policies actually polled decently well, but it wasn’t enough to overcome the politics of xenophobia and nationalist grievance that powered the Brexit vote. Identity trumped class, leading to the worst Labour election result in nearly 100 years — and a crushing defeat, in particular, among its industrial base.

“In seats with high shares of people in low-skilled jobs, the Conservative vote share increased by an average of six percentage points and the Labour share fell by 14 points. In seats with the lowest share of low-skilled jobs, the Tory vote share fell by four points and Labour’s fell by seven,” the UK’s Financial Times wrote in a post-election analysis. “The swing of working class areas from Labour to Conservative had the strongest statistical association of any explored by the FT.”

The problem is a theory of change that assumes the outcome it’s aiming for. The goal of socialist politics is to reactivate the working class as a political force, but a sweeping wave in a national primary or general election is a really tough place to do that. Socialist rhetoric and policy platforms aren’t enough to change the deep logics that guide the way voters think about the world, which centers on identity issues like partisanship, race, and immigration.

You can see this problem at work in some of the American data on white working class ideology. A new survey of all white voters by YouGov, on behalf of Data for Progress, asked voters a battery of questions about their view of government and economic policy. Whites who fit the Sanders 2016 coalition profile — non-college, rural, low-income — were consistently less likely to express support for social democratic ideas.

For example, YouGov’s pollsters asked respondents whether government had gotten bigger because “the problems we face have become bigger” or government had “has gotten involved in things that people should do for themselves.” College-educated whites picked the former over the latter by a 53-47 margin, while non-college whites said the opposite by a sizable 41-59 margin.

Similarly, voters were asked what they believed was closer to their views: “the less government, the better” or “there are more things that government should be doing.” By a 58-42 margin, rural voters opted for the former over the latter.

The YouGov data most likely reflects the fact that a significant chunk of rural and non-college whites are, in the Trump era, Republican voters. Which is the point: partisan identification overrides and swamps class identity, causing them to think about the world less as members of a class who could benefit from state intervention and more as members of a party that’s generally skeptical of the welfare state.

That’s not to say it’s impossible to imagine the left breaking the current partisan system and winning back the white working class in the long run. There are concrete policy changes in the United States, like automatic voter registration or strengthening unions by repealing right-to-work laws, that might help to increase young voter turnout and help bring the working class “home.” But these are initiatives that can only be enacted after winning elections, not before.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19888851/GettyImages_1211039033.jpg) Scott Olson/Getty Images

Scott Olson/Getty ImagesIn the short run, that means working with the electorate as it actually exists rather than the one you eventually hope to create. The YouGov/Data for Progress poll found surprisingly high levels of support for certain progressive priorities and policies like a wealth tax among suburban whites, who had in the past favored Republicans. This suggests that progressives need to figure out a way to galvanize this group for their candidates rather than try to build a 20th-century-style working class movement from scratch.

“Large shares of suburban whites agree the government should be bigger and almost all support at least a ‘moderate’ amount of regulation,” John Ray, a senior political analyst at YouGov, tells me. “Both sides need [suburban whites] to win, both sides have a chance to win them, and both sides will be fighting tooth and nail for them into November and beyond.”

Political campaigning and the politics of mass electoral movements can be intoxicating. But it seems to have blinded the left as to how weak their structural position in American politics actually is — and how they’ll have to work within existing institutions and demographic cleavages, rather assuming a working class “political revolution,” to have any prospect of wielding power.

Author: Zack Beauchamp

Read More