The news is likely making you feel like garbage. Here’s why.

This morning I woke up feeling like I ran a marathon, when in reality I spent most of yesterday evening slowly finishing an entire grandma pizza and a bottle of wine. It’s not the carbs or the alcohol making me feel gross today, though (or at least not entirely). It was the fact that last night was absolutely exhausting.

The best way to describe the particular feeling of election night was whiplash: Thanks to obsessive polling, constant cable news commentary, and the horrible return of “the needle,” every few minutes it felt like the entire mood of the race was shifting, despite the fact we’ve been told for weeks that this year’s count would likely take longer than usual. Liberals would rejoice on Twitter one moment and despair the next, and vice versa. It was — and remains! — terrible, no matter who you’re rooting for. As Vulture succinctly noted, “Watching CNN on Election Night Felt Like Being Dipped in Boiling Oil.”

Why does this steady and unceasing drip of seemingly contradictory information feel so uniquely awful? The short answer: Human beings hate uncertainty. For the long answer, I called Dr. Kevin Antshel, director of clinical training in the psychology department at Syracuse University, who explained that as life has grown relatively more stable over the course of history, people crave that stability even more. Now, with the option to seek out unlimited sources of news at all hours of the day, those of us who crave information are stuck in one giant doomscroll. Luckily, Antshel also had some tips on how to look away.

What are your thoughts about how the election results have been messaged to people?

There’s a tremendous amount of uncertainty and it’s going to impact some people in a negative way. Not everybody, but particularly those that are intolerant to uncertainty.

From an evolutionary perspective, it really has made sense for the human race to seek out things we’re confident about because it helps to keep us alive. Things that we’re uncertain about, we tend to avoid, but over time that intolerance of uncertainty has continued, even though our life circumstances have changed, and we don’t have to be so wary of uncertainty. With that predictability, people continue to have increases in intolerance of uncertainty.

So even though our lives are more stable, that just makes us desire stability even more?

Yes, absolutely. We’ve become accustomed to it. This is something we’ve really grown to like.

Why does uncertainty make many of us feel so terrible?

Intolerance of uncertainty is associated with depression and anxiety, and for those folks, uncertainties are unacceptable. The consequences of intolerance to uncertainty really can take any number of shapes; the most common one is probably experiential avoidance.

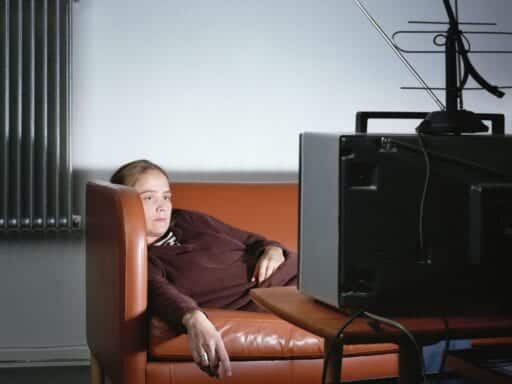

What people do is engage in a lot of binge-watching TV and other things as an attempt to resolve this uncertainty; they need to have closure, they need to know now what’s going to happen in the election, or they need to know now when a vaccine is going to be available. So unfortunately, the intolerance of uncertainty [combined with] them attempting to avoid the uncertainty actually makes things worse, because they’re exposing themselves to more of this information, which will feed back into the uncertainty.

I don’t know if you’ve heard the term doomscrolling, but this sounds a lot like that. Why is that so bad for us?

As a psychologist, I usually like to look on the bright side, but I can honestly say there’s really nothing positive. I think the doomscrolling is probably related to the novelty, that this is something new, something unexpected. We’re interested in continuing to gain more information, and that leads us to exposing ourselves to lots of this negative information.

There’s always going to be a slow drip of news no matter what’s happening in the world, but the stakes are much higher, obviously, when we’re dealing with a pandemic and an election. What does that end up doing to us on a cultural level?

Chronic doubt. I teach at an undergraduate university, and a number of undergraduates are not sure about what news they can and can’t believe. There’s also an overestimation of threat, which is going to lead to increased worrying and people attempting to seek more reassurance. Unfortunately, that makes things worse.

As I’ve already alluded to, there’s a really increasing need for predictability, and I think what we’re doing as a society, as we’re attempting to make things more predictable, we are really having a cognitive reaction to ambiguity. We’re becoming more rigid, trying to dichotomize things as good or bad or black or white types of solutions. As a society, we’re being trained to rigidly dichotomize things into, “This is right, this is wrong.” That isn’t a good way to resolve uncertainty.

Can we alleviate some of that anxiety by giving up control and embracing that gray area?

I think that’s a wonderful solution. We do this a lot in our interventions for anxiety disorders. I’m not sure if you’re familiar with acceptance and commitment therapy, but it’s closely related to mindfulness. Mindfulness is observing things from a nonjudgmental stance. Instead of trying to resolve this uncertainty, you would say, “This is uncertainty,” and not attach a judgment to it. Leaning into the uncertainty is the way out, because the more you protest or attempt to resolve this uncertainty — the things that people are trying — it’s actually making it worse.

Last night, cable news networks and “the needle” made it feel like the polls were going one way one minute and another the next, despite the unique circumstances of the counts this year. What’s the problem with that kind of framing?

The reason they’re framing it that way is because they’re attempting to keep viewers engaged. Uncertainty is like a train accident that we can’t avert our eyes from because we’re attempting to gain team control. I turned it off, honestly. From what I’ve read about the back and forth, I don’t think that is going to sit well with people who are predisposed to intolerance of uncertainty. In a paradoxical way, I suspect those were the people who stayed the most glued to the TV.

What are some things that we can do on an individual level to increase our tolerance of uncertainty? My jaw has been clenched for like a month straight.

The antidote to uncertainties is, obviously, certainty. So where does uncertainty live? Uncertainty lives in the future. So I think the more that people are thinking about the future — and I don’t mean 10 or 20 years from now, I mean tomorrow or Friday — it’s actually quite hard to focus on today and to keep yourself grounded in the present. The more you think about the future, the more anxious you’re going to get, and the more you’re going to attempt to avoid the anxiety, which is going to lead to all the other things that I’ve referred to.

One of the best things you can do for certainty is have routines. I’ve had a number of my friends say, “I’m not sure if I’m working at home or living at work.” The routines are broken down, and the things that helped our society to have predictability have broken down. So I encourage folks to really make things as routine as possible, to pay attention to sleep, pay attention to diet, pay attention to physical activity — all the things that we know help with reducing stress. If you come into this with elevated level of stress, uncertainty is going to be the gasoline on that fire.

Anything else you want to add?

Turn off the TV.

Author: Rebecca Jennings

Read More